Illustration: Asaf Hanuka

it’s not widely enough appreciated just how hard this economic crisis is going to be on the old. Why? Because unlike the working population, they are often, well, no longer working. And while the laid off are, of course, in deep trouble, those who hold on to their jobs in a depression do fairly well. Their costs (like gasoline) tend to fall more than their incomes. That means real wages rise, as indeed they have, thus far, in this crisis.

But the elderly tend to live off their assets. These include homes, already down by nearly 30 percent nationally and much more in certain parts of the country. They include corporate stocks, often in 401(k) accounts, down by 50 percent or so, so far. They include cash and bonds, which earn the interest rate—enough said. And there’s not much else. A sharp decline in any one of these would be a problem; the simultaneous crash of all three is a calamity for the ages—and the aged.

And not just for them. Last December Mark Zandi, the chief economist and cofounder of Moody’s Economy.com, estimated that spending power for the elderly as a group would fall $200 billion as a result of their losses just up to that point. Given the usual multipliers, that’s enough to knock perhaps two percentage points off total production and to cost millions of jobs. Losses to the old are not made up by gains elsewhere; the people they previously employed or gave business to are put at risk of losing their jobs too.

But the elderly do have a backstop: Social Security and Medicare. Thanks to these two programs (and to Medicaid, which covers long-term care at the end of life for many people), no matter how badly things go in the private sector, most of the aged will not become destitute. As things stood before the crisis, 22 percent of the elderly relied solely on Social Security, and while their living standard was very modest, most were still above the poverty line. For the most part we will not return to the days when the corpses of old paupers were collected from the city streets.

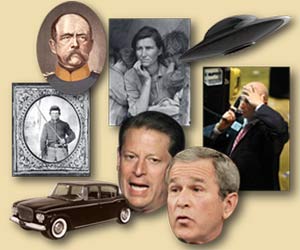

But imagine where we’d be if Congress had accepted George W. Bush’s privatization plan. The part of Social Security siphoned off to private accounts would have suffered the market’s losses, and recipients would be forced to live off a basic benefit substantially lower than Social Security presently is. At the lower end, Social Security is already not much. (The 2009 median is only $13,950 a year.) Cut it back enough and life expectancies could start to fall.

That’s no joke. In Russia, male life expectancy following the industrial collapse in 1991 dropped from 65 to 58 years, mostly due to depression, alcoholism, violence, themselves due to the destruction of savings through hyperinflation and the lack of public health care. Don’t think it can’t happen here. It would, if Social Security and Medicare didn’t stand in the way.

Given these conditions, it’s quite amazing that we are still hearing private-equity mogul Peter G. Peterson, his employee David Walker (formerly the US comptroller general), and other Tory stalwarts caterwauling about the viability of Social Security and the risk that Medicare will somehow bankrupt the United States. The remedy, for those who accept this view, is “reform”—meaning cuts to Social Security benefits slowly phased in, and more rapid cuts in Medicare, probably by restricting the services for which doctors could expect reimbursements.

The caterwaulers’ argument is based on something called “intergenerational accounting”: comparing Social Security and Medicare’s projected outlays to payroll-tax (a.k.a. fica) revenues over very long periods. The resulting “shortfalls,” amounting to tens of trillions of dollars, are scary looking and headline grabbing. They lure the credulous into imagining that the country is struggling under an appalling burden, and that as a result the government is certain to do very bad things, like raise interest rates, or put us under the control of the communists in Beijing. As for raising interest rates or going bankrupt: The market has the same information as Peterson and Walker. You can check the long-term rate on Treasury bonds, if you’re worried—for what it’s worth, the financial markets plainly are not.

So, sure, Medicare’s balance sheet reflects the overall problem of runaway health care costs—problems we need to fix whether or not social insurance is part of the equation. But the preoccupation with Social Security and Medicare is dangerous to the prospects for economic recovery. Why? Because it raises anxiety among workers—especially the young—who’ve been told repeatedly that these programs will not be there for them. The rational individual response, in that case, is to save more and spend less. I don’t think this effect is very large, right now, but it is a risk. There are cases in the world (notably China) of distressed populations oversaving obsessively to try to provide for security that could be provided much more cheaply by social insurance.

Talk about the supposed need to cut back on Social Security and Medicare also gets in the way of the discussion we should be having on how to use these programs to get us out of the hole we’re in. Each could be a powerful and useful weapon against the crisis. To wit:

- A permanent increase in Social Security benefits would help offset the losses that the elderly population is suffering on its housing, equity investments, and cash holdings. A 30 percent increase in benefits would not repair individual losses, but it would help keep the elderly, as a group, out of poverty, and relieve severe difficulties in many specific cases. As a bonus, there’s a stimulative effect: Middle-aged folks won’t need to put their diminished resources toward caring for their parents, freeing them to make other investments.

- A one-year, renewable payroll-tax holiday would greatly ease the financial strain on America’s working families, giving them roughly an 8.3 percent pay increase and their employers a comparable reduction in the cost of keeping them on the job. Many mortgages would be paid, and many cars purchased, that would otherwise default or go unsold.

- A reduction in the age of eligibility for Medicare to (say) 55 would be a powerful response to the industrial crisis, permitting many older workers who would like to retire but cannot afford to lose health insurance to do so. It would also relieve private industry of part of its health care burden, while not abolishing employer-based insurance or infringing on existing health care benefits of the prime-age workforce.

These three measures are among the most promising tools policymakers have right now. Congress should be prepared to use them if and when it becomes clear that the present policies are insufficient.

Indeed, even if there were no crisis, the historical linkage between benefits paid out and payroll-tax revenues received should be broken. Social Security and Medicare should be treated as the bonded obligations of the government—like net interest—thus making explicit what is obvious, which is that these programs cannot go “bankrupt” any more than the government itself can. And, lest anyone forget, in more than two centuries of continuous operations, and despite crises far worse than this one, the government has never gone bankrupt.