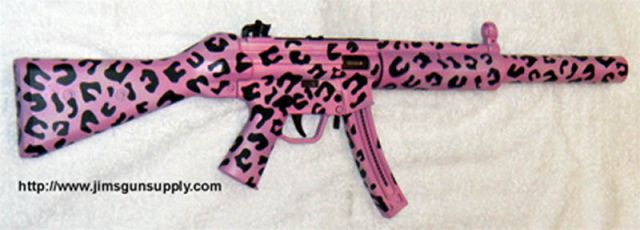

A week ago I traveled down to Compton, Calif. to report on a community fight there over the future of a public school. (Stay tuned for more on that front.) As I waited to meet with parents in McKinley Elementary’s PTA room, Compton School Police Officer Lorenzo Gray came in and pulled out a thick, black binder filled with pictures of colorful guns—pink guns, yellow guns, guns with American flags, guns with white bunnies on them.

A week ago I traveled down to Compton, Calif. to report on a community fight there over the future of a public school. (Stay tuned for more on that front.) As I waited to meet with parents in McKinley Elementary’s PTA room, Compton School Police Officer Lorenzo Gray came in and pulled out a thick, black binder filled with pictures of colorful guns—pink guns, yellow guns, guns with American flags, guns with white bunnies on them.

“Is this gun real or fake?” he asked six Latina mothers at the PTA room. “Fake,” the six mothers responded after they consulted with each other.

After 20 images, the officer then passed a heavy, gray, metal gun around the room. I am actually used to holding real guns—my father and I used to shoot pinecones and bottles during our country summer vacations when I was growing up in Latvia—so I was curious to see how an American handgun compared to the Soviet ones my father used to own. The weight was similar, it was cold to the touch, and it felt rough around the edges. There was a small sign that said, “Made in Japan,” and it had serial numbers on it. “Fake or real?” the officer asked me, as I turned to him. “Don’t point it at me!” he laughed. Turns out the one I was holding was a toy, and those pink and patterned ones (like the ones shown here) were real.

Until Compton, I’d never seen pink or yellow guns. Turns out they’ve been on the rise in the last five years or so, Lorenzo said. “It’s become impossible to tell a real gun from a fake one apart,” Lorenzo warned the shocked mothers in the room. “Don’t buy any guns for your kids. There are too many accidents where kids think they are using a toy and shoot somebody.” He added that it also makes the job of the police officers really difficult: they might mistake a fake toy gun for a real one, and might shoot accidentaly, in self-defense, Lorenzo explianed.

As I searched online, I found places that will let you buy kits to color your own guns, sort of like deadly Easter eggs, or send them in for a custom job. Mayor Bloomberg was the first official in the country to ban painted guns, but it seems that merely a few other counties followed the suit. Federal provisions only require toy-gun makers to put blaze-orange caps over the barrels to distinguish toys from the real guns.

In Compton, the toy guns that look real used to come mostly from ice cream trucks that cruised the sunny streets until the city banned them completely, Erika Herrera, the PTA representative at McKinley, told me. But those ice cream trucks still show up sometimes after dark, she said.

In Compton, the toy guns that look real used to come mostly from ice cream trucks that cruised the sunny streets until the city banned them completely, Erika Herrera, the PTA representative at McKinley, told me. But those ice cream trucks still show up sometimes after dark, she said.

Some researchers link the increases of youth homicides since the ’80s to increasing access to guns due to lax regulation, and decreasing access to jobs in low-income communities, like Compton. Twenty-one teenagers aged 13 to 19 were shot in Compton since 2007. In Santa Monica, only 20 miles away from Compton? That number is 0. While it’s hard to reduce poverty and increase jobs in an economic downturn, the government does have control over making policy. But until gun control laws around painted guns, toys that look like guns, and real guns improve, Officer Lorenzo has his work cut out for him.