gpointstudio/Shutterstock

This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

If you’re like me, you writhe in guilt-ridden anguish each time you forget to bring your canvas tote to the grocery store. But in the rare times we do remember our reusable bags, Americans tend not to think much about what we actually put inside them, according to a new survey. The takeaway: We waste a lot of extra food (and money) simply because we don’t shop often enough.

As big of a problem as it is, food waste rarely makes the news. There was some buzz a while back about France’s ban on grocery stores throwing out edible food, but the numbers show that this is only a small part of the problem. Americans vastly underestimate their own food waste, which turns out to be driven mostly by a desire to avoid getting sick—even though saving money is also a top priority. That means we end up stocking our shelves with more than we need to ensure we’ll always have something fresh when we want it.

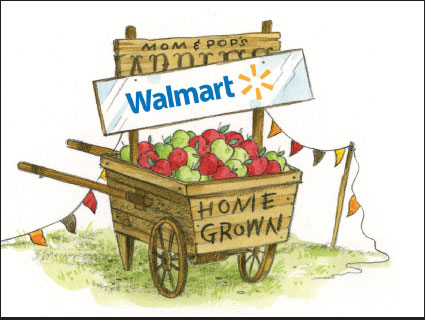

That sort of behavior is encouraged at bulk stores like Costco and Walmart, which operate on the myth that buying in bulk helps you save money. But new evidence shows that the push for huge quantities of cheap, high-quality food has caused us to be more wasteful than ever. Simply put: We’re throwing away more in food waste than we are saving by buying in bulk.

“People almost entirely neglect the cost of the food they’re throwing away from their kitchen,” says Victoria Ligon of the University of Arizona, who led the new study. “If you throw away a meal because you’ve eaten out when you weren’t planning to, the cost of that restaurant meal is higher than you think. People don’t account for that at all.”

Ligon’s study examined shopping patterns of several households through in-depth interviews and food diaries. The results found that people are generally too ambitious in their grocery shopping—buying ingredients for meals days or weeks in advance—when our brains and appetites are hard-wired for little more than the next meal. Our lives get busy, we may schedule a few impromptu evenings out with friends, and suddenly we have a pile of furry cucumbers at the bottom of the fridge. As most people who have ever cooked a meal know, planning meals days in advance is almost impossible.

“Every single person I talked to in my study felt very uncomfortable at the idea of throwing away food,” says Ligon. “We have very strong norms in our culture around not wasting.” But Ligon says people shouldn’t feel guilty: “This is not a problem that stems from individual apathy. It’s a structural problem.”

The bulk stores know this—their whole business model is to trick us into buying more than we need, and all the better if the food seems healthy and good for the planet. During a green push several years ago, Walmart became the biggest grocery store chain in the country. In May, Costco—that wonderland of 9-pound cases of bison jerky and terrier-sized tubs of licorice—became the leading purveyor of organic grocery items, dethroning Whole Foods. Walmart’s Sam’s Club stores, which operate on a similar membership-based, it-takes-two-people-to-push-a-cart style of warehouse retail, is reportedly moving in a similar direction and greatly expanding its organic offerings. Organic food is becoming big business, at least partly because stores are able to charge higher markups.

Which brings us back to food waste. As much as 40 percent of America’s food supply gets thrown away every day, with perishable items like dairy, breads, meats, fruits, and vegetables leading the way. The total annual bill of food waste for consumers is a whopping $162 billion, which works out to about $1,300 to $2,300 per family per year. Clearly, that much food could feed a lot of people who otherwise go hungry.

But even that huge sum doesn’t factor in knock-on effects: Wasting food means we’re throwing away money, but we’re also throwing away 35 percent of the nation’s fresh water supply and 300 million gallons of oil each year. That makes tackling food waste the low-hanging fruit amid growing concern over drought and climate change. Next to paper and yard trimmings, food takes up the biggest share of the nation’s landfills—and contributes about 20 percent of the country’s methane emissions.

Ligon thinks she’s found the start of a solution: Just shop more often.

“When you’re talking about food, feeling really plays a big role. Things like predicting how hungry you are, your appetite, and what you’re in the mood for—in the future—turn out to be very challenging,” Ligon says. “If you’re shopping more frequently, you can purchase food that is meant to be eaten in a shorter time frame.”

But there’s a catch. Ligon’s research also revealed that people regularly buy groceries from three to seven different stores. With so many choices, there’s an incentive to overbuy at each stop—especially if you don’t plan on being back for a few days. We’ve all done this: You go into Trader Joe’s planning to buy some nectarines, and you come out with an armful of specialty potato chips and four frozen pizzas.

Ligon says same-day food delivery services like AmazonFresh (which charges $299 per year for free deliveries over $50 and provides you with a magic wand by which you can place your orders) and soon-to-emerge smartfridges that suggest recipes for you based on your food that’s about to go bad (like this one Samsung showcased in 2013) might be among the most promising ways to cut down on waste, with big rewards in water, energy, and climate change—and money.

After all, you can’t waste what you don’t buy in the first place.