Jared Bernstein takes on one of my favorite hobbyhorses today: the supposed anger of the American electorate. He concludes that, yes, the economy is in pretty decent shape, but:

For every statistic you can find, I can find one that tells if not a different story, a more nuanced one. Yes, the jobless rate is 5 percent, but the underemployment rate, juiced by 6 million part-timers who want full-time jobs, is a considerably less comfortable 9.7 percent. No question, wages are rising, but the major source of real income growth over the past year has been low inflation. Paychecks aren’t growing so fast as much as prices have been growing a lot more slowly.

….So I think I get why some people are unsatisfied with the economy and beyond. Growth hasn’t reached all corners by a long shot, and policymakers have too often been at best unresponsive to that reality and at worst, just plain awful.

I think this misses the point. Sure, no economy is perfect, certainly not this one. So of course you can always find plenty of things to kvetch about.

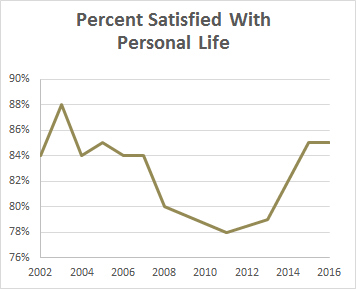

But why bother when you can just ask people directly how they’re doing? If you do that, you’ll find that their responses are fairly positive: better than in 2009, worse than in 1999. But overall, pretty unremarkable. No matter how many economic statistics you haul out, the bottom line remains the same: on average, Americans don’t say they’re  any more or less happy about the economy than they usually are. So unless they’re lying, the economy just isn’t a big factor in the anger driving this year’s election.

any more or less happy about the economy than they usually are. So unless they’re lying, the economy just isn’t a big factor in the anger driving this year’s election.

So why are voters so angry? That’s a good question, except for one thing: it assumes that voters are angry in the first place. It’s true that if you go out and talk to people, you can find plenty of angry folks. That’s always the case, but it’s completely meaningless. The only interesting question is: Are Americans angrier than usual? It sure doesn’t look like it, does it?

You can take a look at every poll you want, and what you’ll find is that, generally speaking, Americans just aren’t unusually unhappy or unusually angry right now. They just aren’t. There’s virtually no serious data to suggest otherwise.

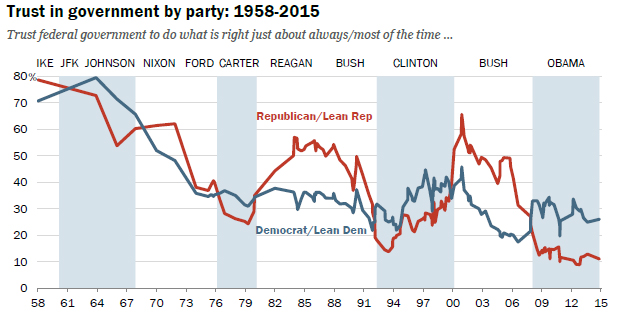

Except for one thing: Americans are pissed at the government. Especially Republicans. Among Democrats, trust in government since 1980 has bounced around a bit depending on who’s president, but it’s generally in the range of 20-40 percent. Among Republicans it’s more like a range of 10-60 percent:

Right now, trust in government is around 30 percent among Democrats, which is pretty average. But among Republicans it’s at a blood-boiling 10 percent—and has been for the past eight years. Obama’s presidency—presumably egged on by Fox News etc.—has sent them into an absolute rage about the government.

So if you want to know what’s going on, that’s it. In general, the economy is OK. Americans are fairly satisfied with their lives. Consumer sentiment is fine. Right track/wrong track has been pretty steady. Only one thing has really changed: The Republican base is furious about the Obama presidency.

That’s it. That’s your anger right there. That and nothing more.

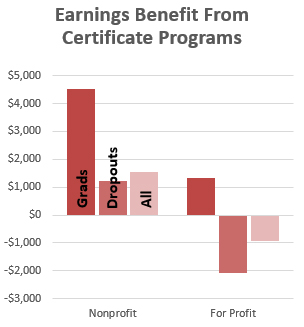

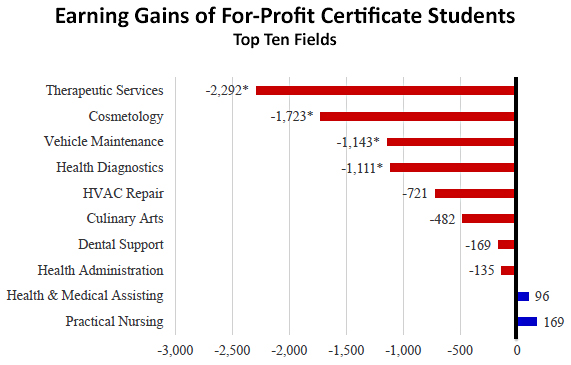

Those newly unsealed documents in the Trump University case don’t paint a pretty picture of

Those newly unsealed documents in the Trump University case don’t paint a pretty picture of  rip-off, but check out the chart on the right. On average, counting both grads and dropouts,

rip-off, but check out the chart on the right. On average, counting both grads and dropouts,

benefit from a gendered double standard where men are automatically presumed qualified for public office and women are not.

benefit from a gendered double standard where men are automatically presumed qualified for public office and women are not.

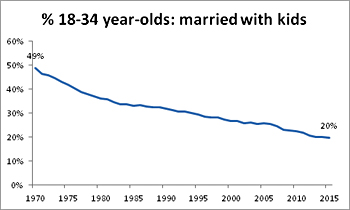

Alongside recent swings in the housing and job markets, there have been profound long-term demographic shifts that are related to young adults’ living arrangements….An especially important trend is that people are waiting longer today than in the past to get married and have kids — so the share of 18-34 year-olds who are married with kids has plummeted from 49% in 1970 to 36% in 1980, 32% in 1990, 27% in 2000, 22% in 2010, and just 20% in 2015. Unsurprisingly, married young adults and those with children are far less likely to live with their parents than single or childless young adults.

Alongside recent swings in the housing and job markets, there have been profound long-term demographic shifts that are related to young adults’ living arrangements….An especially important trend is that people are waiting longer today than in the past to get married and have kids — so the share of 18-34 year-olds who are married with kids has plummeted from 49% in 1970 to 36% in 1980, 32% in 1990, 27% in 2000, 22% in 2010, and just 20% in 2015. Unsurprisingly, married young adults and those with children are far less likely to live with their parents than single or childless young adults.

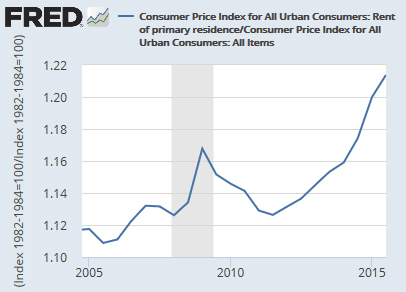

whammy affecting millennials: (1) their incomes dropped during the Great Recession and still haven’t fully recovered, (2) college grads are saddled with more debt than previous generations, and (3) the real cost of housing has increased nearly 10 percent over the past decade. Put all this together, and the average millennial today has less disposable income but faces higher rent than previous generations. This is a real problem, and it would be surprising indeed if it literally had no effect at all on the likelihood of 20-ish millennials living at home longer than they used to.

whammy affecting millennials: (1) their incomes dropped during the Great Recession and still haven’t fully recovered, (2) college grads are saddled with more debt than previous generations, and (3) the real cost of housing has increased nearly 10 percent over the past decade. Put all this together, and the average millennial today has less disposable income but faces higher rent than previous generations. This is a real problem, and it would be surprising indeed if it literally had no effect at all on the likelihood of 20-ish millennials living at home longer than they used to.