America’s corn belt—a broad swath of land stretching from Nebraska to Ohio—ranks as the globe’s most agriculturally productive region during the summer months. Its farms churn out the bulk of domestically grown corn and soybeans, most of which goes to feed the livestock that satisfies our meat habit, makes cheap fat and sweeteners for Big Food, and produces the ethanol that constitutes about 10 percent of our car fuel.

It’s also an ecological basket case. Fertilizer-laden farm runoff pollutes rivers, lakes, and wells. Ultimately, these chemicals flow to the Gulf of Mexico, where they feed an algae bloom bigger than Connecticut that every year morphs into an aquatic dead zone. Worse, under assault from increasingly fierce storms, the Corn Belt’s fields are hemorrhaging its most precious resource, topsoil. In a 2021 study, researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, estimated that more than a third of the region has completely surrendered its topsoil layer. Crop yields are already starting to suffer, the paper reports.

There’s a deceptively simple trick that could help counteract this ecological unraveling, one that could keep food growing and help suck up climate-warming carbon in the process: Incentivize farmers to plant a bunch of trees.

The idea of trees sprouting from the low-slung green monotony might sound unhinged. Think of the Midwestern landscape before US settlers subjected it to the plow, and you probably picture grasses and flowers billowing in the wind. That vision largely rings true, but isn’t complete. Amid the tall-grass prairies and wetlands, trees and shrubs flourished in much of the region, reports Cornelia Mutel in her book The Emerald Horizon: The History of Nature in Iowa. “Open oak woodlands and savannas climbed the hills and lined ridgetops,” especially in the region’s east, she writes, while “denser floodplain forests filled river bottoms everywhere.”

Native Americans wove agriculture into this landscape, which also teemed with wildlife. They grew corn, beans, and squash in ridged gardens near settlements, and actively managed nut-bearing trees (hickories, walnuts, and acorns), often by thinning out lower-yielding ones to favor the most bountiful.

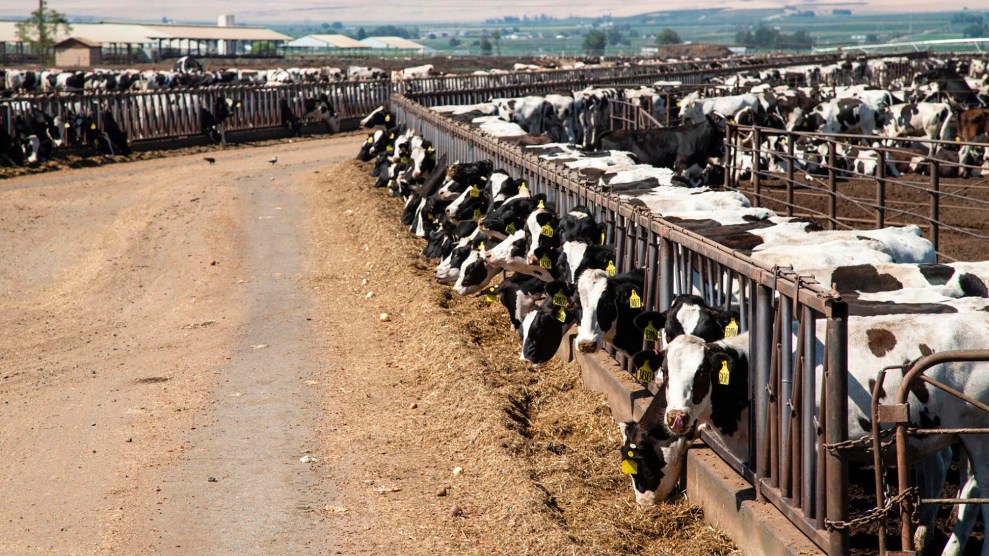

Everything changed soon after US enclosure in the mid-19th century, when settlers evicted most of the original inhabitants, drained wetlands, razed forests, and ripped into the land with plows. In place of staggering biodiversity, an agricultural empire featuring two main crops ultimately arose, tended with the tools of modern engineering and industry: genetically altered seeds, insect- and weed-killing chemicals, synthetic and mined fertilizers, and massive tractors and combines.

Reintroducing trees could bring big benefits to a reeling area—and to all of us who rely on it for sustenance, says Eric Toensmeier, senior fellow at the climate think tank Project Drawdown and a lecturer at Yale. Trees’ roots dig deep beneath the soil surface and fan out laterally, providing an anchor during heavy rain. They suck up nutrients all year long, keeping fertilizer from leaching away and polluting water. Trees shield crops and soil from the wind. And they both build carbon in the soil as their leaves drop and decompose, and also store it in their roots, trunks, and branches.

The intermixing of food-bearing trees and annual crops—an ancient practice known as agroforestry—could ultimately be more profitable for farmers than the current corn-soybean rotation in the Midwest, says Kevin Wolz, a farmer and the co–executive director of the Wisconsin-based Savanna Institute. “We certainly have more water here to grow trees compared to out West,” where a series of severe droughts has put pressure on California’s almond and pistachio groves, he says.

Wolz co-authored a peer-reviewed 2018 paper that found that growing black walnut groves in rows between fields of corn and soybeans—a practice known as alley cropping—would deliver more profits to landowners than field-crop-only farming on nearly a quarter of the region’s land. Other tree varieties, including hazelnuts, Chinese chestnuts, apples, and black currants, could work, too.

But breaking the all-corn-soybean habit will require a radical departure from today’s federal policy. Farmers currently growing those commodities get an immediate return from selling their crops at the end of the season. And even when prices are low, their profits are propped up by a bevy of government subsidies. So there’s little incentive to devote parts of their land to, say, walnut saplings, which would take years to pay off with a harvest.

A couple of existing federal initiatives can help finance a transition to alley cropping. The Conservation Reserve Program, for example, offers farmers annual payments to take land out of crop production, and can be used to compensate farmers to while they get agroforestry projects up and running. But so far, few farmers are taking advantage of it. “The reason is of course that the carrot is not attractive if there is no threat of a stick, and farmers are getting handsomely subsidized” for their current practices, says Silvia Secchi, associate professor of geographical and sustainability sciences at the University of Iowa.

One way to make trees enticing would be to force farmers to show they have plans to slash water pollution and soil erosion—say, a plan to add walnuts to their mix—before they can accept any subsidies. The agribusiness lobby would push back hard against such a policy—but it might just be what it takes to save a crucial food-growing region as we lurch into a future of accelerating climate chaos.