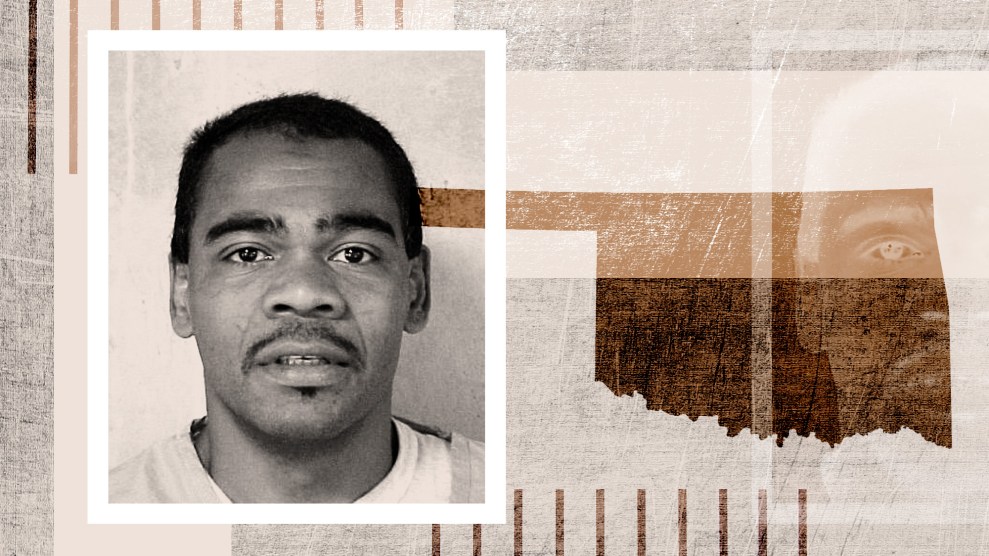

Mother Jones illustration; Oklahoma Department of Corrections/AP

Patrick Murphy didn’t say he was innocent. In the summer of 1999, when Murphy, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of eastern Oklahoma, killed his girlfriend’s ex-lover, also a Creek member, slashing his throat and cutting off his genitals before leaving him to die and then attempting to kill the man’s son, he soon confessed the crime to his girlfriend and cousin. And after he was brought to court, Murphy, then 30, was sentenced to death in 2000.

But since his sentencing, Murphy, six feet tall with a salt-and-pepper mustache, has put up a fight that has spanned nearly two decades and both state and federal court. So far, it has kept him alive. And Murphy’s case, which was heard by the US Supreme Court late last month, has also burst open questions about land and tribal sovereignty in Oklahoma. It could, depending on how the court rules, affect hundreds or even thousands of Native Americans already convicted in the state.

At the heart of Murphy’s case is land, and whom it belongs to. By the time Oklahoma became a state in 1907, white settlers had taken over large swaths of Creek land, leaving the natives with little sovereignty over the areas they’d once inhabited as a community. Though the majority of Creeks still live in the same area they did at the turn of the 20th century, there is no reservation. That’s why Murphy was brought to justice by a state court: Felony crimes committed on tribal land are considered to be under federal jurisdiction. But Murphy’s lawyers have pointed out what they say is a big hole in the state’s case: The 1866 treaty establishing the boundaries for the Creek Nation was never officially disbanded by Congress. An appeals court agreed—the Creek reservation was never formally disestablished, Murphy’s crime took place on tribal land, and thus, Murphy should be retried. Crucially, federal law prohibits the death penalty in crimes committed on tribal land, unless the tribe makes the rare move of supporting the sentence—meaning Murphy could have another shot at life if his efforts are successful.

The Creek tribe has taken on Murphy’s cause, filing an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief in support of its member. If the court sides with Murphy, the Creeks will, going forward, be ruled by their own government and courts, affecting everything from local taxes to civil law. And the responsibility of adjudicating crime on Creek land will fall instead to the federal government and, in minor crimes, the tribe—not Oklahoma.

This last point is perhaps what worries the state the most. If the court rules in favor of Murphy, the state says, it logically follows that any other tribal member (or non-member whose victim was Native) who was tried on a serious charge, usually a felony, by state prosecutors after committing a crime within Creek borders would be able to appeal their conviction and have their case retried in federal court. And according to the state, this new line of argument is already cropping up: Defendants have invoked the appeals court’s decision in at least 46 cases between August 2017, when the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, and February 2018. Oklahoma lawyers cautioned that a ruling in favor of Murphy would force the feds to potentially reopen more than a thousand cases committed on Creek land each year. In court filings, the state also expressed concern about the non-Native Americans currently living on tribal land, arguing that because non-Natives cannot hold positions in tribal governments, they will be unfairly impacted by tribal regulations and laws.

What’s more, the state says an affirmative ruling could leave the door wide open for the four other tribes in Oklahoma—Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole—whose reservations were abolished by statehood to challenge their status and push for sovereignty.

Chrissi Nimmo, deputy attorney general for the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, which submitted a friend-of-the-court brief in support of Murphy, says the state’s concerns are overblown and that a decision in favor of Murphy won’t automatically apply to the four other Oklahoma tribes. Although the act that established Oklahoma’s statehood applied to all tribes equally, each tribe’s treaty with the state differs, meaning each tribe would likely have to pursue a case separately. And, says Nimmo, a win for Murphy does not necessarily mean other convicted tribal members will have the same luck. Still, if Murphy wins, Oklahoma courts can expect to see a lot of appeals.

“We think about this [decision] more as a shield than a sword,” says Nimmo. “What you’re not going to see is tribes attempting to enforce their laws, regulations, whatever, on non-Indians. What you very well may see is a tribe saying to a state, ‘Your law and regulations don’t apply to us on our land.'”

That sentiment could apply to more than just criminal law. At lesser issue in Murphy are the rights of the oil and natural gas companies who work on Creek land. The Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, which represents more than 2,200 oil and natural gas operators in the state, filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the state, saying that a decision in favor of the tribe will disrupt their business by imposing “confusing and overlapping tax regimes, a patchwork of varied environmental regulations, and new and possibly inconsistent licensing and zoning regimes.” Oklahoma, the brief notes, is the third-highest producer of natural gas in the country and the fifth-highest producer of crude oil. And they may have a new ally on the court. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, as my colleague Rebecca Leber has written, has often turned a skeptical eye to environmental regulation, meaning he may be more inclined to side with business interests, i.e., the oil and gas magnates who want the 10th Circuit ruling overturned.

It’s unclear whether the court will be sympathetic to the Creeks. Justice Neil Gorsuch, the only justice with a solid background in tribal law and who tends to side with tribal interests, recused himself because he served on the 10th Circuit court while it was hearing the case. Last month’s arguments suggest the decision will likely fall along party lines: Conservative justices Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito appeared to lean toward supporting the state and overturning the appellate court’s decision, while more liberal members Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor took the opposite view. It’s unclear where Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and John Roberts stand. If the court splits 4-4, the lower court’s decision, which ruled in Murphy’s favor last summer, will automatically be affirmed.

The state is well aware of the gravity of the case. “If not corrected, the [10th Circuit’s] decision,” the state wrote in a passionate plea to the Supreme Court, “could result in the largest abrogation of state sovereignty by a federal court in American history.”