The Endangered Species Act has been one of the country’s most valuable environmental tools, but it faces new threats. As the law turns 50, we’re asking whether this “pit bull” of an environmental law, as one expert described it, can survive the challenges of our time—from political attacks to climate shocks. You can read all the stories here.

For one species of snow-dwelling weasel, Christmas came early this year. After nearly 30 years of waiting, the North American wolverine will be listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, the Biden administration said in late November, citing habitat fragmentation and the “increasing impacts” of climate change.

Conservationists applauded the decision—which allows the government to step in to help the wolverine recover—but with more of a slow clap than a roaring ovation. Environmental groups had originally brought the wolverine’s decline to the attention of the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as early as 1994, but the agency flip-flopped on its decision for decades. In November, it officially sided with the wolverine. “They just kind of turned around in all the issues that were important,” wolverine scientist Jeff Copeland told Inside Climate News. “I’m just really curious as to what happened.”

One explanation is the emergence of new data. “The wolverine’s adapted and has evolved in cold, snowy conditions,” FWS biologist Jesse D’Elia told the New York Times. “As these conditions continue to change in the Western US, the outlook for wolverines is less secure than we found in our previous assessments.” But other experts, including one federal judge, say the delay may have been a result of “political pressure” by Western state governments, where a listing may impact the snowmobiling and fossil fuel industries.

For many species, it’s a familiar story. Due to a variety of reasons, including insufficient funding, bureaucracy, and a lack of political will, environmental advocates say, the process of listing a species can often take more than a decade.

By law, when a third party (say, a scientist or an environmental group) petitions FWS to list a species, a decision should take no longer than two years. But if FWS initiates the process itself, it doesn’t have any sort of timeline until it publishes a proposed ruling to list. Noah Greenwald, the endangered species director at the Center for Biological Diversity, calls this a loophole of sorts, because it allows species to languish for decades, even when the FWS has said the plant or animal might be at risk of extinction.

These delays can be—and this is no exaggeration—existence-ending. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, at least 47 species have gone extinct while waiting for protection under the ESA. And hundreds of species are still waiting: As of April, more than 300 species sit on the federal government’s “workplan” for listing or designating habitat protections.

Part of the problem, according to Greenwald, is that listing decisions often include “multiple layers” of review; he attributes the agency’s foot-dragging to caution and “fear of political backlash.” Other experts tell me, generally, the agency is full of many well-intentioned biologists, but is short on cash. “At the end of the day,” said Andy Mergen, an environmental law professor at Harvard University, “they can only do what Congress has funded them to do.” When I asked FWS what caused the wait, a spokesperson told me, “Endangered species recovery is complex and difficult work, often requiring substantial time and resources.”

To give you a sense of what that backlog looks like for plants and animals in the United States and around the world, here’s a sample of 15 species that waited more than a decade for protection, went extinct while waiting, or are still in line. Where possible, we included explanations for why the listings took so long.

The good news is, for most species that are granted an all-powerful listing, the law works: The ESA has prevented extinction for 99 percent of listed species, which currently includes more than 720 animals and 930 plants, both endangered (at risk of extinction) and threatened (at risk of becoming endangered). It’s, as FWS Director Martha Williams said earlier this year, “a safety net that stops the journey toward extinction.”

But, as you’ll see below, delaying the deployment of that safety net may put a full recovery out of reach. In the case of the wolverine, conservationists worry its listing arrived too late. “They might not make it,” Western Environmental Law Center attorney Matthew Bishop reportedly said after November’s announcement. “But let’s give them the best shot we can.”

Species that Waited a Long, Long Time for Protection

Canada lynx

Lynx canadensis

As its name suggests, the Canada lynx primarily lives in the cold, snowy forests of Canada, but has also been spotted in Maine, Montana, Washington, and Colorado. It prefers to dine on the snowshoe hare, but will also eat rodents and birds, keeping these populations in check—a much-needed service for the health of the ecosystem. Habitat fragmentation, poaching, and rising global temperatures pose some of the biggest threats to the lynx, which sat in listing limbo for many years due to a lack of “substantial information” about its status, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Wait time: 22 years, 8 months

Alabama sturgeon

Scaphirhynchus suttkusi

An “opportunistic bottom feeder,” the Alabama sturgeon eats bugs, plants, and mollusks in the murky waters of the Alabama River and the lower Cahaba River. In the late 1800s, commercial fishermen reported harvesting tens of thousands of pounds of Alabama sturgeon per year. But now, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service, this species is “one of the rarest and most endangered fish in the nation”—and may be close to extinction. (In 1994, the Service determined there was “insufficient information” that the fish “continued to exist,” but renewed considerations in 1997 after the species was rediscovered in Alabama.)

Wait time: 17 years, 4 months

Florida bonneted bat

Eumops floridanus

“Though often feared and loathed as sinister creatures of the night,” FWS says, “bats are vital to the health of our environment and our economy.” They are master insect-eaters, consuming so many bugs that they save US farmers more than $3 billion per year in estimated crop damage and pesticide costs. Poop samples indicate that the Florida bonneted bat—named for its large, conjoined ears—typically eats a variety of beetles, flies, and moths. In 2011, faced with a backlog of hundreds of species petitions (and several lawsuits over it), the Obama administration announced a six-year “work plan” to address its mountain of protection requests, including for the Florida bonneted bat. The species was listed two years later.

Wait time: 28 years, <15 days

Behren's silverspot butterfly

Speyeria zerene behrensii

This pollinator species once ranged across Northern California, from Sonoma to Mendocino counties. But in 2020, officials counted no Behren’s silverspot butterflies in their annual survey. “Looking week after week for butterflies, and not seeing them and not seeing them,” one biologist told High Country News, “it’s disheartening and scary.” Biologists are now working to reintroduce the species to its native habitat.

Wait time: 9 years, 7 months

Santa Cruz cypress

Cupressus abramsiana

Like all trees, the Santa Cruz cypress sequesters carbon, prevents soil erosion, and provides a habitat for other species, like birds and insects. After the Smithsonian identified the tree as a species of concern in 1975, bureaucratic dithering meant it took 10 years for FWS to decide a listing was “warranted, but precluded” by other, more urgent requests. When the tree was finally listed in 1987, scientists estimated there were only about 2,300 of these trees left, located in five groves in the Santa Cruz Mountains. In 2016, after officials determined the five populations were secure, the government downlisted the species from “endangered” to “threatened,” a move celebrated by environmental advocates.

Wait time: 12 years, 0 months

Species Currently Waiting for Protection

Western bumblebee

Bombus occidentalis

If you eat fruits or vegetables, you have bees to thank: According to the US Geological Survey, “North America’s ~4500 native bees, including the western bumblebee, are among the most effective pollinators and most of the fruits and vegetables in our grocery stores are pollinated by them.” Once one of the most common bees in North America, the Western bumblebee has seen its population drop by more than 30 percent due to disease, pesticide use, habitat loss, and climate change. In 2020, the Center for Biological Diversity sued the Trump administration over the delayed protections for 241 species, including the Western bumblebee, arguing that the government “consistently failed” to meet its own deadlines.

Wait time: 8+ years

Alabama hickorynut

Obovaria unicolor

The “invisible engineers of our aquatic ecosystems,” freshwater mussels keep streams clean by filter feeding, and serve as “indicator species” for water quality. (Freshwater mussels also have some of the most interesting sex lives of the animal kingdom; some reproduce by disguising parts of their bodies as “bait,” luring in unsuspecting fish, and then infecting the fish with parasitic larvae.) With more than 70 percent of all freshwater mussels in decline and at least 35 species declared extinct, this animal is the most imperiled group of organisms in the country, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. “Scientists around the world are sounding the alarm about the extinction crisis, but the Trump administration can’t be bothered to lift a finger for hundreds of species that are in serious trouble,” the Center's Noah Greenwald said in 2019, when the group sued the Trump administration over the Alabama hickorynut and more than 270 other species with delayed decisions. “Every day protections are delayed is a day that moves these fascinating species closer to extinction.”

Wait time: 13+ years

Red tree vole

Arborimus longicaudus

Tree voles are like forest rats: small rodents less than eight inches long, with fur-covered tails. Unlike other voles, the red tree vole lives in—you guessed it—trees, but particularly enjoys the Douglas fir. The vole, according to the Bureau of Land Management, serves as "important prey" for the threatened northern spotted owl, among other owl species. Because the vole prefers to live in old-growth trees, its biggest threats are logging and habitat fragmentation. In 2011, the service determined the vole’s status “warranted” protection, but its listing was put on the back burner while the agency focused on other, higher-priority species. The Trump administration removed the vole from consideration in 2019; conservationists then sued, and the agency is currently reconsidering its decision.

Wait time: 16+ years

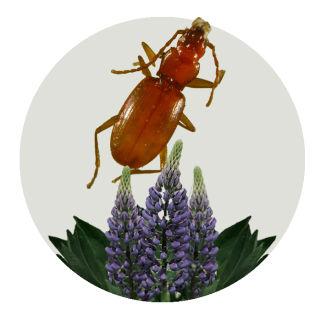

Overlooked cave beetle

Pseudanophthalmus praetermissus

We see you, overlooked cave beetle! Like many cave beetles, this species can’t see or fly, but it can hunt: According to the National Speleological Society (i.e., cave enthusiasts), which named Pseudanophthalmus cave beetles the 2021 “Cave Animal of the Year,” cave beetles are “one of the top predators in terrestrial cave ecosystems”—feeding on all sorts of insects, including worms and millipedes. In turn, the beetles serve as food for salamanders, crayfish, and other larger predators. So few animals reside in caves to begin with, according to the National Park Service, that many are endangered. “All species in the cave system are dependent upon each other for survival.”

Wait time: 34+ years

Cascade Caverns salamander

Eurycea latitans

As a species dependent on clean water to survive, the Cascade Caverns salamander is an “indicator of declining groundwater and water quality,” according to the Center for Biological Diversity, and lives in the salamander hotspot of Texas’ Edwards Plateau. But urban sprawl, drought, and water pollution are driving this species toward extinction. The center included the salamander in the same 2019 mega-lawsuit as the Alabama hickorynut (and more than 270 other species, see above) that accused the Trump administration of “hostility toward wildlife.”

Wait time: 40+ years

Species That Have Gone Extinct While Waiting for Protection

Tacoma pocket gopher

Thomomys mazama tacomensis

Although considered pests by some farmers, pocket gophers play a “key role” in aerating soils and stimulating plant growth, according to FWS. Almost all of this subspecies’ habitat has been replaced by residential or commercial development, the agency says, including a large golf course. Before the government declared its extinction, scientists conducted “extensive surveys” looking for the pocket gopher in the 1970s, the 1990s, and 2011, with no luck.

Wait time before extinction: 11 years, 1 month

Bishop's ʻōʻō

Moho bishopi

Endemic to Hawaii, the Bishop's ʻōʻō was a loud species of black and yellow honeycreeper. Like hummingbirds, many honeycreepers are nectar-eaters and key pollinators, including the Bishop's ʻōʻō, which enjoyed slurping up lobelia flower nectar. Scientists don’t know much about this species, including its major threats, but according to the state of Hawaii, that list likely included disease and hunting. “The bird’s vocalizations have been described as varied and ‘unlike any other native bird.’”

Wait time before extinction: 17 years, 4 months

Stephan's Riffle Beetle

Heterelmis stephani

As far as we know, Stephan’s riffle beetle lived in just two locations in Arizona: Bog Springs Campground and Sylvester Spring in Madera Canyon. Rifle beetles gobble up decaying plant material, and therefore play an important role in maintaining dissolved oxygen in the water, making them a good indication of water quality. According to the government, the Stephan's riffle beetle population “may have started declining when water from springs in Madera Canyon was first captured in concrete boxes and piped to divert water for domestic and recreational water supplies.” It hasn’t been seen since 1993, prompting the Obama administration to declare it extinct. “The extinction of species, tiny and tremendous alike, leaves us all a little poorer, whether we recognize the losses or not," the Center for Biological Diversity’s Michael Robinson said at the time.

Wait time before extinction: 12 years, 4 months

Guam white-throated ground dove

Gallicolumba xanthonura xanthonura

In 1979, when the government of Guam petitioned the US government to list the white-throated ground dove as an endangered species, less than 100 birds remained on the island, the majority of the population lost to introduced brown tree snakes, “increased urbanization,” illegal hunting, and the use of defoliants, or toxic herbicides, during WWII, among other threats. In fact, nearly all of Guam’s native birds have disappeared, which scientists say may have caused the island’s spider population to soar and forests to thin out. (Without birds, there is little seed dispersal.) “There’s a concern that [Guam’s forests] may become filled with open areas and start to look more like Swiss cheese than a closed canopy forest,” one scientist told Smithsonian in 2013.

Wait time before extinction: 9 years, 7 months

Beaverpond marstonia

Marstonia castor

If you’ve ever had a fish tank, you’ve likely seen the benefit of snails, which work to clean up algae, dead plants, and other pollutants in freshwater ecosystems. This tiny, freshwater snail was the first species to be listed as extinct under the Trump administration, though its decline had been in the works for decades. In 2016, the Center for Biological Diversity sued the government, prompting federal biologists to search for the snail in its only known habitat: three creeks in Georgia near Lake Blackshear. Though they detected none, some scientists are still looking for the snail. “It’s heartbreaking to lose wildlife to extinction, especially when timely intervention could have saved the species,” Tierra Curry, a scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity said in 2017, when the snail was declared extinct, accusing FWS of “shirking their responsibility to prevent irreplaceable wildlife from being lost forever.”

Wait time before extinction: 33 years, 7 months

Data provided to Mother Jones by the Center for Biological Diversity; Environmental Conservation Online System, Fish and Wildlife Service.

Data visualizations by Michael Johnson and Adam Vieyra.

Photo credits

Alabama hickorynut: Jeff Garner/iNaturlist

Alabama sturgeon: Patrick O’Niel/Geological Survey of Alabama/USGS

Beaverpond marstonia: Robert Herschler/Smithsonian

Behrens silverspot butterfly: Asa Spade/iNaturalist

Bishop's ʻŌʻŌ: Wikimedia

Canada lynx: Sylvain Cordier/Gamma-Rapho/Getty

Cascade Caverns salamander: Tom Devitt/University of Texas

Florida bonneted bat: Walter Michot/TNS/Zuma

Guam white-throated ground dove: Wikimedia

Overlooked cave beetle: USFWS

Red tree vole: Janice Reid/iNaturalist

Santa Cruz cypress: John Rusk/wikimedia

Stephans rifle beetle: USFWS

Tacoma pocket gopher: Kim Flotlin/USFWS

Western bumblebee: Damien Meyer/AFP/Getty