Flood debris in Studio City, Southern California, Feb. 5, 2024. Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The storm raged over California for more than five days. As the powerful atmospheric river made landfall, furious winds and torrential downpours ripped trees from their roots, turned streets into rivers and sent mud cascading into homes.

Along with chaos, the storm brought opportunity. Scientists were ready, on land and in-flight, to deploy instruments that measure atmospheric rivers like this one. They released tools from planes, equipped with small parachutes, or floated them up from the ground attached to balloons, directly into the storm’s path.

These small but mighty devices provide key intelligence that will help improve weather forecasts as the climate crisis makes already powerful storms more dangerous.

Atmospheric rivers have long been important features of weather systems across the US west and are vital to replenishing the state’s reservoirs and snowpack. But filled with enough moisture to rival flows at the mouth of the Mississippi—and often many times more—the strong systems that carry water across the Pacific also often cause the most destructive floods.

Warming oceans are supercharging the storms, making them deadlier and costlier. Last week’s storms killed nine people, caused an estimated $11 billion in damage and economic loss, and dumped half of Los Angeles’s annual rainfall on the city in a matter of days.

Now, scientists are racing to better understand these systems before they get worse. The work is greatly expanding the accuracy of weather predictions, giving water managers more time to plan and communities earlier warnings to prepare, long before overhead clouds darken, but there’s far more to learn about these systems, especially as the dangers from them grow.

Research into these airborne plumes of water vapor pulled from the tropical Pacific has grown dramatically in the three decades since “atmospheric rivers” got their name. But forecasts of where a storm will make landfall can still be off by hundreds of miles, and it’s difficult to predict how particular storms will play out.

Scientists are working to make sense of the layered and complicated conversations that happen among the ocean, the atmosphere and the land, and are hoping to gain stronger insights on how, when and where storms will strike.

“The more we learn, the more we recognize we need more data about this,” said Maike Sonnewald, the leader of the computational climate and ocean group at University of California-Davis.

Sonnewald, an oceanographer who uses computer science to gain insights about the climate and long-range weather forecasts, added that recent advances in the satellite age helped paint a picture of how the ocean and the atmosphere interact. That picture, metaphorically speaking, still has too few pixels.

“We don’t necessarily have a high-enough resolution to be able to model specific things,” she added, explaining that the dynamic nature of the ocean—and how easily small shifts can create big changes in the models—pose predictive challenges.

“The climate is changing—we are making the earth hotter—and that is known. It is the details that are hard to discern,” Sonnewald said. A warming atmosphere can hold exponentially more water vapor and heating ocean-surface temperatures will evaporate more quickly, so scientists can easily predict how things will worsen. It’s trickier to know when and where.

In the days before the storm hit, it was clear that it was going to pack a punch. As it swirled closer, officials had enough information to ready resources and warn residents.

Global models that scientists rely on to issue forecasts are good at “sniffing out that there’s some potential of an impactful storm at least several days in advance” said Alex Lamers, the warning coordination meteorologist for the Weather Prediction Center, but specifics don’t take shape until the storm is quite close.

“The details really do matter—the exact location that it is intersecting the coast, which mountain ranges it is impacting, the angle the winds are impacting the mountains and the upslope regions,” Lamers said.

Satellites can only go so far in filling gaps in information over the ocean. “The Pacific Ocean is a vast expanse and there are not a lot of actual weather observations there,” he said.

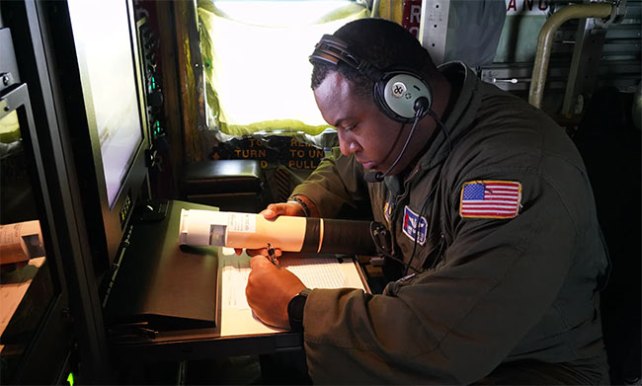

A weather reconnaissance squadron loadmaster checks a dropsonde during a California atmospheric river research mission.

Jessica Kendziorek/403rd wing public affairs

That’s why a team of scientists led by Martin Ralph, the founding director of the center for western weather and water extremes at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, began taking measurements directly from inside the storm systems themselves.

Since 2016, the atmospheric river reconnaissance program (AR recon) has relied on US air force “hurricane hunter” planes that drop a small cluster of instruments, known as dropsondes, that can transmit findings as they fall through the clouds and into the ocean below.

Fixed to a small parachute, each dropsonde floats through the clouds and into the ocean—a trip that takes roughly 20 minutes—all the while feeding important observations back to scientists on board. Air temperature, pressure, water vapor and wind speed are all collected by the dropsondes, like an “MRI for an atmospheric river,” according to Ralph, enabling researchers to see inside the system rather than having to rely on satellite imagery.

During a series of strong atmospheric river storms that hit California in 2023, the dropsondes helped advance some forecasts of heavy precipitation by roughly 12 percent, an achievement researchers believe would have taken eight additional years using traditional data-gathering methods.

Scientists with Scripps Institution of Oceanography fill a weather balloon before a test launch.

Yuba Water Agency

“If we get the atmospheric river wrong in the model—how strong it is, where it is situated, its structure, how much water it has—those errors are going to create errors in the forecast over time into the future,” Ralph said, explaining the importance of going to the specific location of an atmospheric river to measure it.

Along with the parachuting dropsondes, traditional weather balloons released from the ground during the storms, called radiosondes, help complete the picture. “They are very different approaches but both are needed to have the most effective prediction system,” Ralph said.

The team is also utilizing new technology, including a method called airborne radio occultation, invented by a Scripps geophysicist and atmospheric scientist, Jennifer Haase. While dropsondes take measurements as they fall vertically underneath the plane, ARO uses sensors attached to the side of an airplane that take measurements horizontally. They can infer properties like moisture and temperature by measuring how much GPS signals refract as they move through the atmosphere, helping scientists paint a more complete picture of an incoming storm.

The first flights equipped with ARO were deployed this winter and were able to collect data at a distance of up to 186 miles away from a plane.

Flood risks are growing in California and other parts of the arid American west, and having more precise intel will be essential to mitigating the worst disasters.

“Given the amount of warming we’ve seen so far, we expect that big precipitation events should be about 10 percent more intense than they were before greenhouse gasses were added to the atmosphere,” said Alex Hall, a UCLA atmospheric physicist and climate scientist.

“The scary thing is that if you look into the future to the point where we have twice as much warming as today, you have events that are 20 percent more intense, and entirely new classes of events that don’t even exist now.”

For Ralph, this reality is a call to arms.

“As those storms are going to evolve and change in time, our development of AR recon and associated tools to measure and predict atmospheric rivers will be able to keep up with that,” he said. “This really is a climate mitigation in order for humans to be better able to adapt to what’s happening.”