Former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick celebrates after their win against the Los Angeles Rams during an NFL football game Saturday, Dec. 24, 2016, in Los Angeles.Jae C. Hong/AP

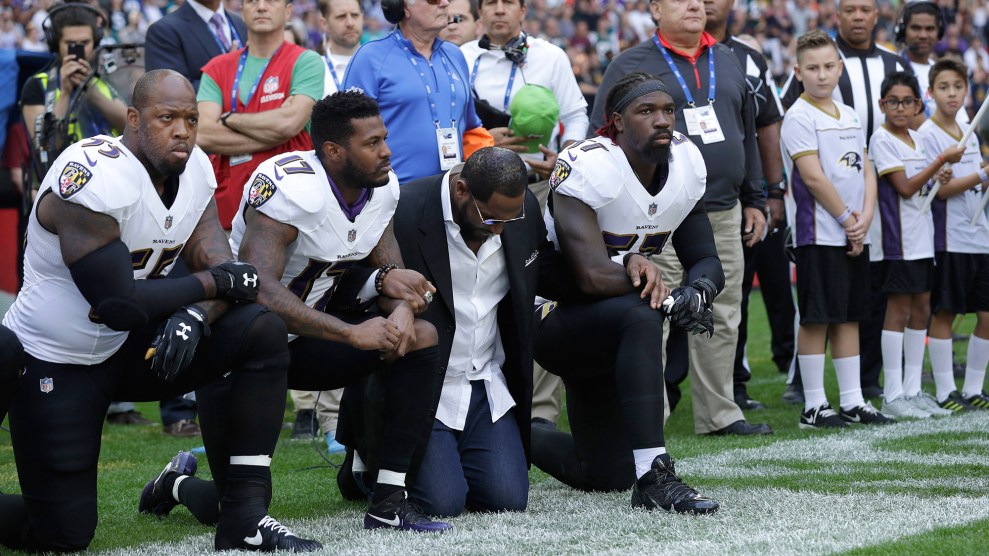

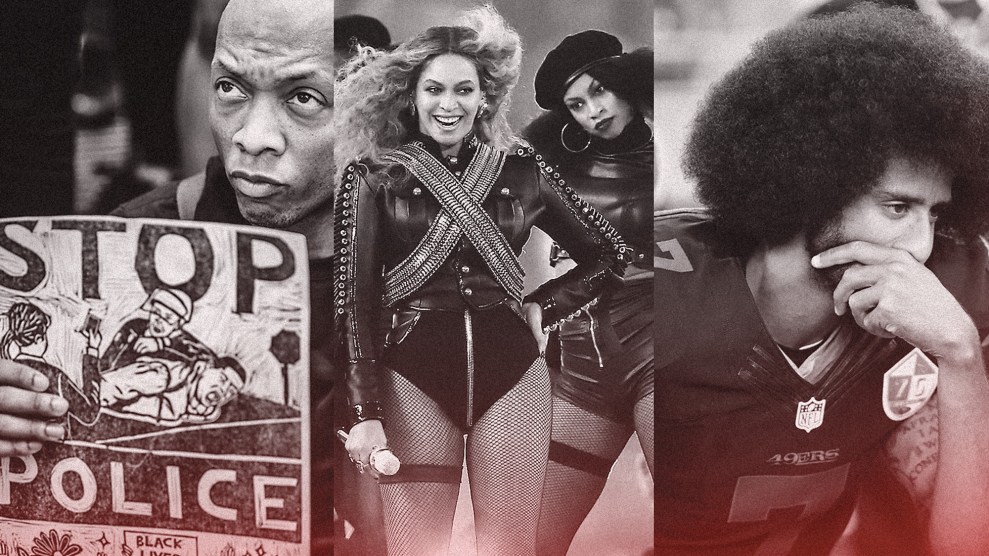

As the NFL season rolls on, so too does the debate over players protesting during the National Anthem and the criticism of former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, the man who set the protests in motion. Things came to a head late last month, when President Donald Trump declared at a rally that NFL owners should fire “[those] son of a bitch” players who kneel for the anthem—a move Trump claims is disrespectful to veterans who, he says, fought to defend the flag.

Among the charges that conservative critics have levied against Kaepernick—who began sitting or kneeling for the anthem last August to protest police violence against black people—is that he’s not doing much off the field to improve the lives of the people he claims to be advocating for. In fact, while Kaepernick’s community activism hasn’t received nearly as much attention as his on-field protests, he’s been plenty active.

Just this week, Kaepernick visited a high school in Harlem to speak to students about social activism. He has also used his social media platforms to help raise money for victims of the various hurricanes. Before that, he sponsored a series of Know Your Rights camps wherein young people, mainly black and Hispanic, learn about their legal rights during interactions with the police. And he’s put up a good chunk of change, too: Since October, through his Colin Kaepernick Foundation, the QB has dispensed $900,000—of a $1 million target—to dozens of nonprofits in Baltimore, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, and elsewhere. Last month, the NFL Players’ Association honored the quarterback with an award for his community outreach.

The grant recipients I spoke with told me Kaepernick’s money has helped them do a lot of good. Take the Los Angeles-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, one of four organizations that received a $25,000 Kaepernick donation in January. The check arrived not long before our freshly minted president began signing executive orders to ramp up immigration enforcement. Executive director Angelica Salas told me the money helped the group revive its rapid-response network (which had been dormant for several years) just in time for one of the administration’s first big sweeps.

On February 6, Immigration and Customs Enforcement launched raids in dozens of communities across six Southern California counties, arresting more than 160 people in five days. CHIRLA and its partners sprang into action. They identified where the raids were happening, tracked down people at detention centers, and sent in lawyers to advise the detainees and ultimately free them. Kaepernick’s contribution covered a “kind of overtime” period for work that the nonprofit hadn’t anticipated. Speed is a crucial factor in such situations, Salas says: “If you’re Mexican, you can be deported in 2 to 3 hours, especially if you’re from Los Angeles.”

During the February raids, Salas told me, CHIRLA and its partners were able to spring 11 people from detention—including one immigrant who was already on a Mexico-bound bus awaiting departure. The network has since gotten about 20 others released, including Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez, a 49-year-old dad whose arrest by ICE agents near his daughter’s school made national headlines after the 11-year-old recorded it on her mother’s phone. Those people “have been able to stay with their families,” Salas said. “They’re still fighting their cases. But they’re here.” (In August, a judge dismissed the deportation order against Avelica-Gonzalez.)

At the time Kaepernick’s money came through, most donors and foundations were just trying to figure out how the new political winds would affect their giving priorities. While “everyone was still deciding what to do,” Salas says, Kaepernick “gave us a new agility to respond.”

In April, Assata’s Daughters, a Chicago group that focuses on the needs of black girls, received $25,000 from Kaepernick—20 percent of its 2017 operating budget. For a fledgling nonprofit—less than three years old, with just one full-time employee—the donation was “huge,” equivalent to a few months of fundraising, says organizer Page May.

The money helped the group, named after former Black Panther Assata Shakur, establish its own office space (it was sharing before), and expand its community programs. Conservative pundits went nuts over the donation, perhaps because one of those programs is a yearlong workshop introducing teens to grassroots organizing strategies through a black feminist lens. (Assata’s Daughters aligns itself with the Black Lives Matter movement, and its volunteers have also organized around police reform.)

Girls taking part in the weekly sessions receive food, a $5 bus pass, and a $10 stipend. One of the goals is simply to keep teenagers out of trouble. “If we want to address [gun] violence, we have to provide young people with a means to make money,” May said. “This is by no means a job, but it’s a little bit.”

That program has expanded from 15 girls to 50, May says, and Assata’s Daughters has also launched one for boys, with 25 participants. In addition, the group runs workshops on coping with violence, including one where kids learned to deal with gunshot and stab wounds before paramedics arrive—skills that two participants actually deployed within days of the workshop, May says. Yet another proposed workshop would teach strategies for de-escalating tense situations. “We want to actually be training up young people to have the tools that they need to deal with some of the things that they’re seeing,” May told me.

I didn’t hear back from the Kapernick Foundation about its giving strategy, but several recipients said they were contacted by Kaepernick’s manager or a foundation rep and asked to write up a brief proposal explaining how they would use the money. Among the grantees listed on the foundation’s website are a Brooklyn group that helps house homeless veterans, a San Fransisco medical clinic that sent staff to support Native American protesters at Standing Rock last year, and the New York City-based Center for Reproductive Rights.

“People are always asking what can celebrities do, and Kaepernick’s model has been to invest directly in the communities that are impacted,” says Adam Jackson, CEO of Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, a Baltimore think tank that addresses black issues. His group received $20,000 from Kaepernick in March. It used the money to pay for its annual policy-and-debate camp, which dozens of students attend free of charge.

“Compared to what it normally takes to get $25,000, he made it extremely simple…He didn’t set up all these hoops that we had to jump through,” May told me. “There’s so much work to be done, and there’s not enough time and there’s not enough money. Kaepernick can’t add more hours to a day, but him throwing money at us allows us to train up that many more young leaders,” she adds. “I think that’s amazing.”