Lemon_tm/iStock

In a mesmerizing recent article, Mother Jones’ Tim Murphy recounts the surprising backstory of one of corporate marketing’s greatest flops: Coca-Cola’s quickly aborted 1985 effort to tweak its formula and convince consumers to accept “New Coke.”

Tim Murphy is on this week’s episode of Bite, talking about New Coke and doing a blind taste-test:

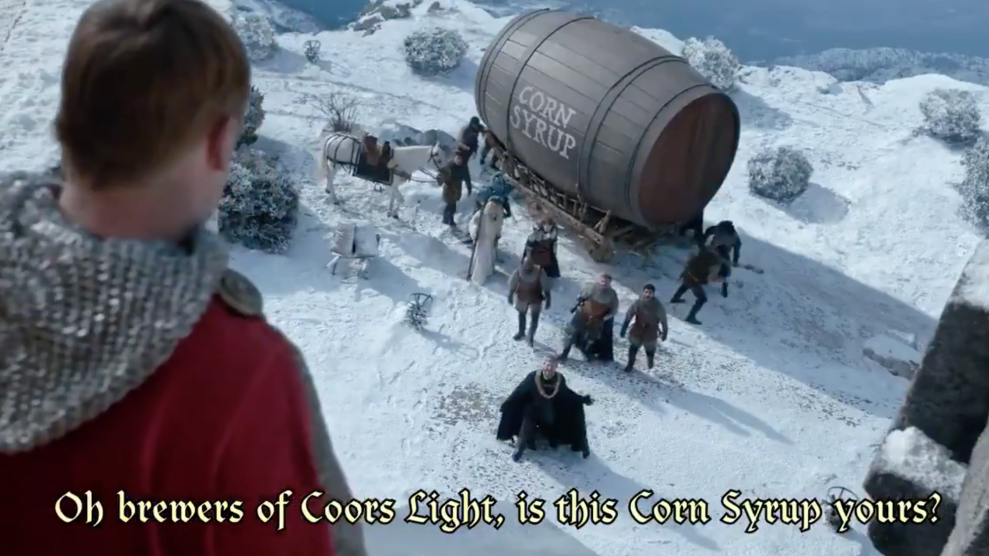

The piece ends with a twist I didn’t see coming (spoiler alert). Gay Mullins, the eccentric Oregonian who launched a crusade to restore the old formula, wasn’t satisfied when the beverage giant caved in to his demand. Soon after the restoration of Coke Classic, Mullins held a press conference to complain that it tasted differently from the Coke he remembered, because it was made with corn syrup. He declared he “would not rest until Coke was once more made with real sugar,” Murphy reports.

Mullins’ “pivot to high-fructose agitation” turned out to be as much of a bust as the New Coke he helped kill. Coca-Cola had already started adding high-fructose corn syrup to the mix five years before the New Coke fiasco. By 1984, a year before New Coke’s debut, the switch was complete: sugar out, HFCS in. “Mullins hoped that by joining the pile-on, he might entice the trade association to cut him in on some profits,” Murphy writes. “We were interested in being supported by the Sugar Association,” Mullins admitted.

How did high-fructose corn syrup take over for sugar as the soda industry’s sweetener of choice, anyway?

The conventional story, laid out by Huffington Post’s Julia Thompson in 2013, goes like this: “Nearly 30 years ago, Coca-Cola switched over from sugar to high-fructose corn syrup to sweeten America’s beloved carbonated soft drink. With corn subsidized by the government, its sugary syrup became a more affordable option for the beverage company.” So: corn subsidies begat cheap corn, which in turn lead to a corn-derived sweetener cheaper than sugar. Voila: HFCS takes over the soda market.

But while corn subsidies played a role in the story, another, less-famous government intervention likely played an even bigger role. The tale—which I first saw laid out in Richard Manning’s excellent 2005 book Against the Grain—started in the early 1971, when a massive, surprise sale of US grain to the Soviet Union triggered a boom in corn prices, which in turn led to a massive ramp-up in corn planting. By the mid-’70s, corn prices had returned to earth; but buoyed by subsidies, farmers kept planting “fencerow to fencerow,” as then-department of agriculture chief Earl Butz put it. The result: massive overproduction of corn. (The current corn glut, on the heels of the ethanol-driven boom of 2006-2012, followed a similar pattern.)

Corn-processing giants like Archer Daniels Midland had access to all the cheap corn they could ever want, but could only make a profit with it if they could find new markets for corn products. The company came up with two big ideas: ethanol, designed to disrupt the massive gasoline market; and high-fructose corn syrup, which the company hoped would break up Big Sugar’s hold on the soda industry.

They’re related, because both involve a process called “wet-milling” that isolates corn’s starch. To make ethanol, you ferment the starch and distill it into pure alcohol. To make HFCS, you add an enzyme to the starch that transforms some of its glucose into fructose—producing something with a sweetness profile similar to sugar. A single wet-milling plant could make both, and ADM began investing big in wet-milling in the early 1970s, a time when high gasoline and sugar prices offered opportunity for cheaper substitutes.

The company was led by an industry titan named Dwayne Andreas (vintage 1995 Mother Jones profile of him here). Hailed by PBS’s Frontline as “perhaps America’s champion all-time campaign contributor,” Andreas gained legendary status as a political double-dealer during the Watergate investigations, when congressional hearings revealed that he was the source of the $25,000 used by Richard Nixon’s “plumbers” to finance the 1972 famous hotel break-in. From the same investigation, it emerged that in 1968, Andreas had illegally donated $100,000 to Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humphrey—Nixon’s Democratic opponent in that year’s election, and a longtime Andreas favorite.

Despite political machinations that led to large production subsidies, the ethanol boom Andreas hoped for didn’t materialize until the mid-aughts, mainly because gasoline prices plunged after reaching dizzying heights in the mid-’70s. High-fructose corn syrup got off to a rough start, too. In a seminal 1995 paper on ADM’s vaunted ability to get what it needed from Andreas’ friends in government, James Bovard of the libertarian Cato Institute reports:

ADM got into corn fructose production very heavily around 1974, just as sugar prices peaked on world markets. After ADM invested heavily to increase its capacity to produce high-fructose corn syrup ninefold, sugar prices plummeted from 65 cents to 8 cents per pound.

The reason: inexpensive foreign imports had driven down the sugar price. As a result, ADM could not make high-fructose corn syrup cheaply enough to compete. To overcome this obstacle, ADM succeeded not in the lab but rather in the political arena. Like a Midwestern Machiavelli, Andreas came up with an ingenious plan: support lobbying efforts by Florida sugarcane growers to convince Congress to impose a quota on foreign-produced sugar.

In 1981, Andreas got his wish. Newly elected President Ronald Reagan—another close ally of the ADM chief—signed a law placing high quotas on imported sugar, which quickly raised the domestic price of sugar to twice the price on global markets. Suddenly, HFCS was the cheaper sweetener, and the quota ensured that the domestic sugar price would remain elevated. Both Coke and Pepsi quickly started using more HFCS, Bovard reports.

In 1984—the year before New Coke’s launch—both companies publicly announced they had had made the switch. A Wall Street exec hailed the development as ”exciting news for the corn millers,” the New York Times reported. He added: ”They’ve committed large sums over the last decade to improving their products to gain these approvals, and now they’re going to get the payoffs. The industry’s outlook is good for next year and spectacular for 1986.”

Use of the corn sweetener took off. Note the big jump in the first half of the ’80s:

A decade later, HFCS was still riding high and Archer Daniels Midland remained the “driving force behind the sugar lobby in this year’s battle over the future of the sugar program,” Bovard reports, adding that the company “heavily bankrolled” Big Sugar’s ad campaign defending the quotas that year.

Andreas retired in 1999 and died in 2016, inspiring awed obituaries. The sugar quotas he championed remain in place. These days, corn syrup’s star has dimmed. The processed food industry has largely turned away from HFCS, as it became associated with empty calories and weight gain (there’s little evidence it’s any worse than sugar on those fronts). Cola sales have been declining for years, but Coke and Pepsi still use HFCS in their flagship products.

Gay Mullins, the star of Murphy’s New Coke saga, brought a gigantic soft drink brand to its knees, but he was no match for Andreas, this “secretive, freewheeling Minnesota businessman,” in the words of a 1978 New York Times piece, “[who] trades soybeans, buys banks, and finances politicians—all with apparently equal zest.”