<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/therefore/3981810961/sizes/z/in/photostream/">Dean Terry</a>/Flickr

On Wednesday the FBI announced that it had arrested Rezwan Ferdaus, a Northeastern University graduate in physics, for allegedly plotting to fly model planes packed with explosives into government buildings in Washington, DC, and elsewhere. As with previous sting operations, the actual plot, reliant on equipment provided by undercover FBI agents, was never going to take place. Unlike previous sting operations, the FBI got the target to outline the entire thing in writing.

“It seems like the FBI intentionally trying to ensure the entrapment defense couldn’t be mounted,” says Karen Greenberg of the Fordham Center on National Security.

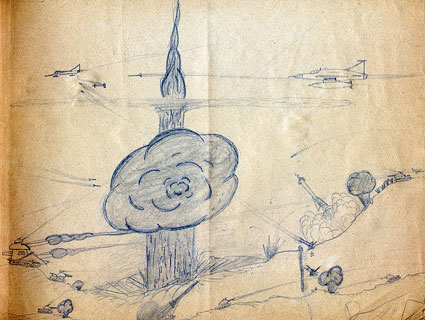

According to the criminal complaint, Ferdaus handed the FBI agents a thumb drive with a plan described as “extremely detailed, well written, and annotated with numerous pictures.” Ferdaus doesn’t appear to have found anything suspicious about two supposed Al Qaeda operatives asking for what sounds, essentially, like a grant proposal.

As Trevor Aaronson reported in the September/October issue of Mother Jones, the FBI has relied increasingly on these kinds of sting operations as they try to shift focus from “professional” terrorists to “lone wolf” types who haven’t received any kind of formal training. The government has come under criticism from civil liberties advocates who say that the government is using agent provocateurs to manufacture terror plots involving people who might not otherwise have committed crimes.

Ferdaus’ plan, though detailed, wasn’t necessarily functional. He seems to have had trouble calculating how much explosive the planes could actually carry, and Talking Points Memo‘s Ryan J. Reilly spoke to an explosive expert who said that “the model planes would have to fly in though a window to do any real damage.”

That said, Ferdaus’ decision to write everything down may make arguing an entrapment defense even more difficult than usual. South Texas University law professor Dru Stevenson says that it’s not enough for defense attorneys to argue that Ferdaus couldn’t have executed the plot without FBI assets posing as accomplices—he has to show that he wouldn’t have done anything like this in the first place without the FBI’s encouragement.

“The jury will have trouble believing that someone who writes out the entire sinister plan is harboring doubts, dragging his feet, or hesitating,” Stevenson says. “The more premeditated the crime looks, the more willful it appears to be. There is no necessary connection—we know logically that people plan things they end up never doing…Nevertheless, I think the FBI knew that the jury would associate premeditation and planning with a predisposition to do the act.”

The criminal complaint also alleges that Ferdaus turned several mobile phones into detonators for improvised explosive devices, which the undercovers told him were used to kill American soldiers in Iraq. Ferdaus responded that this was “exactly what he wanted,” the kind of statement that will make it difficult for Ferdaus’ attorneys to argue that he wasn’t predisposed to committing this kind of act.

That said, there’s plenty of information that isn’t in the complaint that may turn out to be relevant—such as how Ferdaus came in contact with the FBI cooperating witness in the first place. The complaint states that Ferdaus started looking into “jihad” some time “beginning on or around” 2010, but the witness doesn’t make contact with him until January 2011, and the two undercover agents in March. That leaves unanswered the question of whether or not Ferdaus got serious about executing a plot only after coming into contact with FBI assets. Greenberg refers to that potential scenario as “ideological entrapment.”

“That’s when the government teaches someone the ‘proper’ way of doing jihad,” she explains, “rather than finding someone who is already seeking to commit a crime.”