One day near the end of spring semester, a 22-year-old I’ll call Abbie stood in front of a roomful of cops and recounted what happened after she was raped by another student at her college. Standing very still behind a large podium, she described how she’d driven to campus to file a report in the early morning hours following the assault, hitting 90 miles an hour, half-wishing she would crash. Within days, rumors started circulating about her; a faculty member blamed her rape on her “overcaring personality.” Then she met with Dennis Dougherty, a senior investigator with the Campus Sexual Assault Victims Unit of the New York State Police. Their meeting lasted five hours. She’s memorized the words Dougherty said after she finished telling him her story: “I believe you. I don’t know if there’s enough evidence to make an arrest, but I believe you.”

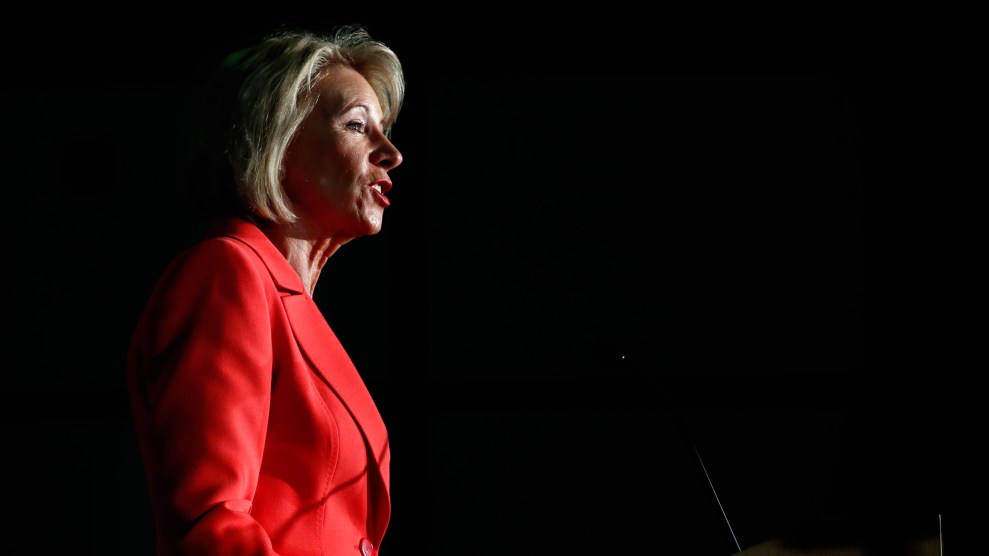

RELATED: Betsy DeVos Is Being Sued for Rolling Back Campus Protections for Sexual Assault Victims

Abbie’s speech opened a two-day training in the Hudson River Valley for officials who investigate sexual assault on college campuses. It was put on by a local rape crisis center and the Campus Sexual Assault Victims Unit, which is trying to fix the way cops handle sexual violence among college students, starting with how they talk with—and listen to—survivors. The unit, the first of its kind, was created by a 2015 law that required all universities and colleges in the state to adopt “yes means yes” affirmative consent policies and guarantee the rights of sexual assault survivors. It launched in March 2016 with a dual mission: reduce sexual violence on campuses and get more victims to file police reports.

Efforts to address sexual assault at colleges have usually focused on improving schools’ internal investigations, which often go easy on perpetrators while causing survivors to drop out. Now, a year after Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rolled back federal guidelines that made it easier for schools to discipline perpetrators, the victims unit wants survivors to reconsider an option many see as an uncomfortable last resort: contacting law enforcement.

It’s a daunting goal. There are more than 1.2 million college students in New York, and studies suggest that 20 percent of undergraduate women and about 6 percent of undergrad men experience sexual assault. Yet fewer than a quarter of sexual assaults on female college students are reported to police, according to the Justice Department. That’s in part because many survivors believe the cops can’t or won’t do anything to help them. According to one study, as little as 10 percent of all sexual assault reports result in felony charges.

“We need to do a better job holding perpetrators accountable,” says Technical Lieutenant Gary Kelly, the unit’s leader. “Until we do that, we’re not going to get those numbers up.” An energetic 55-year-old fond of puns, Kelly has spent the bulk of his three-decade career immersed in rape, abuse, and murder cases. The 12 senior investigators who make up his team collect reports of sexual violence across most of the state. They visit campuses ranging from business institutes to beauty schools, encouraging victim advocates, nurses, and administrators to contact them whenever a survivor wants to file a police report. They also coach cops and other investigators on how to field these reports without victim blaming. Niagara County District Attorney Caroline Wojtaszek approached the unit for assistance in 2017 after she watched body camera footage of a local officer who came across a woman who had just been raped. The suspect was still on the scene, yet the officer let him go and scolded the woman for being out late and away from her children. (The attacker later committed another sexual assault.) After viewing the recording, Wojtaszek says, she asked the investigator for the regional campus victims unit to train her county’s 358 sworn officers.

RELATED: This Serial Campus Rape Case Is a Textbook Example of the Struggle Accusers Face in Court

Some unit members told me they see their mission as cultural change. “We live in a society where we condone the objectification of women,” Kelly says. “And the people who have their opinions formed as a result of that are on the juries.” His approach is shaped by lessons of the child abuse panic of the ’80s, when social workers and detectives subjected kids to repeated interrogations using leading questions, resulting in a rash of false testimony and wrongful convictions. That crisis led to reforms in how child abuse is investigated, and Kelly believes similar fixes are overdue to investigations of sexual violence against adults. “We’re coming to the realization that things need to change,” he says.

Many police officers have learned to doubt victims’ credibility “from their senior men—and they learn it from their senior men,” unit member Judith Trimboli explains. “What’s taught ends up being 60 years old.” A senior investigator with a high tolerance for caffeine and a penchant for sarcasm, Trimboli has been a cop since 1984, when case data was stored on punch cards and “women weren’t wanted in law enforcement.” Now she’s one of the most experienced investigators on the campus victims unit. The victims unit emphasizes the importance of basic police work that may be neglected by officers who assume they’re handling a “he said, she said” case. It also pushes investigators to recognize their own biases. At the upstate training, unit members urge attendees to be honest with themselves about whether they believe some victims are “asking for it” or that many people lie about being assaulted. An agent from the Transportation Department inspector general’s office is skeptical when Kelly explains that only 2 to 8 percent of sexual assault reports are false. “I thought it was higher,” the agent says afterward. “Fifty percent.”

Trimboli frequently advises cops who want to do the right thing but don’t know where to begin. She recalls a recent incident when a female trooper called her for help with a possible domestic violence case. A young woman sitting in the trooper’s interview room was struggling to coherently describe some sort of frightening relationship, but the frustrated trooper couldn’t understand what had happened. A few days later, Trimboli interviewed the young woman using a recently developed technique known as the Forensic Experiential Trauma Interview. FETI, as it’s called, relies on open-ended, empathetic questioning. Instead of prodding a victim, “Why did you wait until today to report?” an officer may say, “Help me understand what brought you here today.” If a victim responds with an inconsistent, imprecise, or fragmented story, as many do, interviewers are trained to see it as a consequence of the brain’s defensive reaction to trauma, rather than a signal that she’s lying.

The technique not only increases the likelihood that a survivor will cooperate, but also uncovers more leads for investigators to follow, according to the victims unit. Trimboli’s FETI interview produced a clearer picture of what had happened. Trimboli says the young woman shared that their conversation helped her sleep through the night. And the trooper later told her, “If I knew how to do what you just did, I wouldn’t have had to go home and drink a whole bottle of wine.”

RELATED: How Baltimore Police “Seriously and Systemically” Failed Sexual-Assault Survivors

But in terms of hard numbers, the victims unit still has a ways to go. The number of survivors who make police reports remains small, says Michelle Carroll, who heads the campus branch of the New York State Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Prosecutors filed charges in 22 percent of the nearly 190 sexual assault, stalking, and domestic violence cases the unit handled during its first two years. (National statistics are spotty, but charges are filed in anywhere from 7 to 27 percent of forcible rape cases in the United States.) The unit will not pursue a criminal investigation against a victim’s wishes unless someone could be in danger. And while the unit is bringing the full force of its expertise to cases that might have been quietly closed a few years ago, getting convictions is another matter. Kelly still seethes about an old case in which a 20-year-old reported to police that she had been raped after passing out at a party. A cop lined up a confession, a written apology from the perpetrator, and a prosecutor willing to try the case, only for the jury to let the guy walk. “That’s what we’re up against,” Kelly says.

The unit’s success may be best measured not by how many predators it puts in prison, but by how it helps survivors heal. Abbie admitted that even with the support of her unit investigator, she still regretted putting herself through the stress of pressing charges. (Her attacker was convicted and sentenced to probation.) It’s common for survivors to find that the criminal justice system cannot bring them closure, Trimboli says. She’s heard victims say things like, “If we get that conviction, I’m going to feel whole again.” But after a perpetrator pleads guilty or a jury convicts, it can seem like a “hollow victory,” she says. “It’s how you treated them that’s going to have the most impact.”

This story was supported by DisHonorRoll, which is made possible through a grant from the Media Consortium.