The Saturday after George Floyd was killed, Abu Bakr Bryant, a 29-year-old from Minneapolis, found himself walking dazedly among the charred remains of Chicago Avenue, the street where Floyd took his last breaths. Shops and restaurants smoldered. Windows had been boarded up. A melted stoplight hung midair like a piece of abstract art. He had on his person the entirety of his worldly possessions: a change of clothes, his cellphone, and his wallet. Bryant had been living out of his car until the previous evening, when he went to protest. The protests turned into firestorms, and when he got back to his car, he found that it was on fire, too.

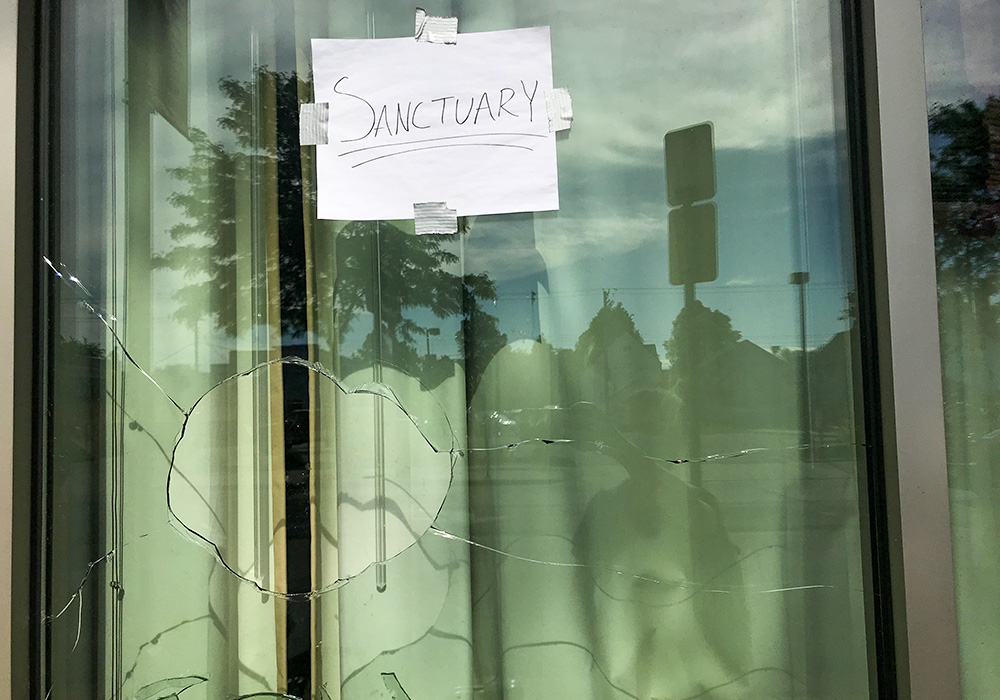

Nine blocks north of the intersection that had turned into a memorial to Floyd, Bryant passed by a former Sheraton hotel with handwritten signs saying “sanctuary” taped on the windows. With the exception of a couple holes from rocks thrown at the double-paned windows, the building was miraculously unscathed. He walked in and asked to use the bathroom. The people inside offered him food and a hotel room—for free. “I thought it was a joke,” he told me.

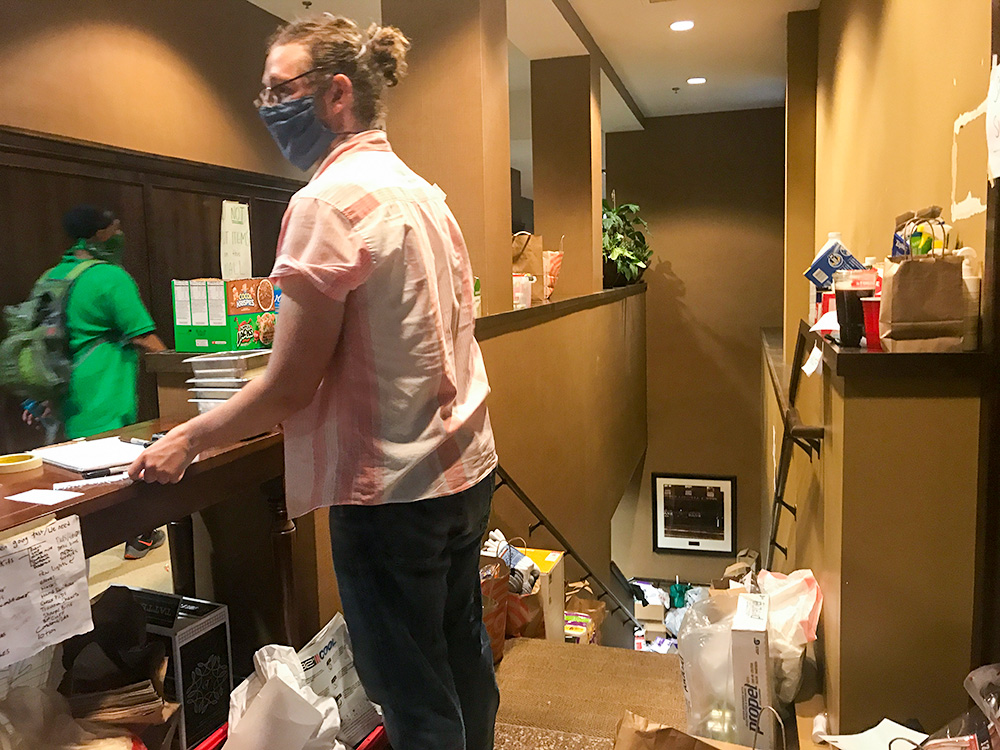

The 136-room hotel had been transformed into a pop-up homeless shelter of sorts, with no staff and virtually no rules. The hotel’s typical guests had been ordered to evacuate when the protests in Minneapolis heated up. In their place now were between 200 and 300 previously unhoused people—no one knew exactly how many—with more arriving each day to be put on a waitlist. When I visited for the first time, in early June, residents napped on leather sofas in the lobby using hotel sheets and pillows. Behind the bar, volunteers handed out chicken fajitas. Food donations filled the kitchen and the walk-in fridge.

The hotel teemed with volunteers, part of an ever-shifting collection of 120 servers, artists, medics, librarians, social workers, and others. From the start, the operation was democratic and decentralized—there was no hierarchy, no fund for donations, no spokesperson, not even a name (one suggestion was the “Share-a-Ton”). Many were wary, one volunteer said, of “nonprofitizing.” A variety of people-centered belief systems informed the volunteers’ work. Some were Democratic Socialists. Some were students of the radical Catholic Worker Movement. Many of the volunteers were veterans of the protests at Standing Rock; the leather chairs and wall-to-wall carpet evoked the Prairie Knights Casino, where organizers charged phones and washed up.

The whole thing had a dreamlike quality, and indeed, the details of the operation are still hazy. The owner of the Sheraton, a hotelier named Jay Patel, was a mystery. When I first visited, I saw him chatting with a volunteer, but he declined to comment, as he would continue to do in the days to come. There seemed to be as many interpretations of what was happening at the hotel as there were people in it. “This is not an occupation,” one volunteer told me. A few days later, another described it as “somewhat of a commandeering of a hotel.” At a press conference, yet another said: “This is a means of land repatriation. This is a means of addressing historic deep disparities.”

While no one seemed to be in charge, somehow, overnight, the operation provided not just the services of a hotel—complete with volunteers pushing carts of linens down the halls for housekeeping—but a health clinic and a donation drop-off site. What had been a conference room now bore hand-drawn signs saying “HARM REDUCTION,” with condoms for the taking and Narcan at the ready. Residents were encouraged to participate in tasks and decision making, and, together with the volunteers, they had nightly meetings to discuss things like the name and security of the sanctuary.

“It’s okay that you and I don’t understand it, because that’s what’s happening here,” said Alondra Cano, the council member overseeing the neighborhood, when I asked her about the hotel ownership and funding structures. “Systems are bending and adjusting to the new reality and a moment of crisis and that’s good. That’s the kind of radical mutual aid example that is being given birth to in this moment of crisis.”

She’s right: In communities across the country, there’s an air of wanting to scrap the system and start over, of the impossible suddenly becoming possible, of a door opening—as the writer Rebecca Solnit wrote in a 2009 book about altruism in the wake of disaster—“back into paradise, the paradise at least in which we are who we hope to be, do the work we desire, and are each our sister’s and brother’s keeper.” In Seattle, protesters claimed a handful of blocks near a recently vacated police precinct, naming the area the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. In the Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis, named for the abolitionist Wendell Phillips, people began building a different sort of civic infrastructure on the ashes of an old one that had failed so much of the population—pop-up food pantries replaced grocery stores that had been boarded up and torched; neighborhood security teams stood guard against the reported white supremacists and arsonists in their midst; and of course there was the Share-a-Ton, providing respite to whoever wandered in. It was a city within a city, provisional and fragile but constructed in what Zach Johnson, one of the key organizers of the Sheraton operation, calls a “radical moment of possibility.”

“We are the petri dish,” a shelter volunteer, whom we’ll call Angela to protect her privacy, said soon after the hotel’s transformation into a sanctuary. “We’re the experiment.”

Some of these early rebuilding efforts have flourished. Some have found themselves menaced by the same forces that made the old order unlivable: cops, racists, decades of structural inequity, even their own internal havoc. The stakes feel higher than ever: “The city stands in a place to set a precedent that could ripple out,” said organizer Thorne LaPointe at a recent community meeting, just before Minneapolis City Council members vowed to defund the Minneapolis Police Department. “This city has the world’s attention.”

When I asked Bryant what he made of the effort, he told me, “I never met Mr. Floyd, but from what I’m learning from his story and everything that led up to that event of him dying is that people prejudged not only his situation, but prejudged him, and prejudged what was going on.” We were sitting on a bench just outside the hotel. To our right, on the hotel facade, hung a banner reading “Keys not cuffs.” To our left, plywood signs spray-painted with Black Power fists greeted visitors at the hotel entrance. Floyd’s presence permeated the hotel: Several of the residents personally knew him; he’d been a security guard at the city’s largest homeless shelter. Brookie Flying Hawk Muñez, a hotel resident who uses a wheelchair, told me that Floyd always advocated for her because of her lack of mobility. “They’d say, ‘Well we don’t have a bed open for her,’” she remembered. “George Floyd would say, ‘Nope, we’re gonna make room for Flying Hawk.’”

Outside the hotel, Bryant continued: “Everybody here has a story on how they ended up in whatever predicament. Maybe this is a way for people to start opening up and giving each other a chance, you know?” This was Tuesday, June 2, just a few days after that chance seemed to materialize out of thin air. A week later, it was in the process of vanishing.

Julia Lurie

The origin story of the repurposed hotel goes like this: In the days following George Floyd’s death, the Phillips neighborhood, home to one of the city’s largest homeless encampments, turned violent. Those without housing were already vulnerable to the coronavirus, and now they were caught between the pandemic, the fires, the protests, and the National Guard. Zach Johnson, a housing activist who leads a nonprofit aligned with the Catholic Worker Movement, and Rosemary Fister, an organizer and nurse practitioner, personally knew a couple who were staying in a tent in the neighborhood. They bought the couple a room at the hotel on the evening of Friday, May 29, the day after the Minneapolis Police Department’s Third Precinct burned to the ground. It was a solution they’d been pushing citywide as part of their work with the newly formed Can’t Stay Home Without Housing initiative. For weeks, the group had been urging the city officials to place more individuals without housing into hotels sitting empty around the Twin Cities, as other cities have done.

When Johnson and Fister visited the hotel on Saturday afternoon to deliver a care package, they learned that hotel management planned to evacuate the hotel in two hours in response to the protests. In the elevator, as Johnson recalled, “we looked at each other and said, ‘Well, here’s the window.’” If they were going to try to house people in an empty hotel, now was their moment.

The need throughout the city was acute even before the arrival of the coronavirus, and it was distributed unevenly along racial lines. Homelessness across the state increased by 10 percent between 2015 and 2018, according to the Wilder Foundation’s Minnesota Homeless Study. In Hennepin County, which includes Minneapolis and its western suburbs, Black people make up 14 percent of the population but half of its homeless population. Native Americans, just 1 percent of the population, make up 15 percent of its homeless. “Simply put,” the study concludes, “many people are staying outside of the formal shelter system because there is nowhere else to go; shelters are at capacity and there is no available affordable housing.”

In 2018, an encampment of some 200 unhoused people, predominantly Native American, sprouted up on Hiawatha Avenue in the Phillips neighborhood, just a mile from the Sheraton. City officials moved the individuals living there to a navigation center, which in turn shut down last year, spilling people back into the streets. When another big encampment popped up on Hiawatha earlier this year, dubbed Camp Quarantine, alarmed city officials put a fence around it to keep it from growing, citing health and safety precautions. On May 28, officials cleared the camp as fires smoldered nearby. The couple for whom Johnson and Fister bought a hotel room on the following day had come from that encampment.

Over the ensuing hours on that Saturday, May 30, Johnson and another organizer friend sat in the hotel lobby at the Sheraton and negotiated with hotel owner Jay Patel to let homeless people stay there. As the city’s newly imposed curfew drew closer, other organizers gathered at the Sheraton too. They made calls to local politicians and progressive donors, who in turn hopped on the phone to figure out “what it is we can do in the very moment to ensure safety,” said a person who was on the call. “We had a complete and total breakdown of government, and there was no confidence that the government was going to help us out here.” Ultimately, the organizers raised money to rent a block of 20 rooms that night. They offered to protect the hotel and ensure that in the ensuing nights of chaos, the hotel wouldn’t burn down.

According to Johnson and others involved in the negotiations, Patel was wary; taking on the liability of a homeless shelter could spell financial ruin. At the same time, he refused the money that was offered him, according to those closely involved with the negotiations. Over the next 24 hours, as fires broke out, 150 homeless people streamed in. Patel didn’t turn them around.

By Sunday, the day after the negotiations with Patel, “it was very difficult to quantify how many people were there because it wasn’t like a straightforward hotel situation,” said Sheila Delaney, a housing activist and volunteer at the hotel. “It was also being used as a sanctuary, where anyone who needed to get shelter literally from the storm that was going outside could come in.” By Monday, there were 300 residents, 400 more on a waitlist, and a “ragtag group of volunteers,” said Johnson. It was, by his estimation, the “most radical harm reduction shelter I would guess anybody’s ever seen.”

Patel, who owns hotels in Minnesota and South Dakota, and who had the inopportune timing of buying the Sheraton just before the coronavirus outbreak, reportedly told volunteers that he let homeless people stay at the hotel because he wanted to help the community. In the days to follow, he was less and less a visible presence at the hotel. Stories began to spread among volunteers about his personal history, financial status, and motivations. He was said to have soured on the shelter initiative, perhaps not appreciating that those who had come for the night had intended to stay.

Volunteers and residents alike knew how this looked to outsiders. “I have heard some comments to the effect of, ‘They need to follow a process. Why don’t they just work through the regular formalized institutional processes?’” said Delaney. “What I want people to know is that people have been trying for years and years and years, and we just simply don’t have enough beds. Period.”

The second evening that the hotel was filled with formerly unhoused residents, a team of cops showed up at the old Sheraton in riot gear. In a video the volunteers shared with me, cops can be seen bending down next to the tires of a truck in the hotel parking lot that volunteers had used to block the entrance. The volunteers later found the tires slashed. The Minnesota Department of Public Safety’s Lt. Gordon Shank told me, “We don’t believe troopers deflated any tires at that location,” but the department has confirmed that cops strategically slashed tires near protest hot spots that same weekend.

Cops came again in the wee hours the next day, a few minutes before curfew lifted, and found a hotel resident in a car in the hotel parking lot. Videos show the cops wandering the parking lot outside, shining strobe lights into the floor-to-ceiling windows of the lobby, behind which residents had gathered just feet away. Cops pull the resident out of the car and put him in zip-tie handcuffs. “That was terrifying, because we’re trying to keep people safe,” said Angela. “All over the building we have signs that say ‘sanctuary,’ ‘safe space.’ I don’t understand how someone can lack empathy so deeply to believe that they can do that to a sanctuary.’” Ultimately, Angela said, the cops left without charging the man with anything.

There was also the evening when, well past curfew, a pickup truck and an SUV crept past the Sheraton. Inside were white men in black masks with guns. Some of them leaned out the window as the cars slunk by. Angela assumed the men were white supremacists, but they, too, could have been cops: Unicorn Riot reported that during the first days of unrest, some officers had taken to driving around in unmarked dark cars, wearing dark clothes.

The intimidation wasn’t limited to the hotel, of course. In the early days of the Minneapolis uprising, said Delaney, the shelter volunteer, “We were all being intimidated by the cops—even those of us who were just sitting on our steps.”

During the day, Angela is an archivist at a University of Minnesota library housing the Black history archives, where she catalogs things like archival receipts for slaves from large plantations and Black Panthers ephemera. All that history crashed up against the present for her when the cops in Minneapolis came to the hotel and when, in the days after Floyd’s death, Angela stood on the front lines of protests as cops shot rubber bullets and tear gas. “You relive every trauma you’ve ever had and ever heard about,” said Angela, who is Black. She thinks a lot about the uprisings—the slave rebellions, the civil rights movement. “It’s a weirdly spiritual moment—I don’t know if that’s the right way to put it—but I can feel my ancestors,” she said. “My ancestors are just like, ‘Be careful.’”

On a recent afternoon, I stumbled upon four massive grocery distribution efforts in the space of a few blocks of the repurposed Sheraton. At a high school, organizers had turned a classroom into a food distribution command center. On the sidewalk, the local Islamic center had set up tables of snacks and drinks. Bags filled the parking lot of Mercado Central, a Latinx marketplace that had been looted and nearly blown up during the protests when someone turned on all the gas. At the Center of Discipline, a nonprofit boxing gym for at-risk youth, dozens of volunteers packed bags of groceries, which filled the boxing rings and scrunched between the elliptical trainers.

“Most of these people that are in here doing volunteer work—we don’t know them,” said Jeanne Montrese, vice president of the Center of Discipline board. “They don’t come to the gym normally—they’re just from the community and just decided to help.”

Julia Lurie

In the wake of Floyd’s death, in the subsequent days of fires and flash bombs in her neighborhood, gym regular Sierra Leone Samuels was, as she put it, “pretty messed up.” The only thing that helped was going outside and walking the streets during the day with her son. “The first thing I noticed was the amount of people that were getting up and coming out with brooms and dustpans and just starting to clean,” she said. “No one asked anybody to do anything.”

Phillips is one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. More than a third of its residents live below the poverty line. It’s also among its most diverse—a hub for Minneapolis’ Latinx, Native, and Black businesses and organizers. Somali restaurants abut Mexican grocery stores. The neighborhood was the birthplace of the American Indian Movement, back in the ’60s, and the home today of Little Earth, the nation’s first urban housing complex for Native Americans. The big event of the year is the May Day Parade, when 50,000 people fill the streets.

There is undeniable beauty to the way that these altruistic outlets rose up in Phillips, literally out of the ashes, in an area characterized by disinvestment. But the privation here has outstripped the capacities of the mutual aid efforts. The reason I’d noticed distribution centers was because of the lines down the sidewalk of people who needed food for compounding reasons: They lived in neighborhoods where stores were shuttered or burned down during the protests. And then the city shut down all public transportation for several days due to the protests, virtually stranding those without cars, many of whom were already suffering from the financial stress brought on by COVID-19.

“There’s absolutely nothing open for anybody to get anything,” said Samuels. “There’s no grocery stores. There’s no gas stations. There’s no pharmacies. The post office burned….It’s been really hard on the community.”

A week after Floyd’s death, as she oversaw volunteers packing grocery bags in a neighborhood still smoldering from the fires, Montrese herself seemed unfazed. “I mean, we do this all the time,” she said. “Most of the people who come here are minorities: Hispanic, Native American and African American, Asian. So they already have problems and disparities. It’s always a crisis of something. It’s just been exacerbated by these situations.”

Pimento Jamaican Kitchen, a rum bar and a venue for everything from reggae lessons and dance parties to radical healing circles, has also transformed into a relief center, with an ant colony of volunteers packing bags of food groceries and protest supplies. Canned goods, toothpaste, lightbulbs, baby clothes, and other basics filled the floors and the bar. In the fridge where the rum punch could usually be found was insulin; in the lounge were eyewash and suture kits for protesters. The back patio was piled high with diapers and toilet paper. “We’re like a Walmart almost,” said Scott McDonald, the Pimento booking manager who coordinated the effort.

Pimento has had its scares, too—in the first days of curfew, a volunteer security team of 60 people took shifts guarding the restaurant. The same evening that homeless people were filing into the Sheraton, Pimento’s security team had to evacuate after shots were fired in the street, allegedly by a white man in a sedan. “There are videos of me, with white supremacists talking about trying to find me,” said McDonald. He wasn’t at all surprised by the threats. “Any time people of color decide that they want to take care of themselves and try to heal themselves, there’s always going to be threats. There’s always going to be threats when white fragility is threatened.”

Julia Lurie

So it went in the improvised world created in the early days of Minneapolis’ uprising. Hotels became de facto affordable housing, and boxing rings and restaurants became de facto grocery stores, and normal people turned into first responders and security guards.

Residential neighborhoods formed teams equipped with block leaders, text groups, and schedules for sitting out on stoops with fire extinguishers. I ran into these community security guards repeatedly as I walked home around midnight after reporting on a protest. From their stoops, they asked me who I was, and then if I needed help. One man said he would walkie-talkie his neighbors down the street so they would know to expect me. (To state the obvious, my being a white woman undoubtedly helped smooth my passage. The hypervigilance has led to some to be overzealous with their vigilantism, vandalizing cars they don’t recognize or posting online about threatening people walking down the streets who are, in fact, their neighbors.)

Among the security teams was a group that has been dubbed the “fly team,” comprising mostly twenty- and thirtysomethings who volunteered to break curfew so they could provide emergency services to people in need during the worst of the violence. If they got word that something was on fire or if someone was unsafe, a dispatcher blasted the group’s Signal thread. When shots were fired near Pimento, a dispatcher from the fly team sent out volunteers. When a young Black man found himself stranded in a heavily militarized area—his car tires slashed in a Kmart parking lot full of cars with flat tires—he called the dispatch team. In the week after the protests, the fly team members I spoke to said they had barely slept. “Once it starts getting dark, any moment you’re not looking at the dispatch, I just feel really guilty,” said Wahida, a server at a restaurant and a fly team member. “I said to my partner last night, what if we just watched a TV show? Can you imagine? That would feel insane.”

It was Wahida and her friend, Grant, who rushed to pick up the stranded man in the Kmart parking lot in the early hours of May 31. On their way, they turned a corner onto a street that had become a police staging area and were met with rubber bullets. “The force shook my entire car and shattered my windshield,” Grant recalled. A picture he shared shows shattered glass in a bullseye just behind the steering wheel.

It’s easy to be cynical about the team: Wahida and Grant, like many of its members, have no experience with first response. They had some gear that they’d read was useful for fighting fires—extinguishers, hoses, and buckets, plus an ax and a sledgehammer for breaking down doors—but they weren’t sure what exactly to do with them. Grant carried a 9-inch knife for self-defense. (“We don’t have guns because we’re liberals,” he explained.) Asked why she felt compelled to violate curfew and put herself in harm’s way, Wahida replied, “The answer is, we don’t have any other options, because there’s not anyone out there trying to protect the communities that we live in.”

Wahida and Grant’s efforts echo those of the Native, Black, and Latinx communities, which mobilized armed security forces in an attempt to protect property and people during the protests. A team of 150 volunteers patrolled homes and businesses in the Franklin corridor, a section of the Phillips neighborhood that’s home to many Native-owned homes and businesses. They rolled through the streets armed with guns and baseball bats. In a Facebook post congratulating the community for their work, Michael Goze, head of the American Indian Community Development Corporation, wrote, “Many were at Standing Rock and had seen the National Guard before and were not willing to let them Protect US!” Minneapolis NAACP recruited roughly 50 volunteers, some toting assault rifles, to stand guard outside Black-owned businesses in North Minneapolis. They called themselves the Minnesota Freedom Riders, after the civil rights activists who rode buses into the segregated South.

Katherine Vasquez, an 18-year-old whose parents own a stall at the vandalized Mercado Central, was among a security team that local businesses put together during the protests. With her mother, she chased away several prospective looters. She tried to call the cops during one particularly incendiary evening, but they didn’t come. “It’s honestly very tough because at night we have to stay up to protect what’s ours, we go home, we sleep for like two hours, we come back to help protect and give out to the community,” she said, when we spoke outside Mercado’s pop-up food relief station. The day before, she had attended her virtual high school graduation.

Even councilmember Jeremiah Ellison, son of state Attorney General Keith Ellison, patrolled the streets with a pistol and a fire extinguisher. “I was excited to fight over the budget,” Ellison told the Washington Post. “I don’t think anybody could have pictured this.”

The local organizing didn’t come out of nowhere: When Goze wanted help securing the streets, he worked with American Indian Movement Patrol (AIM Patrol), which got its start in the 1960s as a citizen patrol group aimed at documenting and deescalating police violence against Native Americans. Advocacy groups Reclaim the Block, Black Visions Collective, and MPD150 have garnered national attention over the past few weeks, but they have been around for years, calling to defund the police. MPD150 emerged in 2017, when it released a report reviewing the city police department’s 150-year history. “We thought it’d be a good time for a performance review,” said Ricardo Levins Morales, who helped start the group. The report concluded that police “cannot be reformed away from their core function” and pushed for city officials to move money from the cops to other community-led safety initiatives. “We nodded our heads and said, ‘Good stuff, kind of utopian,’” said Peter Rachleff, a retired professor at Macalester College and founder of the East Side Freedom Library. “And then all of a sudden it becomes material—it becomes something to put on the table.”

“You plant the seeds, you work them into the soil, and eventually it’ll rain,” said Morales. “We had no idea we were going to get a monsoon this quickly.”

Listen to Julia Lurie report from Minneapolis on the Mother Jones Podcast.

But in this new world of underground first responders and radical possibility, many of the old rules still apply. When Wahida and Grant eventually arrived at the Kmart parking lot, the stranded man was handcuffed there for breaking curfew. Cops checked out Grant’s car, found the sledgehammer, the ax, and the knife, and figured they’d come upon a couple of violent rioters. “They find this very illegal 9-inch blade in our car, they freak out, pull out their guns, say we’re under arrest and all that,” Grant recalled. Of the three people breaking curfew, Grant was the only white person. He’s 6-foot-3, with blond hair and a thick Minnesotan accent. He deployed what he called his “good old police officer shtick.”

“I just pretended to be really ignorant—that I had no idea I was gonna get arrested, I was afraid for my life, I was afraid of the rioters,” he said. “I succumbed to whatever they wanted to hear to make them feel like they were doing something good.” The thing about white privilege with cops, he went on, “is you just have to pretend you’re on their team. There’s this weird code and it’s sick, but you can weaponize that to get out of these situations.”

Ultimately, the cops took the knife and let the three people keep the ax and sledgehammer and drive away in Grant’s shattered car.

Over the past week or so, as the protests have slowed in Minneapolis, the emergency dispatches over the fly team thread have come to a stop. The thread is still active, transformed into a community aid group of sorts, helping provide food and transportation to people in need. In the event of an emergency, the group is ready to mobilize, Grant said: “It’s kind of like if you build a police department and they all go out to fix a problem and they are all waiting for something to happen again.”

When I visited the old Sheraton again, a few days after homeless people had moved in, the utopian air of the project had been overwhelmed by need: The operation was still impressive, but it seemed now that there were too many residents with too many problems. People lined up for toiletries in the crowded lobby, blocking the elevators, which were themselves jam-packed. Few wore masks. There hadn’t been any more run-ins with the police, but the lack of structure internally that had seemed so admirable just a couple days before now seemed hazardous. One man walked around in a haze, seemingly unaware that his pants hung at his knees. Fights were reportedly breaking out as people became territorial about their space.

“We want everything to be communal because all the open spaces are communal and everyone is working together—but we still need and want to respect people’s property,” said Angela, the archivist. “So how do we do that and have a consistent message?”

“I went there to check it out for myself and I saw complete chaos,” said Goze, the head of the American Indian Community Development Corporation. “There was nobody in charge.” That is, of course, the whole point of a decentralized system. I had to remind myself that what struck my own eyes as chaotic was a sudden falling away of a status quo that wasn’t any better. Drug use was rampant, but it was safer for being done out in the open, and with others. My heart sank when I saw parents in the lobby with young kids, but a volunteer reminded me that if the family weren’t staying here, they’d be on the streets.

Without more resources, Johnson acknowledged, it seemed impossible to turn the short-term emergency refuge into a long-term shelter. “It became clear at least for me, this isn’t sustainable or healthy for anybody to try to superhuman-lift this thing off the ground,” he said. Organizers had been in touch with government officials, nonprofits, and philanthropists about who might take on the massive job of turning the shelter into a permanent fixture.

The volunteers were also increasingly skeptical of the racial dynamic of the hotel, which had begun to replicate the dynamic of other shelter systems: The volunteers were predominantly white; the residents were predominantly people of color. Fixing that—with empowered resident councils, culturally appropriate mentors, and partner organizations—required “time and intention,” said Johnson, “and we didn’t have either of those things without institutional support.”

On Monday, Patel reportedly called the Minneapolis Police Department to have the residents evicted. The cops didn’t come; evictions are temporarily forbidden under Minnesota’s emergency order. Early Tuesday morning, a fire alarm awoke the residents, spilling them into the parking lot. As they knocked on doors to evacuate residents, the volunteers found that one resident, staying in a room with his family, had overdosed. They administered Narcan and started CPR. Johnson encouraged the resident’s family to call 911, but they were nervous about doing so. “I did CPR twice in the past week there,” said Johnson. “And both times, it was the same thing: Residents were wary of calling 911.”

The volunteers had run into a harsh reality: The tempos of need and the tempos of provision were out of sync. The Share-a-Ton alone couldn’t fix the fact that the city had well accommodated itself to the suffering of certain people, that in fact so much of civic infrastructure had, for generations, failed those certain people. If you don’t call 911, whom do you call? It would take more than a team of committed volunteers and residents to create an answer.

Patel again ordered the residents evicted on Tuesday. This time, he wiped the key card software from the hotel computers, temporarily locking some out of their rooms. He had reportedly received notice of lease violations—drug use, accumulating garbage—in a letter from the property management company.

Volunteers told residents the news. “I told them that there was a calm, peaceful window where people could leave on their own terms, and there was no guarantee how long that was going to last based on what we know and don’t know about the owner,” said Johnson. At an emotional, last-minute press conference in the parking lot, residents said they had nowhere to go. They streamed out of the hotel, carrying bags and pushing carts of possessions. Organizers put out a call out for tents and sleeping bags.

Johnson seemed exhausted. He had made the personal decision to direct his time toward helping with relief efforts at the park near the Sheraton, where volunteers provided food, tents, and hotel vouchers. He had no illusions about the hotel’s future: “Class interests will rally around the owner.”

On Wednesday, for the last time, volunteers encouraged the remaining residents to leave. They would not be returning that night. When I called Abu Bakr Bryant later on, he was once again walking around the burnt-out neighborhood, toting a backpack with books and clothes. He sounded disappointed but measured. “I’ve been through this before,” he said. “I’m not gonna overreact.” He didn’t know where he would spend the night.