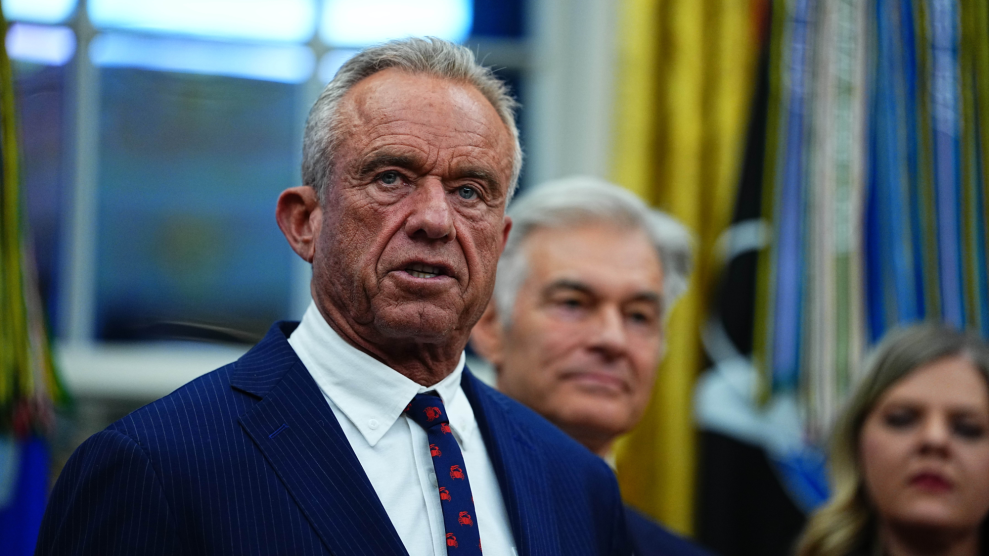

Photo: Andrea Nix Fine and Sean Fine

Sean Fine and Andrea Nix Fine have made documentary films in some of the wildest corners of the globe, from Inuit villages in the Arctic Circle and crocodile swamps in Botswana to a war zone in Colombia. But nothing prepared them for their shoot in a remote refugee camp in northern Uganda, where they’d planned to make a movie about former child soldiers. For the past 20 years, a messianic rebel group called the Lord’s Resistance Army has ravaged the region, abducting thousands of children and forcing them to commit atrocities in the name of its leader, would-be prophet Joseph Kony. Ninety percent of the local Acholi people now live in government-protected camps, but are still under constant threat of ambush by roving rebels. It is estimated that more than a third of Acholi boys and one-sixth of girls have been abducted for at least a day. “There’s no reasoning with the rebels,” says Sean. “I think it’s one of the most dangerous situations you could put yourself in, because they’re not in it for money; they’re just randomly terrorizing people.”

Yet the husband-and-wife filmmakers found that amid the chaos, the camp’s children were feverishly preparing for Uganda’s annual music competition, held in the capital, Kampala—a risky two-day trip away. The kids’ quest became the basis for the Fines’ film War/Dance, which won Sundance’s Documentary Directing Award and debuts in theatres in early November. Though they were clearly underdogs, the kids’ performance seemed to help them deal with their traumatic lives. “That’s what was so fascinating about the film,” says Sean. “It’s the power of music and art to heal people.”

Mother Jones: What were some of the risks you faced while making this film?

Sean Fine: The rebels were attacking pretty much everywhere. They would come at night and attack camps. They would ambush vehicles or people on the roads. You have to travel down the roads at maybe 80 to 100 miles per hour, and there are potholes three or four feet deep. You have to drive that fast because on either side of the road is 10- to 12-foot grass where rebels hang out. They were always there. We were always having people come up and say, “They were here last night. They stole a bunch of food.” We never saw a rebel. They wanted to meet with us at one point, but we decided not to. They wanted us to bring batteries and supplies, and it felt like a setup. A few days before we left, a truck full of kids was ambushed by rebels right outside of the camp. A truck like that? It’s a jackpot for them—it’s kids to abduct, big headlines for machine-gunning a truck. With the rebels, you’re dealing with a bunch of kids with guns who are terrified, who are doing something that a madman tells them to do. I think that’s why the danger aspect is so unpredictable.

MJ: How’d you find the children in the film?

SF: We heard about this music competition, and we thought, “This is a great idea.” Then we found out that this school, Patongo, was thinking of competing. It was a three-hour drive through rebel territory from where we were. I asked the translator what this place was like, and he said, “It’s the most dangerous, most vulnerable place. Even NGOs don’t go out there.” We decided that we really had to go out there because in this place, kids haven’t had a chance to tell their story. It was just magical—those kids got into our hearts right away. When you go to a place where no one’s helped people because it’s so dangerous, there’s a purity to it.

MJ: It’s hard to believe the kids in the film are only 13 and 14; they’re so articulate and open, even about the horrific trauma they’ve experienced.

Andrea Nix Fine: They’re old souls. I was so amazed by the kids. In a way, they’re very worldly. They’ve thought about how the rest of the world perceives them. I was really blown away by that.

SF: Because they were so cut off, they were anxious to get to Kampala to see what it was like. In the film, one girl, Nancy, says, “I want to know what peace looks like.” People ask me sometimes, “How could she say that, if she’s so cut off? How would she even know about peace?” They actually learn in school that there are peaceful places just a two-day trip from their home. But they can’t go there because of the rebels. When we went out to make this film, we thought that kids are always portrayed as victims in films about Africa or in war films a lot of times. But we wanted to make the film where what happened to them is not the sum of their life.

MJ: It seemed like they really trusted whoever was behind the camera.

SF: We don’t take the camera out right away. Also, with kids, we answer all their questions and let them know what this film is about and what it means to be in a movie. If one of them was going to meet us and they didn’t show up for four hours, or they go and do something else, we would just roll with it. You don’t get stressed out. One by one, we started to gain their trust.

MJ: When the children are talking about their past, it’s obvious that they’re profoundly sad. But when they’re preparing for the competition, they seem joyful. The contrast is jarring.

SF: That’s the reality. A good example is Rose. We noticed sometimes there’s this little girl off to the side, and she’s quiet, and sometimes she’s crying, and she’s by herself. And all of a sudden it’s her turn to dance, and she’s smiling and giggling. When she decided to talk to us, it was amazing to hear about how much music meant to her.

MJ: You chose to represent the flashback sequences with abstract montage sequences rather than traditional reenactments. How did you decide on this style?

SF: The style came a lot from our interviews. I think a kid remembers pretty difficult trauma in kind of weird snapshots. A lot of times during our interview, a kid would say, “I could smell the reeds around me,” or “It was so hot.” When we were filming Rose’s flashback sequence, there was a man that had a picture of what happened. It was the most gruesome picture I had ever seen: beheaded people lined all up and down the street, with a big cauldron with limbs sticking out. It was just awful. And he was trying to sell the picture to me. We could have bought that picture and showed people what it really looked like. But I don’t think you would have gotten the emotional impact that you got seeing Rose and hearing her talk about it and seeing her eyes, her face.

MJ: It must have been difficult to strike a balance between being journalistic observers and being so involved with these kids. You must have wanted to help them.

ANF: The proceeds from the ticket sales will go back to NGOs working on the ground. And there’s also a scholarship fund set up in Patongo. We’re distant from them in the sense that we go and make the film and leave, but we still know what’s going on with them. But the thing is, you get to say, “I get to go home” at the end of it. They don’t. At the end of the day, they’re the ones who have to continue to live there.

MJ: What are the kids up to now?

SF: Dominic’s in a secondary school, so he’s actually out of the camp. Academically, he’s doing really well. Nancy is also at a secondary school, doing extremely well. She’ll be a doctor hopefully; she wants to come back to the camp and open a clinic. The last day we filmed we finally met Rose’s uncle. We sat down, and he was like, “Rose is really special? She’s going to be in this film?” And we said, “Yeah, she’s really special! She’s amazing!” So he’s taken a liking to her now. She’s allowed to go to school; she’s smiling all the time. We’ve heard that ever since the competition she’s continued to be involved in music and dance.

ANF: Dominic has my cell phone number, because Sean left his cell phone there. So anytime I get this number on my cell phone that’s like 25 digits long, I know it’s Dominic. It doesn’t cost anything to receive a call, so he’ll dial and hang up. Usually it’s at three in the morning.

MJ: You usually work as a team. How did you share the responsibility of making War/Dance?

SF: For this film it was really different for us since we have a son, and he wasn’t even a year at the time that we made the film. So we decided to do something we’ve never done, which was to split up. But what actually ended up happening was pretty amazing. I’m the cinematographer, so I’m worrying about all the technical aspects. But I was also able to talk to Andrea, who was at home, removed from all the day-to-day stuff, so she could to take a big-picture look at what was going on and step back from it. It was really helpful.

MJ: How did you communicate during the filming?

SF: Where we were in Uganda, the only place to use my cell phone was on top of a small brick wall that was part of a brothel. I’d have to climb up and kind of balance between two bricks and hold the cell phone really high just to get a signal. Our calls would consist of 10-second conversations that would then get cut off.

MJ: What was the most difficult part of making the movie?

SF: I’ve been to a lot of war zones, and I’ve filmed in a lot of difficult places, and this was probably the hardest trip because I had a son this time. You’re seeing kids who are suffering all around you, and now you have a child yourself—it hits home that much harder. It was so sad because as a parent, your main objective is to protect your child. And when you can’t protect your child, that feels awful, and you feel so helpless. Now that I am a parent I was able to relate to that. In terms of filmmaking, there was a scene when Nancy was at her father’s grave and sobbing, and it went on for about an hour. I’ve never seen an emotion that raw in my entire life. I was wondering, “Do I really have the right to be here at the moment?”

ANF: But the more we talked about it and cut it together, we realized this had to be in the film. If you didn’t see this, you’d almost think, “Gosh, after 20 years do they just get used to the grief? Do they get used to losing their family?” And you realize, Yes, they’re coping, but they have this amazing sadness, and we wanted to make sure that it came across that they’re just like you.