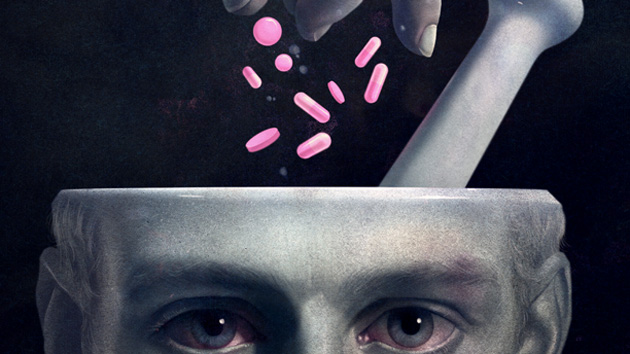

<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lexapro_pills.jpg">Tom Varco</a>/Wikimedia

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

This story first appeared on the ProPublica website.

The Ohio medical board concluded that pain physician William D. Leak had performed “unnecessary” nerve tests on 20 patients and subjected some to “an excessive number of invasive procedures,” including injections of agents that destroy nerve tissue.

Yet the finding, posted on the board’s public website, didn’t prevent Eli Lilly and Co. from using him as a promotional speaker and adviser. The company has paid him $85,450 since 2009.

In 2001, the US Food and Drug Administration ordered Pennsylvania doctor James I. McMillen to stop “false or misleading” promotions of the painkiller Celebrex, saying he minimized risks and touted it for unapproved uses.

Still, three other leading drug makers paid the rheumatologist $224,163 over 18 months to deliver talks to other physicians about their drugs.

And in Georgia, a state appeals court in 2004 upheld a hospital’s decision to kick Dr. Donald Ray Taylor off its staff. The anesthesiologist had admitted giving young female patients rectal and vaginal exams without documenting why. He’d also been accused of exposing women’s breasts during medical procedures. When confronted by a hospital official, Taylor said, “Maybe I am a pervert, I honestly don’t know,” according to the appellate court ruling.

Last year, Taylor was Cephalon’s third-highest-paid speaker out of more than 900. He received $142,050 in 2009 and another $52,400 through June.

Leak, McMillen and Taylor are part of the pharmaceutical industry’s white-coat sales force, doctors paid to promote brand-name drugs to their peers—and if they’re convincing enough, get more physicians to prescribe them.

Drug companies say they hire the most-respected doctors in their fields for the critical task of teaching about the benefits and risks of their drugs.

But an investigation by ProPublica uncovered hundreds of doctors on company payrolls who had been accused of professional misconduct, were disciplined by state boards or lacked credentials as researchers or specialists.

This story is the first of several planned by ProPublica examining the high-stakes pursuit of the nation’s physicians and their prescription pads. The implications are great for patients, who in the past have been exposed to such heavily marketed drugs as the painkiller Bextra and the diabetes drug Avandia—billion-dollar blockbusters until dangerous side effects emerged.

“Without question the public should care,” said Dr. Joseph Ross, an assistant professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine who has written about the industry’s influence on physicians. “You would never want your kid learning from a bad teacher. Why would you want your doctor learning from a bad doctor, someone who hasn’t displayed good judgment in the past?”

To vet the industry’s handpicked speakers, ProPublica created a comprehensive database that represents the most accessible accounting yet of payments to doctors. Compiled from disclosures by seven companies, the database covers $257.8million in payouts since 2009 for speaking, consulting and other duties. In addition to Lilly and Cephalon, the companies include AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co. and Pfizer.

Although these companies have posted payments on their websites—some as a result of legal settlements—they make it difficult to spot trends or even learn who has earned the most. ProPublica combined the data and identified the highest-paid doctors, then checked their credentials and disciplinary records.

That is something not all companies do.

A review of physician licensing records in the 15 most-populous states and three others found sanctions against more than 250 speakers, including some of the highest paid. Their misconduct included inappropriately prescribing drugs, providing poor care or having sex with patients. Some of the doctors had even lost their licenses.

More than 40 have received FDA warnings for research misconduct, lost hospital privileges or been convicted of crimes. And at least 20 more have had two or more malpractice judgments or settlements. This accounting is by no means complete; many state regulators don’t post these actions on their web sites.

In interviews and written statements, five of the seven companies acknowledged that they don’t routinely check state board websites for discipline against doctors. Instead, they rely on self-reporting and checks of federal databases. Only Johnson & Johnson and Cephalon said they review the state sites.

ProPublica found 88 Lilly speakers who have been sanctioned and four more who had received FDA warnings. Reporters asked Lilly about several of those, including Leak and McMillen. A spokesman said the company was unaware of the cases and is now investigating them.

“They are representatives of the company,” said Dr. Jack Harris, vice president of Lilly’s US medical division. “It would be very concerning that one of our speakers was someone who had these other things going on.”

Leak, the pain doctor, and his attorney did not respond to multiple messages. The Ohio medical board voted to revoke Leak’s license in 2008. It remains active as he appeals in court, arguing that the evidence against him was old, the witnesses unreliable and the sentence too harsh.

In an interview, McMillen denied nearly all of the allegations in the FDA letter and blamed his troubles on a rival firm whose drug he had criticized in his presentations.

“I’m more cautious now than I ever was,” said McMillen, who said he also does research. “That’s why I think a lot of the companies use me. I’m not taking any risks.”

Taylor said that the allegations against him were “old news” from the 1990s and that regulators had not sanctioned him. “It had nothing to do with my skills as a physician,” said Taylor, noting that he speaks every other week around the country and sometimes abroad. “Even my biggest detractors in that situation lauded my skills as a physician. That’s what’s most important.”

Disclosures are just the start

Payments to doctors for promotional work are not illegal and can be beneficial. Strong relationships between pharmaceutical companies and physicians are critical to developing new and better treatments.

There is much debate, however, about whether paying doctors to market drugs can inappropriately influence what they prescribe. Studies have shown that even small gifts and payments affect physician attitudes. Such issues have become flashpoints in recent years both in courtrooms and in Congress.

All told, 384 of the approximately 17,700 individuals in ProPublica’s database earned more than $100,000 for their promotional and consulting work on behalf of one or more of the seven companies in 2009 and 2010. Nearly all were physicians, but a handful of pharmacists, nurse practitioners and dietitians also made the list. Forty-three physicians made more than $200,000—including two who topped $300,000.

Physicians also received money from some of the 70-plus drug companies that have not disclosed their payments. Some of those interviewed could not recall all the companies that paid them, and certainly not how much they made. By 2013, the health care reform law requires all drug companies to report this information to the federal government, which will post it on the Web.

The busiest—and best compensated—doctors gave dozens of speeches a year, according to the data and interviews. The work can mean a significant salary boost—enough for the kids’ college tuition, a nicer home, a better vacation.

Among the top-paid speakers, some had impressive resumes, clearly demonstrating their expertise as researchers or specialists. But others did not –contrary to the standards the companies say they follow.

Forty five who earned in excess of $100,000 did not have board certification in any specialty, suggesting they had not completed advanced training and passed a comprehensive exam. Some of those doctors and others also lacked published research, academic appointments or leadership roles in professional societies.

Experts say the fact that some companies are disclosing their payments is merely a start. The disclosures do not fully explain what the doctors do for the money—and what the companies get in return.

In a raft of federal whistleblower lawsuits, former employees and the government contend that the firms have used fees as rewards for high-prescribing physicians. The companies have each paid hundreds of millions or more to settle the suits.

The disclosures also leave unanswered what impact these payments have on patients or the health care system as a whole. Are dinner talks prompting doctors to prescribe risky drugs when there are safer alternatives? Or are effective generics overlooked in favor of pricey brand-name drugs?

“The pressure is enormous. The investment in these drugs is massive,” said Dr. David A. Kessler, who formerly served as both FDA commissioner and dean of the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine. “Are any of us surprised they’re trying to maximize their markets in almost any way they can?”

From drug reps to doc reps

For years, drug companies bombarded doctors with pens, rulers, sticky notes, even stuffed animals emblazoned with the names of the latest remedies for acid reflux, hypertension or erectile dysfunction. They wooed physicians with fancy dinners, resort vacations and personalized stethoscopes.

Concerns that this pharma-funded bounty amounted to bribery led the industry to ban most gifts voluntarily. Some hospitals and physicians also banned the gift-givers: the legions of drug sales reps who once freely roamed their halls.

So the industry has relied more heavily on the people trusted most by doctors—their peers. Today, tens of thousands of US physicians are paid to spread the word about pharma’s favored pills and to advise the companies about research and marketing.

Recruited and trained by the drug companies, the physicians—accompanied by drug reps—give talks to doctors over small dinners, lecture during hospital teaching sessions and chat over the Internet. They typically must adhere to company slides and talking points.

These presentations fill an educational gap, especially for geographically isolated primary care doctors charged with treating everything from lung conditions to migraines. For these doctors, poring over a stack of journal articles on the latest treatments may be unrealistic. A pharma-sponsored dinner may be their only exposure to new drugs that are safer and more effective.

Oklahoma pulmonologist James Seebass, for example, earned $218,800 from Glaxo in 2009 and 2010 for lecturing about respiratory diseases “in the boonies,” he said. On a recent trip, he said, he drove to “a little bar 40 miles from Odessa,” Texas, where physicians and nurse practitioners had come 50 to 60 miles to hear him.

Seebass, the former chair of internal medicine at Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, said such talks are “a calling,” and he is booking them for 2011.

The fees paid to speakers are fair compensation for their time away from their practices, and for travel and preparation as well as lecturing, the companies say.

Dr. Samuel Dagogo-Jack has a resume that would burnish any company’s sales force: He is chief of the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Dagogo-Jack conducts research funded by the National Institutes of Health, has edited medical journals and continues to see patients.

While most people are going home to dinner with their families, he said, he is leaving to hop on a plane to bring news of fresh diabetes treatments to non-specialist physicians “in the trenches” who see the vast majority of cases.

Since 2009, Dagogo-Jack has been paid at least $257,000 by Glaxo, Lilly and Merck.

“If you actually prorate that by the hours put in, it is barely more than minimum wage,” he said. (A person earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 would have to work 24 hours a day, seven days a week for more than four years to earn Dagogo-Jack’s fees.)

For the pharmaceutical companies, one effective speaker may not only teach dozens of physicians how to better recognize a condition, but sell them on a drug to treat it. The success of one drug can mean hundreds of millions in profits, or more. Last year, prescription drugs sales in the United States topped $300 billion, according to IMS Health, a healthcare information and consulting company.

Glaxo’s drug to treat enlarged prostates, Avodart—locked in a battle with a more popular competitor—is the topic of more lectures than any of the firm’s other drugs, a company spokeswoman said. Glaxo’s promotional push has helped quadruple Avodart’s revenue to $559 million in five years and double its market share, according to IMS.

Favored speakers like St. Louis pain doctor Anthony Guarino earn $1,500 to $2,000 for a local dinner talk to a group of physicians.

Guarino, who made $243,457 from Cephalon, Lilly and Johnson & Johnson since 2009, considers himself a valued communicator. A big part of his job, he said, is educating the generalists, family practitioners and internists about diseases like fibromyalgia, which causes chronic, widespread pain—and to let them know that Lilly has a drug to treat it.

“Somebody like myself may be able to give a better understanding of how to recognize it,” Guarino said. Then, he offers them a solution: “And by the way, there is a product that has an on-label indication for treating it.”

Guarino said he is worth the fees pharma pays him on top of his salary as director of a pain clinic affiliated with Washington University. Guarino likened his standing in the pharma industry to that of St. Louis Cardinals first baseman Albert Pujols, named baseball player of the decade last year by Sports Illustrated. Both earn what the market will bear, he said: “I know I get paid really well.”

Is anyone checking out there?

Simple searches of government websites turned up disciplinary actions against many pharma speakers in ProPublica’s database.

The Medical Board of California filed a public accusation against psychiatrist Karin Hastik in 2008 and placed her on five years’ probation in May for gross negligence in her care of a patient. A monitor must observe her practice.

Kentucky’s medical board placed Dr. Van Breeding on probation from 2005 to 2008. In a stipulation filed with the board, Breeding admits unethical and unprofessional conduct. Reviewing 23 patient records, a consultant found Breeding often that gave addictive pain killers without clear justification. He also voluntarily relinquished his Florida license.

New York’s medical board put Dr. Tulio Ortega on two years’ probation in 2008 after he pleaded no contest to falsifying records to show he had treated four patients when he had not. Louisiana’s medical board, acting on the New York discipline, also put him on probation this year.

Yet during 2009 and 2010, Hastik made $168,658 from Lilly, Glaxo and AstraZeneca. Ortega was paid $110,928 from Lilly and AstraZeneca. Breeding took in $37,497 from four of the firms. Hastik declined to comment, and Breeding and Ortega did not respond to messages.

Their disciplinary records raise questions about the companies’ vigilance.

“Did they not do background checks on these people? Why did they pick them?” said Lisa Bero, a pharmacy professor at University of California, San Francisco who has extensively studied conflicts of interest in medicine and research.

Disciplinary actions, Bero said, reflect on a physician’s credibility and willingness to cross ethical boundaries.

“If they did things in their background that are questionable, what about the information they’re giving me now?” she said.

ProPublica found sanctions ranging from relatively minor misdeeds such as failing to complete medical education courses to the negligent treatment of multiple patients. Some happened long ago; some are ongoing. The sanctioned doctors were paid anywhere from $100 to more than $140,000.

Several doctors were disciplined for misconduct involving drugs made by the companies that paid them to speak. In 2009, Michigan regulators accused one rheumatologist of forging a colleague’s name to get prescriptions for Viagra and Cialis. Last year, the doctor was paid $17,721 as a speaker for Pfizer, Viagra’s maker.

A California doctor who was paid $950 this year to speak for AstraZeneca was placed on five years’ probation by regulators in 2009 after having a breakdown, threatening suicide and spending time in a psychiatric hospital after police used a Taser on him. He said he’d been self-treating with samples of AstraZeneca’s anti-psychotic drug Seroquel, medical board records show.

Other paid speakers had been disciplined by their employers or warned by the federal government. At least 15 doctors lost staff privileges at various hospitals, including one New Jersey doctor who had been suspended twice for patient care lapses and inappropriate behavior. Other doctors received FDA warning letters for research misconduct such as failing to get informed consent from patients.

Pharma companies say they rely primarily on a federal database listing those whose behavior in some way disqualifies them from participating in Medicare. This database, however, is notoriously incomplete.

The industry’s primary trade group says its voluntary code of conduct is silent about what, if any, behavior should disqualify physician speakers.

“We look at it from the affirmative—things that would qualify physicians,” said Diane Bieri, general counsel and executive vice president of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

Some physicians with disciplinary records say their past misdeeds do not reflect on their ability to educate their peers.

Family medicine physician Jeffrey Unger was put on probation by California’s medical board in 1999 after he misdiagnosed a woman’s breast cancer for 2½ years. She received treatment too late to save her life. In 2000, the Nevada medical board revoked Unger’s license for not disclosing California’s action.

As a result, Unger said, he decided to slow down and start listening to his patients. Since then, he said, he has written more than 130 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters on diabetes, mental illness and pain management.

“I think I’ve more than accomplished what I’ve needed to make this all right,” he said. During 2009 and the first quarter of 2010, Lilly paid Unger $87,830. He said he also is a paid speaker for Novo Nordisk and Roche, two companies that have not disclosed payments.

The drug firms, Unger said, “apparently looked beyond the record.”

Companies make their own experts

Last summer, as drug giant Glaxo battled efforts to yank its blockbuster diabetes drug Avandia from the market, Nashville cardiologist Hal Roseman worked the front lines.

At an FDA hearing, he borrowed David Letterman’s shtick to deliver a “Top Five” list of reasons to keep the drug on the market despite evidence it caused heart problems. He faced off against a renowned Yale cardiologist and Avandia critic on the PBS NewsHour, arguing that the drug’s risks had been overblown.

“I still feel very convinced in the drug,” Roseman said with relaxed confidence. The FDA severely restricted access to the drug last month citing its risks.

Roseman is not a researcher with published peer-reviewed studies to his name. Nor is he on the staff of a top academic medical center or in a leadership role among his colleagues.

Roseman’s public profile comes from his work as one of Glaxo’s highest-paid speakers. In 2009 and 2010, he earned $223,250 from the firm—in addition to payouts from other companies.

Pharma companies often say their physician salesmen are chosen for their expertise. Glaxo, for example, said it selects “highly qualified experts in their field, well-respected by their peers and, in the case of speakers, good presenters.”

ProPublica found that some top speakers are experts mainly because the companies have deemed them such. Several acknowledge that they are regularly called upon because they are willing to speak when, where and how the companies need them to.

“It’s sort of like American Idol,” said sociologist Susan Chimonas, who studies doctor-pharma relationships at the Institute on Medicine as a Profession in New York City.

“Nobody will have necessarily heard of you before—but after you’ve been around the country speaking 100 times a year, people will begin to know your name and think, ‘This guy is important.’ It creates an opinion leader who wasn’t necessarily an expert before.”

To check the qualifications of top-paid doctors, reporters searched for medical research, academic appointments and professional society involvement. They also interviewed national leaders in the physicians’ specialties.

In numerous cases, little information turned up.

Las Vegas endocrinologist Firhaad Ismail, for example, is the top earner in the database, making $303,558, yet only his schooling and mostly 20-year-old research articles could be found. An online brochure for a presentation he gave earlier this month listed him as chief of endocrinology at a local hospital, but an official there said he hasn’t held that title since 2008.

And several leading pain experts said they’d never heard of Santa Monica pain doctor Gerald Sacks, who was paid $249,822 since 2009.

Neither physician returned multiple calls and letters.

A recently unsealed whistleblower lawsuit against Novartis, the nation’s sixth-largest drug maker by sales, alleges that many speakers were chosen “on their prescription potential rather than their true credentials.”

Speakers were used and paid as long as they kept their prescription levels up, even though “several speakers had difficulty with English,” according to the amended complaint filed this year in federal court in Philadelphia.

Some physicians were paid for speaking to one another, the lawsuit alleged. Several family practice doctors in Peoria, Ill., “had two programs every week at the same restaurant with the same group of physicians as the audience attendees.”

In September, Novartis agreed to pay the government $422.5 million to resolve civil and criminal allegations in this case and others. The company has said it fixed its practices and now complies with government rules.

Roseman, who has been a pharma speaker for about a decade, acknowledged that his expertise comes by way of the training provided by the companies that pay him. But he says that makes him the best prepared to speak about their products, which he prescribes for his own patients. Asked about Roseman’s credentials, a Glaxo spokeswoman said he is an “appropriate” speaker.

Getting paid to speak “doesn’t mean that your views have necessarily been tainted,” he said.

Plus pharma needs talent, Roseman said. Top-tier universities such as Harvard have begun banning their staffs from accepting pharma money for speaking, he said. “It irritates me that the debate over bias comes down to a litmus test of money,” Roseman said. “The amount of knowledge that I have is in some regards to be valued.”

ProPublica Director of Research Lisa Schwartz and researcher Nicholas Kusnetz contributed to this report.