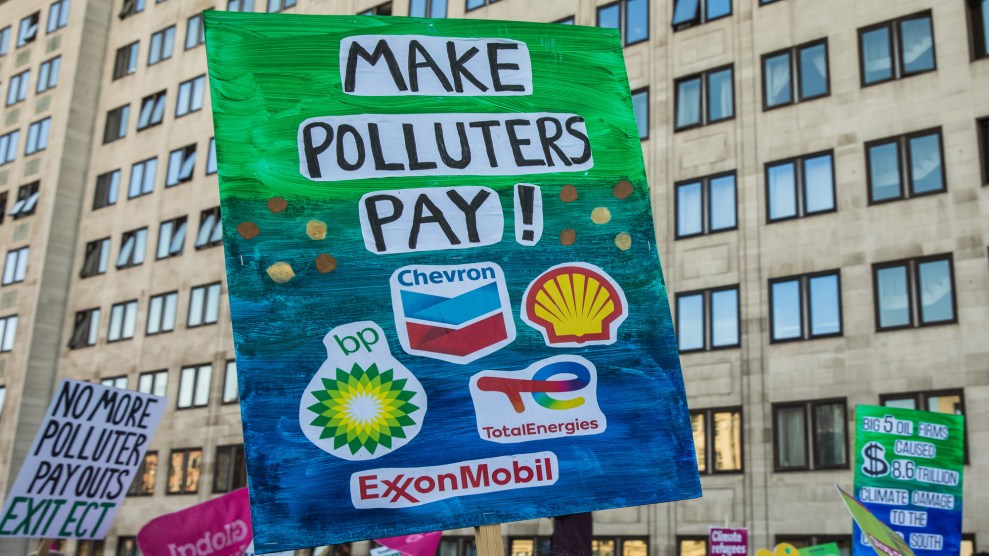

Student activists from Fridays for the Future join Earth Day rally and march to the White House on April 22.Kevin Wolf/AP

This was a historic week for climate litigation. Tuesday marked the closing arguments in Held v. Montana, a lawsuit brought by sixteen young people arguing that the state’s fossil fuel friendly legislation is at odds with an environmental rights clause in the Montana constitution. It’s only the third climate-related lawsuit to go to trial, and the first lawsuit focusing on a state’s constitution.

“There have been hundreds of lawsuits but very few of them go to trial,” says Michael Gerrard, the founder and faculty director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University.

The lawsuit, which was filed in 2020, hinges on a section of the state constitution that affirms the right to a clean environment: “The state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations.” As the trial date neared, lawmakers repealed a 30-year-old pro–fossil fuel law; the state Attorney General Austin Knudsen followed up by seeking to dismiss the parts of Held that mention it. In the end, the law’s repeal did little to stop the case. The Montana Petroleum Executive Director went on record saying that the repeal “will not have any effect on energy policy moving forward.” And as the lawyers for the plaintiffs, who were all under 18 when the lawsuit was filed, pointed out, there are plenty of other fossil fuel friendly laws on the books, including one that bars climate change considerations in environmental assessments of industry projects. The youth plaintiffs are challenging those pieces of legislation in particular.

“The world is burning,” testified Claire Vlases, the 20-year-old plaintiff from Bozeman, Montana. “That sounds like a dystopian horror film, but it’s not a movie. It’s real life. That’s what us kids have to deal with.” The plaintiffs’ expert witness Anne Hedge agrees. In her testimony, the Montana Environmental Information Center co-director accused the state government of “running in the wrong direction to address the climate crisis.”

To better understand the strategy behind the lawsuit and how it might impact future climate litigation, I talked to Gerrard, a practicing environmental lawyer with 40 years of experience and 14 books under his belt. You can read our 30-minute conversation, edited and condensed for clarity, below.

So this case hinges on Montana having an environmental rights clause in the constitution, how common are those?

Most of them were enacted in the early 1970s, which was the era when most of the US environmental laws were enacted. New York just added one two years ago, but most of them are very old, and most of them haven’t been used much. There was an important decision under Pennsylvania’s environmental rights clause around 2013 declaring unconstitutional a state law that barred localities from regulating fracking. That decision garnered a great deal of attention and revisited interest in state constitutional environmental rights. These provisions are still very much the exception, not the rule—only a handful of states have environmental clauses written into their constitutions. Though as it happens, in September, a trial is scheduled in Hawaii based on that state’s environmental clause.

And how are the Montana and Hawaii cases different than past climate change lawsuits?

A much larger number of cases were brought under something called the public trust doctrine. In 1970, a law professor named Joseph Sax from the University of Michigan wrote a famous article about how the public trust doctrine [which holds that the state has a responsibility to protect natural resources for future generation] could be used for environmental protection. And a law professor at the University of Oregon, Mary Wood, wrote that the public trust doctrine applies to the atmosphere and could be used to fight climate change. A nonprofit group formed in Oregon called Our Children’s Trust began bringing lawsuits all over the country based on the public trust doctrine. These lawsuits were dismissed on various legal grounds, except for the Juliana v. US, which advanced significantly until it was thrown out by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But, it may now be coming back.

That was a suit brought by 21 young people in Oregon against the federal government, seeking an order that the federal government prepare and implement a program to passively reduce greenhouse gas emissions and draw excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The trial went back and forth several times to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But ultimately in January 2020, by a two-to-one vote, they dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that it was not the role of the courts to set climate policy; it should be left to the elected branches. The court accepted the climate science that had been presented by the plaintiffs and acknowledged that climate change is a grave threat. But they said it’s not their job to address. The plaintiffs then asked the court for permission to amend their complaint to ask for more mild relief—just a declaration of rights. And about three weeks ago, the court granted that motion. We’re now waiting to see what stance the Biden Department of Justice takes toward that motion.

Our Children’s Trust also played a central role in the Montana case. What’s distinctive about this case in Montana is that it’s brought under the environmental rights clause of a state constitution. That has given it much more force.

Wow. There’s a lot going on. In terms of climate law, both the Montana case and the Juliana case.

Let me also mention the degree to live activity internationally. A group of young law students in the Pacific persuaded Vanuatu, one of the endangered island states, to ask the United Nations General Assembly to pose a question about climate change to the International Court of Justice in the Hague. That led to a very successful campaign; about two months ago, the UN General Assembly voted by consensus to send this question to the International Court of Justice. Also, there are several climate change cases now pending before the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France, and before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in San Jose, Costa Rica, and a climate petition pending before the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea. Our center maintains a database of all the climate change cases in the world and there have been 2200 climate change cases that have been brought, of which about 70 percent are in the US. It’s a rapidly growing field.

Jumping back to the Montana case. There’s been a lot of backlash from lawmakers in Montana against this lawsuit. Is the potential outcome of this case an inroad into addressing that or is that just a completely separate legislative fight?

That’s a separate legislative and political fight. I don’t know whether there will be an effort to repeal the environmental rights clause of the constitution. But that sort of thing is often very challenging. No environmental rights clause has ever been repealed.

The defense just wrapped up their evidence, and we’re waiting on the ruling. What would be the ramifications of potential rulings?

Well, as a technical matter, the court would not set a binding precedent, because it’s just a trial-level court in Montana. But a successful ruling for the plaintiffs could be very energizing to young people and climate activists and lawyers around the country and indeed, around the world. These cases are being closely followed and success here could lead to similar efforts in other places. It could embolden other judges to move in similar directions.

If the judge strikes down on the case, what do you think will happen to the larger climate law movement? Do you think that that will affect future rulings?

It would depend on the grounds that the court used. If the court were to reject the lawsuit on fairly narrow issues of Montana procedural law, that would be very limited in its impact. If this judge said she didn’t believe the climate science that was presented by the plaintiffs, that would be more damaging. The state has raised that emissions from Montana are so small that it wouldn’t make any difference if they stopped the emissions. If the court were to agree with that, it would be harmful because most states and most countries have relatively small emissions.

Do you have any final takeaways from the case?

One is that I thought that the plaintiff’s lawyers did a wonderful job structuring and presenting the case. The young people were very moving and convincing when they told their personal stories. And, most of the expert witnesses were from Montana and were able to bring the case home. They showed the impacts of climate change on Montana. I thought that was extremely well done. I was surprised that [the state of] Montana chose to withdraw its only scientific witness. They clearly concluded that downplaying the impacts of climate change would not be a winning strategy in the face of the overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary.

One other thing I would say is that national governments, parliaments, and presidents around the world have uniformly failed to act adequately on climate change, leading many people to resort to the courts. So I think this trend of more climate litigation is going to continue. But no one should think that litigation is the silver bullet. It can be one important tool in the toolkit.