An investigation photo from the Las Vegas hotel suite used by the gunman

In the opening monologue to his late-night TV show on Monday, an emotional Jimmy Kimmel channeled what millions of Americans were thinking about the gun massacre on the Las Vegas Strip that killed at least 58 people and injured nearly 500 others. Kimmel described it as an inexplicable attack by “a very sick person” with an “insane voice in his head.” On the brink of tears, Kimmel said, “We wonder why, even though there’s probably no way to know why a human being would do something like this.”

It was a powerful moment, and yet these widely shared comments from Kimmel also reinforced a misconception that invariably marks the national discourse in the aftermath of indiscriminate mass shootings: that the perpetrator was severely mentally ill, and somehow just “snapped” and went on a killing spree. Law enforcement investigators and journalists have found no record of mental illness for 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, whom police found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. And as with the vast majority of mass shooters, there is substantial evidence showing that Paddock deliberately planned the massacre over a lengthy period of time and then methodically carried it out.

Sunday’s massacre resulted in the highest injury and death toll of any mass shooting in modern US history. As with most of these attacks, untangling motive can be quite complicated. That certainly is the case with Paddock, a former government worker, real estate investor, and itinerant high-stakes gambler whose personal background was a mysteriously blank slate in an initial wave of media reports.

But if determining why a mass shooter struck can be elusive, documenting how he cultivated and carried out his plans—and how insights into those behavioral patterns can help prevent other attacks—is a different story. Calling Paddock a “crazed lunatic full of hate,” as the Las Vegas mayor did, or “a very, very sick individual,” as President Donald Trump did, may offer some catharsis. But it isn’t very helpful for understanding such crimes. (This kind of language can also perpetuate a dangerous stigma against mentally ill people, the vast majority of whom are not violent.)

Here are some of the key details known so far about Paddock’s attack—and, according to law enforcement and behavioral threat assessment experts I’ve spoken with, some of what investigators are scrutinizing to better understand Paddock’s planning and possible motive.

The pathway to violence

Coined by pioneers of the evolving field of threat assessment, the “pathway to violence” refers to a series of escalating behaviors leading to an attack, which can comprise a crucial period of time for possible intervention. Typically this process begins with a deep-seated grievance that turns to motivation, followed by planning and then an act of targeted violence. Though the process varies widely in its circumstances and duration, it precedes virtually all mass shootings.

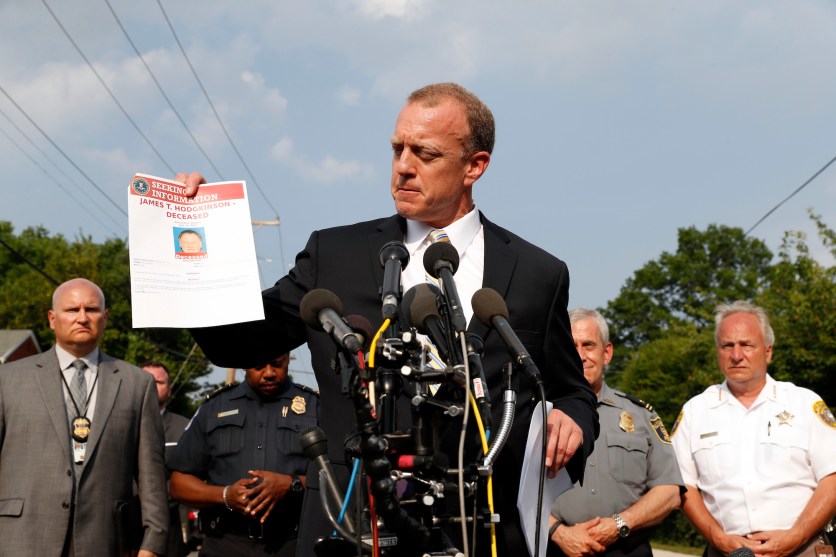

According to police, Paddock arrived at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino three days prior to firing a deluge of bullets from his 32nd floor luxury suite. Over those three days he brought as many as 10 suitcases into the suite, presumably transporting his arsenal of nearly two dozen firearms (mostly assault rifles), ammunition, and accessories, including rifle scopes and tripods. Paddock also installed surveillance cameras inside and outside the room. And he used multiple rifles to conduct the attack from two windows he smashed out with a hammer.

The overall setup was “pretty sophisticated,” as one law enforcement official familiar with the investigation described it to me. Prior to Paddock’s three days at the hotel, this official said, Paddock likely undertook “days or weeks of planning, if not longer.” He may also have considered targeting another music festival the previous weekend. This was not the behavior of a person who had just “snapped.”

Obsession with military-style weapons

Eric Paddock, a brother of the perpetrator who lives in Florida, told reporters that he and his family were “shocked” and “horrified” by the news, and said that Stephen Paddock was “not an avid gun guy.” Clearly he was misinformed. Authorities found a cache of 19 firearms, thousands of rounds of ammunition, and explosives material at Stephen Paddock’s residence in Mesquite, Nevada, about 80 miles from Las Vegas, and additional guns at a home he owned in Reno. Many of the 47 weapons found in total were purchased legally through gun sellers in Nevada, Utah, California, and Texas. Paddock had no military background, but his weapons and tactics—including 12 rifles modified with legal “bump stocks” allowing them to fire at a rate similar to fully automatic weapons—bore hallmarks of a plan designed for killing en masse.

Threat assessment experts have documented many cases where mass shooters cultivated a “pseudocommando” image—attackers who were obsessed with military-style weapons and paraphernalia and aspired to a “warrior mentality.” Whether Paddock ever voiced such interest is unclear, but his preparations and arsenal are an unambiguous measure of it.

Did he signal his intentions?

In the initial aftermath, most media outlets ran with Eric Paddock’s comments that the family, mostly estranged from Stephen, had no inkling that he might commit a violent crime. This is a very familiar trope in mass shootings. What the surprise among family members or neighbors about a perpetrator “snapping” really tends to mean is that “they didn’t know what was going on in his life that led up to it,” says Dr. Russell Palarea, a Washington, DC-based threat assessment professional. In some cases that can include what experts refer to as a “triggering event”—being fired from a job, getting served with a restraining order, or experiencing some other negative life development that can set a potentially dangerous person’s plan into motion.

A thorough investigative process is critical to understanding what happened, says Palarea: “He may have amassed his arsenal with the specific intent of carrying out this devastating attack. Or, he may have been collecting firearms as an aficionado and had no perceived grievance, motivation, or need for notoriety back then. The shift could be more recent. What’s needed is a timeline of his behaviors.”

Forensic research shows that most mass shooters express their intentions before they strike, most often to a third party—a concept known as “leakage.” Data from Paddock’s computers and phone could shed light, as could his girlfriend of several years, Marilou Danley, a 62-year-old native of the Philippines who worked as a casino hostess. Authorities confirmed Danley was overseas when the massacre took place and returned Tuesday night to the United States to speak with investigators. (Some signs began to emerge on Tuesday that Paddock might have been abusive toward Danley; a history of domestic violence is common among mass shooters. Paddock’s two ex-wives have so far declined to talk to the press.)

Psychopathy and suicidal behavior

As investigators seek deeper insight into what could explain the attack, perhaps the most intriguing background on Paddock goes way back: His father was a notorious bank robber once on the FBI’s Most Wanted List, classified by the bureau in 1969 as a dangerous psychopath with suicidal tendencies. (Suicidal behavior is also common among mass shooters—a majority take their own lives, as Paddock did.) According to threat assessment expert Dr. Reid Meloy, research indicates that psychopathic traits can be inherited, and that this is more likely to happen the more severe the trait. That condition “wouldn’t explain specifics of the act,” says Meloy, “but may explain the detachment and cruelty to carry out such an act.”

Evidence may yet emerge as to what was going on inside Paddock’s mind as he plotted his slaughter. It was without a doubt a hideous and evil act, and it was hardly inexplicable.