<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=343025852&src=id">Malachy666</a>/Shutterstock

When you’re looking for dinner ingredients at the supermarket, you probably wince at the bruised pears, skip over those oddly shaped carrots, and reach past ugly red peppers. This preference for pretty produce means the ugly fruits and vegetables are tossed out, filling landfills with otherwise nutritious food. A study found that in 2010, more than 11 million pounds of food from supermarkets and restaurants went uneaten.

Food waste—from grocery stores, restaurants, and households across the country—is becoming a buzzword, and not just for foodies. It’s estimated that 40 percent of the food in the United States won’t end up in people’s stomachs, costing Americans $165 billion a year. The Ad Council (the same group that came up with the Crash Test Dummies for wearing seatbelts and Smokey Bear for wildfire prevention) just rolled out “Save the Food” as its latest public-service campaign. And earlier this month, celebrity chefs met in Washington to speak with Congress about the Food Recovery Act—legislation that aims to curb food waste from farms and restaurants.

Meanwhile, crafty entrepreneurs are repurposing and repackaging leftover materials into new products. A recent event in the Bay Area gave me insight into what some techies are doing, making, and growing to fight food waste.

That six-pack of IPA you enjoyed on Friday night generated about a pound of waste in its making. After brewers soaked barley (or sometimes other grains) in hot water and extracted the liquid to make beer, they’re left with a lot of spent grain on their hands. Most rural breweries, like Northern California’s Lagunitas or Sierra Nevada, haul the byproduct to nearby farms, which feed the grain to their animals. Others recycle it as compost. But for smaller breweries in urban areas, miles away from hungry pigs, figuring out what to do with the leftovers isn’t always easy.

The company Regrained turns that spent grain into snack bars. At a Meetup event in the Mission district of San Francisco, curious eaters lined up around the company’s booth, intrigued by the displayed logo “Eat Your Beer.” Cameron Schwartz, a tall man wearing a T-shirt with the same words, explained how his brother and buddies—all home-brewers—decided to open a business that takes beer byproducts and bakes them into bars, costing $2.50 a pop and sold at local grocery stores. So far, ReGrained has worked with three breweries in the Bay Area.

“It’s been really nice working with ReGrained to see an actual, viable product from something we were essentially throwing away,” said Phil Meeker of Triple Voodoo Brewery in a video from the ReGrained website. ReGrained’s founders say they want to eventually bake cookies, cereals, and chips with the spent grains. And to everyone wondering: No, you can’t get buzzed off that honey almond IPA or coffee chocolate stout bar.

A byproduct that ends up in landfills from America’s other favorite beverage? Soggy coffee grounds. BTTR (Back to the Roots) Ventures, another company at the meetup, has gained notoriety for its products that start from coffee grounds (which are actually nutritious). Using the mushy grounds as soil, BTTR Ventures harvests a variety of mushrooms and sells them at local farmers markets and grocery stores. The idea came to them from women doing something similar in East Africa and South America. The company has expanded to sell garden-in-a-can cilantro and basil plants, stone ground cereal, and ready-to-grow garden kits.

Next to BTTR Ventures’s stacked cans were wooden boxes brimming with smaller-than-average apples—all produce that was deemed too ugly to sell in supermarkets. Imperfect buys oddly shaped produce from farmers who can’t sell it elsewhere, and then delivers it to members’ doorsteps, much like a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program. (You may have heard about the company from a National Geographic feature earlier this year.)

Aleks Strub, Imperfect’s director of marketing, held up a petite apple and an oblong one. “It’s a tiny apple or a big apple or an apple with just the tiniest scar,” she explained. “It’s perfectly edible and delicious but we are throwing it away, whether it be in a landfill or to feed animals, but not to feed people.” Imperfect delivers over 2,000 boxes of this ugly produce each week, equating to about 15 tons of recovered food.

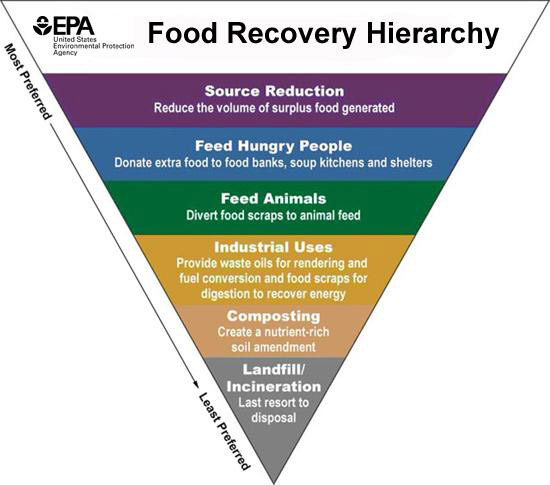

So are these innovative products the solution to fighting excess at a national scale? Probably not. The Environmental Protection Agency ranks different methods of reducing food waste in an inverted pyramid graphic. The top and most important step is making sure it doesn’t happen in the first place. Next ranks feeding the hungry with any excess food. The practice of reusing organic materials ranks toward the bottom—not the best way, but surely a step in the right direction to changing the statistics that the American family wastes between $1,365 to $2,275 worth of food and beverages each year.

As I browsed the innovative companies featured at the meetup, I wondered: With the packaging and production of cans for gardening, the plastic wrap on the beer snack bars, and the marketing materials involved in starting a business, do these food waste fighters have the potential to create more waste than they salvage?

To prevent such a fate, Darby Hoover, a senior resource analyst at the National Resources Defense Council, encourages the companies to minimize wrappers and boxes wherever possible. “The common-sense approach is rather than compare the packaging or product, it’s just follow general principles that minimize packaging at all,” she said.

Though I’m betting someone will figure out how to make spent-barley or coffee-ground wrappers next. Now that’s a concept I can get behind.