A recent rainy day in Oakland, California.Godofredo A. Vásquez/AP

This story was originally published by Wired and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Your city is a scab on the landscape: sidewalks, roads, parking lots, rooftops—the built environment repels water into sewers and then into the environment. Urban planners have been doing it for centuries, treating stormwater as a nuisance to be diverted away as quickly as possible to avoid flooding. Not only is that a waste of free water, it’s an increasingly precarious strategy, as climate change worsens droughts but also supercharges storms, dumping ever more rainfall on impervious cities.

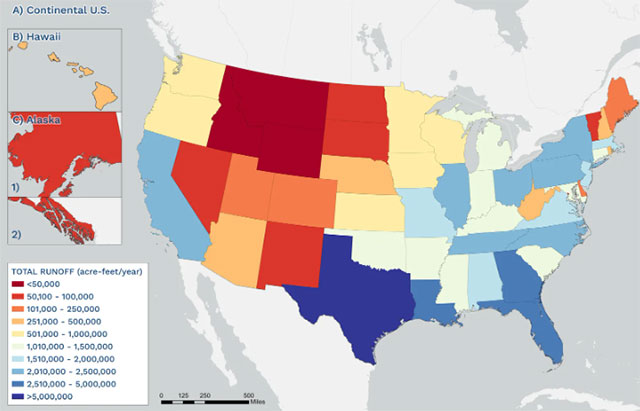

Urban areas in the United States generate an estimated 59.5 million acre-feet of stormwater runoff per year on average—equal to 53 billion gallons each day—according to a new report from the Pacific Institute, a nonprofit research group specializing in water. Over the course of the year, that equates to 93 percent of total municipal and industrial water use. American urban areas couldn’t feasibly capture all of that bountiful runoff, but a combination of smarter stormwater infrastructure and “sponge city” techniques like green spaces would make urban areas far more sustainable on a warming planet.

“There really is a substantial amount of stormwater runoff being generated all across the entire country,” says Bruk Berhanu, lead author of the report and a senior researcher at the Pacific Institute. “There really is no reason why stormwater capture shouldn’t be up there on the list of water sources for all communities in the country that are looking to secure their long-term supplies.”

The Pacific Institute did the calculation with the software company 2NDNATURE, which generated a high-resolution model of stormwater runoff for areas in the US with at least 2,000 housing units or 5,000 people. They combined characteristics of cities, such as the amount of impervious surface, with historical rainfall data.

In this map, blue signifies higher amounts of annual stormwater runoff from urban areas, while red is lower. States with relatively large amounts of precipitation and large urban areas, like Texas and Florida, are getting much more stormwater runoff than Montana and Idaho, where there’s less precipitation and less urban coverage. But even if it could, a given state wouldn’t want to capture every drop of stormwater falling on its cities, as rain also needs to replenish nearby rivers and lakes to sustain ecosystems.

This measure of 59.5 million acre-feet of annual stormwater runoff in the US comes from historical precipitation data. But going forward, climate change is messing with that rainfall in two main ways. It’s intensifying droughts, like in the American West, so there will be less rainfall in many places. And counterintuitively, because a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, rising temperatures result in heavier rainfall when it does rain.

“Even in areas that are becoming drier, we’re seeing more intense precipitation events,” says Heather Cooley, director of research at the Pacific Institute. “So the number this is generating is really an average annual number. And we think there is additional work to be done to look at the effects of climate change on runoff.”

The atmospheric river that soaked Los Angeles earlier this month, for example, was likely worsened by climate change. And LA, of all places, is actually paving the way for cities to better exploit the available stormwater highlighted in this new report. Or, technically speaking, the city is doing the opposite—the idea is to replace pavement with more dirt and greenery, which soaks up stormwater.

The spreading grounds in Los Angeles, where rainwater slowly seeps into the ground.

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power

LA was able to capture 8.6 billion gallons of water from that atmospheric river in just three days, in part by diverting it into huge “spreading grounds” to percolate into the dirt. “In most of the country, we’re going to expect—and we’re already seeing—larger, more intense storms that deliver a lot of water in a short amount of time, and then longer periods between the storm events,” says Seth Brown, executive director of the National Municipal Stormwater Alliance, which provided input for the new report. “There has been this growing trend of: let’s live with water, let’s embrace water where it is, let’s manage it and value it as a resource.”

The Cesar E. Chavez campus in Oakland, California, greened up by the Trust for Public Land.

Rebecca Friedlander/TPL

Even more locally, the nonprofit Trust for Public Land has been greening up alleys in LA with tree-planting projects. “We’re essentially tearing up alleys, putting in natural infrastructure and pervious surfaces,” says Guillermo Rodriguez, California state director at TPL, which wasn’t involved in the new report. The group is doing the same with schools, replacing asphalt with green spaces that counteract the urban heat island effect, in which the built environment absorbs the sun’s energy to raise temperatures. That’s especially critical in lower-income neighborhoods that get significantly hotter than richer neighborhoods, which tend to be greener. “We bring natural infrastructure in there and create shading, create stormwater capture, do all the important amenity benefits that deliver a cooler place to play,” says Rodriguez.

Another of the Trust for Public Land’s greened-up schoolyards—in Brooklyn, New York.

Alexa Hoyer/TPL

Even in the Eastern US, which is more water-blessed than the West, cities like New York and Pittsburgh are scrambling to deploy green infrastructure to mitigate flooding. That could be a simple roadside area, like a rain garden or bioswale. More cities are also adopting stormwater fees, charging landowners based on the amount of impervious surfaces on a property, thus encouraging them to open up more ground. Where an impervious surface is required, like a sidewalk or parking lot, cities are using “permeable pavers” with gaps that allow water to get through. Recharging aquifers this way helps prevent the over-extraction of groundwater, which is causing the land itself to sink, known as subsidence.

No longer a liability to be disposed of as quickly as possible, stormwater is becoming a bigger and bigger asset across the US. “We’re going the right direction. It’s just going to take decades for this to happen,” says Brown. “I think we’re just going to accelerate that as we see the forces of climate change.”