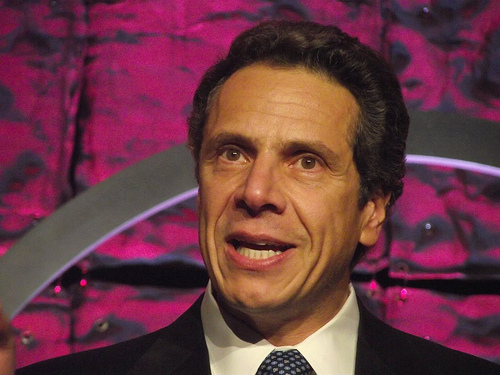

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D).<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/azipaybarah/6288050455/sizes/m/in/photolist-azDUk2-azGysU-azDRy4-azDSoK-azDY4k-azGCud-azGChd-azDW3k-azGDsG-azDUrH-8KeoTd-azDREZ-azDPja-azGuhG-8KeoY1-azDWRv-azGyfu-azGwJu-8KenEA-8Keo2w-8Kep8b-azDUfx-8Keo71-azDSvH-azDR9H-azDRdr-azGweN-azGvVA-azDQWa-azGwpq-azDRjZ-8KenRN-9X35gz-8DaTHX-8De1No-dSQ8Fu-dSQ7Z7-7bnC5B-8Db1We-dSJyf4-8De8tw-9X5VLu-8De8yb-dSQ8BW-8De1DA-8DaTc8-9X5VWd-aDtQH8-86upre-8Ee3xN-8EaPK8/">azipaybarah</a>/Flickr

In June, an anti-corruption bill that included the holy grail of money-in-politics reforms—public financing of elections—died in the New York State Senate. Progressives and election reformers had pinned their hopes on passing a public financing system modeled after New York City’s, a system that helped Bill de Blasio clinch the Democratic mayoral primary. But they weren’t left empty-handed when the bill died: In its place, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) created the Commission to Investigate Public Corruption to get at the root of Albany’s corruption woes and to study the funding of state elections.

Now, it looks like Cuomo’s commission is not all it’s cracked up to be. And the Cuomo administration is partly to blame.

State lawmakers are refusing to turn over the information about their outside income that the corruption commission requested, the New York Times reports. Cuomo’s staff, meanwhile, “has leaned on the commission to limit the scope of its investigations,” according to the Times.

Here’s more from the Times:

The turmoil over the commission began in late August, when it asked members of both houses of the Legislature to release information about their outside income above $20,000. Several weeks later, lawyers for the Legislature refused, saying, “These demands substantially exceed what New York law authorizes.”

The commission’s relationship with the governor’s office has also been freighted. It issued a flurry of subpoenas at the start, but then was slowed by Mr. Cuomo’s office in several instances, according to people familiar with the situation who insisted on anonymity because they feared retribution by the governor.

In one such instance, when the commission began to investigate how a handful of high-end residential developers in New York City won tax breaks from Albany, its staff drafted, and its three co-chairmen approved, a subpoena of the Real Estate Board of New York. But Mr. Cuomo’s office persuaded the commission not to subpoena the board, whose leaders have given generously to Mr. Cuomo’s campaign, and which supported a business coalition, the Committee to Save New York, that ran extensive television advertising promoting his legislative agenda.

A Cuomo spokeswoman told the Times that “ultimately all investigatory decisions are up to the unanimous decision of the co-chairs.” Still, New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman said he’s worried about “interference and micromanagement” at the commission, and good-government groups are increasingly disillusioned over the commission’s trajectory. “New Yorkers are losing patience with the continuing culture of corruption in Albany and the continued indictment of their representatives,” reads a letter from Common Cause New York to Cuomo. “The commission was established to help restore their faith in government, not confirm their cynicism that the system will never change.”