Texas Department of Criminal Justice/AP

On July 27, Texas is scheduled to put Taichin Preyor to death for the 2004 murder of Jami Tackett in San Antonio. Preyor’s guilt was never in much doubt, but according to his petition for clemency, the competence of the lawyers who had represented him should be. The Constitution guarantees the right to a fair trial and effective counsel but, his new lawyers assert, Preyor has received anything but.

“He has never had capable counsel make the best argument available,” says Cate Stetson, one of Preyor’s new court-appointed lawyers who joined the case in May.

During his first trial in 2005, Preyor’s court-appointed lawyers failed to investigate his troubled childhood, which might been a mitigating factor in persuading the jury to forgo capital punishment. Then, during the appeals process, one of the private attorneys hired by Preyor’s mother allegedly had no experience in defending death penalty clients while the other one had been disbarred 17 years before. Preyor’s new lawyers allege that both lawyers defrauded the court.

After these attorneys withdrew from the case, Preyor’s new lawyers filed a petition for clemency to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles. At best, they hope Texas will commute his death sentence. But they are also hoping to persuade the state to grant a reprieve of at least 120 days during which they would be able to present a new case in federal court. They argue that given the poor representation Preyor has received from the time he entered the criminal justice system, his new counsel should be given the opportunity to sufficiently investigate his background so as to finally present his complete case to the courts.

As with so many inmates who end up on death row, 46-year-old Preyor had a tragic childhood. According to the petition, he had been sexually abused repeatedly by an unnamed family member and physically abused by his father and mother. When he was 14 and trying to escape from his mother who was chasing him with a knife, according to the documents in the clemency petition, he jumped out of a window and broke both ankles and one hand.

Drug and alcohol abuse began when he was a teenager, and as an adult he cycled between intoxication and using cocaine to sober up. When he was in such a state, he attempted to burglarize the home of the woman from whom he regularly bought drugs, and then he killed her. Chronic abuse of alcohol and cocaine can result in the impaired judgment and violent behavior that, according to his lawyers, may have played a role in his crime.

Yet, during his first trial, his court-appointed counsel failed to present this information to the jury. Mitigating evidence can sometimes persuade a jury not to choose capital punishment, but in his case, the jury was told “he came from a functional family,” says Stetson.

After he was convicted and sentenced in 2005, Preyor was appointed new counsel for post-conviction proceedings at the state level. But Margaret Mendez, Preyor’s mother, was dissatisfied with his representation and sought private lawyers for the remaining portion of his appeals through the state and federal courts.

In 2007, Mendez’s niece, Melanie White and her husband, found Philip Jefferson, a lawyer based in Los Angeles who had represented White’s husband in a murder trial in the 1980s. He told Mendez that he had worked with Johnnie Cochran and that the famous lead attorney who had represented O.J. Simpson had even given him some cases he was too busy to handle. Jefferson believed Preyor was innocent, he said, but since he was retired he would need another lawyer to assist with the case. His choice was Brandy Estelle, another LA-based lawyer, and their fee was $20,000 to represent Preyor through the appeals process.

There were some problems they did not disclose: Jefferson had been disbarred in 1990 for repeatedly failing to sufficiently represent his clients. And Estelle had no experience representing death row clients. According to the clemency petition, the one name that appears on the court filings is Estelle’s, so she appears to be Preyor’s only lawyer.

“Jefferson and Estelle committed fraud on the court,” Stetson says plainly.

For the next five years, from 2008 to 2013, according to court documents, Mendez shelled out thousands of dollars to the attorneys on top of the original $20,000, which she said included preparation for hearings at the state court and for visits to Preyor in prison.

In her sworn affidavit, Mendez said she was worried Jefferson was spending the money on gambling instead of representing her son. “I could even sometimes hear the slot machines in the background,” she wrote about her phone conversations with the disbarred lawyer.

Meanwhile, according to the petition, Estelle was being paid twice for some of the same work. Once from Preyor’s mother and eventually from the courts. Her first effort to become his court-appointed attorney failed in 2011, when the US District Court for the Western District of Texas denied her motion for appointment saying she “failed to demonstrate she currently possesses sufficient background, knowledge, or experience to enable her to properly represent [Mr. Preyor].” A year-and-a-half later, the Fifth Circuit granted her appointment and she became eligible for compensation from the courts, during the same period of time she was still collecting payments from Mendez.

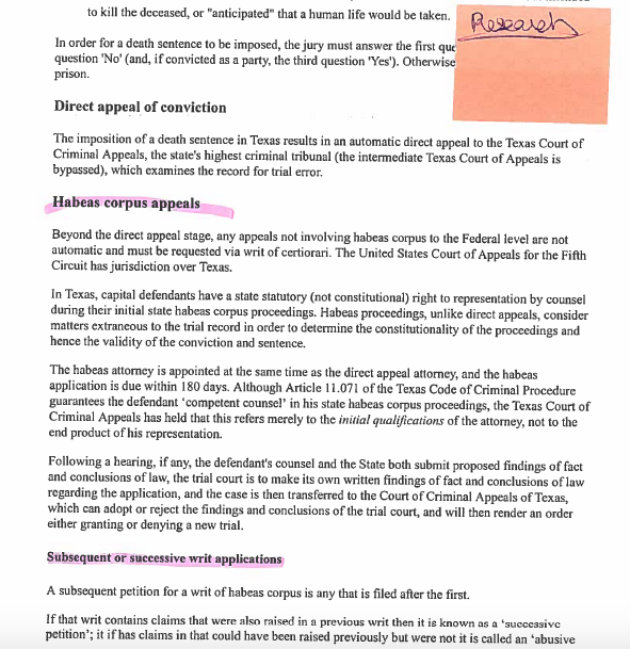

According Preyor’s current lawyer, the work Estelle was receiving double payments for was substandard at best. She appeared to be relying on Wikipedia “to learn the ins and outs of capital work,” Preyor’s lawyers wrote in the clemency petition. Her files included a printed-out page, “Capital punishment in Texas,” with highlighted passages and a sticky note with the word “Research” next to the sections on “Habeas corpus appeals” and “Subsequent or successive writ applications.” The pages were printed in June 2014, after Preyor’s state habeas applications had already been denied.

A portion of the printed out Wikipedia pages from Estelle’s files.

Instead of making an ineffective assistance of trial counsel claim when filing his appeal in federal court, the two lawyers repeatedly filed appeals and petitions that were swiftly denied.

Preyor’s appeal reached the US Supreme Court in 2014, but the high court declined to review the case. Jefferson told Mendez to start an online petition and reach out to then-Attorney General Eric Holder and President Barack Obama. “I may not have a legal education, but these seemed like strange things for an attorney to ask the mother of his client to do,” Mendez said in her affidavit.

Feeling dissatisfied with Estelle’s representation, Preyor reached out to Richard Ellis, a California attorney. In her sworn affidavit, Mendez said that Ellis was unable to represent Preyor. But, in early 2015, he offered some advice and the startling news that Jefferson had been disbarred. Mendez decided to fire both Estelle and Jefferson. After warning Mendez that Preyor would be left without a lawyer, Estelle resigned from the case.

It appears that Estelle is still practicing law in California. She did not respond to a request for comment. Jefferson passed away in December 2015.

Once Estelle was out, the court appointed Hilary Sheard, a Texas-based solo practitioner to represent Preyor in March 2015. In May 2017, Stetson and another lawyer joined the team after Sheard needed to step back for personal reasons.

“One of the most trouble things about this case is the way the timing has shaken out,” Stetson says. Sheard requested a budget to begin working on the case in April 2016, but the budget wasn’t approved until May 2017. Preyor’s second execution date was set in March 2017. This left Preyor’s new counsel with little time to build his case.

In the petition for clemency, Preyor’s lawyers argue that because of his previous lawyers’ misrepresentation, their client was denied the opportunity to advance his claim that he was failed by his trial counsel, who did not present mitigating evidence that might have spared his life.

On Monday, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the US District Court for the Western District of Texas denied Preyor’s applications for a stay of execution.

If Texas executes Preyor on July 27, he will die before the courts can take his whole saga into consideration. “No matter how you feel about the death penalty,” Stetson says, “it’s fundamentally wrong to put a man to death when he was essentially represented by a pair of fraudsters.”