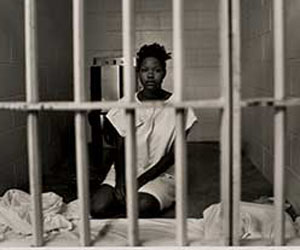

Photo via <a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prison_Punishment.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>

The US Supreme Court today barred a practice that is already considered unconscionable in the rest of the world. In a 6-3 decision, the Court ruled that sentencing juveniles to life without the possibility of parole for any crime short of murder violates the Constitution’s 8th Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

In Graham v. Florida, the Supreme Court ordered a parole hearing for Terence Graham, who was sentenced to LWOP for crimes committed when he was 17. Graham was convicted of taking part in an armed robbery and home invasion in which no one was killed. The Court also struck down laws in 37 states that allow sentences of LWOP terms for non-homicides by juveniles. Currently, 129 inmates nationwide are serving such terms; 77 of them are in Florida.

According to the Los Angeles Times, “Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, speaking for the court, said a life prison term with no chance for parole is too extreme for a juvenile criminal whose offenses involve robbery or assault. He also noted that prior to today, ‘The United States is the only nation that imposes life without parole sentences on juvenile non-homicide offenders.’ Kennedy said these young criminals are not entitled to a ‘guarantee’ of eventual release, but they do deserve ‘some realistic opportunity to obtain release’ if they can show they are no longer a danger to the community.

The issue of juvenile LWOP is closely tied to solitary confinement, since as we have written previously on Solitary Watch, a large number of young offenders end up in long-term isolation in adult prisons, either because they are considered disciplinary problems, because they feel compelled to join prison gangs, or because they have to be isolated from adult offenders “for their own protection.”

The ruling will help a small group of prisoners, including Ian Manuel, who was given LWOP for a botched robbery attempt in Tampa, in which a woman suffered a non-fatal gunshot wound. According to one of several pieces on his case by Meg Laughlin in the St. Petersburg Times, when Ian Manuel “arrived at the prison processing center in Central Florida [in 1991], he was so small no one could find a prison uniform to fit him…Someone cut 6 inches off the boy’s pant legs so he would have something to wear.” An assistant warden told Laughlin that Manuel was “scared of everything and acting like a tough guy as a defense mechanism…He didn’t stand a chance in an adult prison.” Within months, Manuel was placed in solitary, where he has remained ever since.

Laughlin wrote a new piece about Manuel last week, as he awaited the Supreme Court decision that would determine how he spends the rest of his life:

Manuel, now 33, has spent nearly all of his time in prison in solitary confinement, caught in an endless cycle of misbehavior and punishment. As Florida’s longest-serving inmate in solitary, he has no work skills, no formal education and so much psychological damage that he once set himself on fire. People always assumed—whether he killed himself or died of old age—that Ian Manuel’s death would happen behind bars. Not anymore. He may walk out of prison in the next year.

Confronted with the possibility of his release, prison officials, who had kept Manuel as far away from civilization as they could, are scrambling to prepare him for life outside. And his attorneys are laying out a plan that will attempt to protect Manuel from a world he fears will present him with more choices than he can handle. “The uncertainty out there makes me nervous,” he says, “but I’m determined to succeed.”

When he began his sentence in a tough adult prison at age 14, he was small and defensive. Afraid to appear vulnerable, he got into trouble immediately. He’d veer into the grass instead of walking on the path in the prison yard. When guards yelled at him, he’d yell back. When they came at him, he’d make obscene gestures. In less than a year, he was in solitary.

From there, the disciplinary infractions multiplied — for storing aspirin, for sticking his hand through the food flap, for standing at his cell door, for masturbating and for cursing. He would go six months at a time lying on his bed in what he called “a state of hibernation” to stay out of trouble. But it didn’t matter. Each infraction added months and after a while the hole was so deep he couldn’t get out.

Recently, he received a visit from someone not on his legal team. It was his first in 15 years. Leaning forward toward the glass separating him from his visitor, he tried to explain what kept him there: “I’d tell myself to keep quiet and behave. But I was so desperate I couldn’t control my impulses.”

The result has been a life stripped of life. No programs or education. No visitors, phone calls or human touch. No books, magazines, TV or radio. No talking. No standing at the cell door and looking out. Three 10-minute showers a week. Meals pushed through a flap in the door. Enforced idleness in a concrete box, year after year.

According to corrections reports, Manuel became a cutter at 17 — slicing his arms with tiny fragments of glass and metal and watching the blood flow. “It gave me relief from the intolerable numbness,” he said.

At different times over the years he went on a hunger strike, overdosed on pills and even set himself on fire with a smuggled match and newspaper he tied to his legs with strips of bedsheet. The result wasn’t therapy, it was harsher solitary: No clothes, no mattress, no sheet. A bare cell with 24-hour lights, 60-degree temperatures and no view out. “It’s a miracle I haven’t totally lost my mind,” he said.

In 2007, he testified by video from solitary confinement at a hearing before Jacksonville federal judge Henry Adams. Manuel described a life of “complete hopelessness.” When he finished talking about trying to kill himself “to end the pain,” Adams called a recess because Manuel’s circumstances so upset him he had to leave the courtroom.

University of California psychologist Craig Haney evaluated solitary confinement at three prisons where Manuel has been held, as part of a case filed by a group of inmates. “Glaringly inhumane,” wrote Haney in his report, citing “harsh treatment, deprived conditions and excessive punitiveness.”

“Ian learned to live under extraordinary control and deprivation,” Haney said recently. “He can’t undo the effects of almost 20 years on his own. He’s facing enormous psychological challenges if he’s released.”

Keep in mind, however, that the Supreme Courts decision affects on a fraction of the inmates serving life without parole for crime committed as juveniles. These number more than 2,500 in all, victims of an explosion in adult sentencing of children in the final decades of the 20th century. The Heritage Foundation marked the Supreme Court’s decision today in a blog post titled “Court Upholds Life Without Parole for Juvenile Killers.” Any child convicted of a homicide can still be sentenced to die in prison. This includes the estimated 26 percent serving LWOP “for felony or ‘accomplice’ murder, in which the juvenile was not the person who killed the victim,” according to a report by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

Research by the Equal Justice Initiative, which issued the 2007 report Cruel and Unusual: Sentencing 13- and 14-Year-Old Children to Die in Prison, found “73 cases where children 13 and 14 years of age have been condemned to death in prison,” nearly two-thirds of them children of color. In most of the cases, “the propriety and constitutionality of their extreme sentences have never been reviewed” because the children don’t have lawyers to mount such challenges. Most of the sentences were mandatory, and “the court could not give any consideration to the child’s age or life history.” Even among homicides, many were “offenses where older teenagers or adults were involved and primarily responsible.”

Finally, as Sara Mayeux points out on her Prison Law Blog, being eligible for parole by no means guarantees that these inmates will ever actually see the light of day: “[I]nsofar as juveniles have now won a right to a parole hearing,” Mayeux writes, “we might question how meaningful of a right that really is (notwithstanding the “some meaningful opportunity” language [in Kennedy’s opinion]) given that in many states, parole hearings have become a sort of charade in which the prisoner can never actually win release, because the parole board routinely denies parole eligbility based solely upon the facts of the underlying crime, which is the one thing that the prisoner, of course, can never change.”

In other words, for thousands of child offenders, the Supreme Court’s decision today offers no hope.

This post also appears on Solitary Watch.