Are civilian courts just a bunch of featherweights who can’t be trusted to try the al-Qaeda terrorist suspects imprisoned at Guantanamo? You’d think so if you listened to conservatives fulminating about it. But in Kill or Capture, Daniel Klaidman tells an interesting story. It takes place in the spring of 2009, while the debate over civilian trials was in high gear, and stars David Raskin, chief prosecutor of the New York Southern District Court’s terrorism unit, and one of his deputies, Adam Hickey:

It was while poring over thousands of secret documents pertaining to the Guantanamo detainees that Hickey made a stunning find: for years, it turned out, the military had been secretly recording the conversations of the 9/11 conspirators, including those of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. Every day, KSM was allowed to spend time in the prison yard mingling with other detainees. His conversations were intercepted by military spies and mined for intelligence.

….Raskin immediately understood the importance of the discovery. If KSM had talked openly about his role in 9/11, those statements would be among the most powerful evidence prosecutors could bring before a jury. They would be entirely voluntary statements, making them almost certainly admissible in court.

….The existence of secret recordings was surprising enough. But what Hickey told Raskin next was mind-boggling. Despite the potential gold mine the recording represented, military prosecutors had decided not to use the evidence. Not only that, they refused to even listen to the recordings. They worried that the intrusive means by which the evidence was obtained might not pass muster with their judges. The tribunals were  barely four years old and largely untested. With practically no case law built up to guide lawyers, they were reluctant to take any chances. In short, despite their reputation as less restricted, in this case military tribunals were more difficult venues for prosecutors.

barely four years old and largely untested. With practically no case law built up to guide lawyers, they were reluctant to take any chances. In short, despite their reputation as less restricted, in this case military tribunals were more difficult venues for prosecutors.

Fascinating, no? Perhaps we could have trusted civilian courts after all.

By the way, this is the second excerpt I’ve posted from Klaidman’s book, but I haven’t said much about the book itself. Generally speaking, it’s about the evolution of Barack Obama: how a guy who apparently was sincere about changing Bush-era policies regarding Guantanamo detainees and military tribunals ended up changing almost nothing. The book dives deeply into the conflicts between Obama’s advisors, most of them between the hawkish wing led by Rahm Emanuel (which Emanuel dubbed “Tammany Hall”) and the dovish wing led by Greg Craig and — usually — Eric Holder (“the Aspen Institute”). Obama was in the middle, and in Klaidman’s telling he was basically on the side of the Aspenites at first but eventually, and fitfully, ended up siding with the Tammany clique.

Why? Partly because the Aspenites didn’t understand the politics of national security very well and got outplayed. Partly because congressional opposition to transferring Guantanamo detainees to the mainland was simply too rabid. Partly because no one was ever able to offer Obama an alternative to Guantanamo and military tribunals that was both practically and politically feasible. Klaidman portrays Obama as uncomfortable with these decisions to this day, but no longer willing to reopen them. The politics are just too toxic.

On other subjects, Obama’s motivations were different. For example, he took a liking to drone attacks pretty quickly, seeing them as a much more precise method of killing al-Qaeda leaders than the alternatives. Drones, to Obama and his national security team, were attractive precisely because collateral damage from drone attacks tended to be far less than that from high-altitude bombing or military raids. As for the targeting of Anwar al-Awlaki, the American-born cleric who led the al-Qaeda franchise in Yemen, Klaidman reports that it wasn’t even a very close call. Because Awlaki was an American citizen, the decision to target him for assassination produced withering criticism in the liberal community (including some from me), but Klaidman says that the evidence of Awlaki’s terrorist activities was so voluminous and so chilling that Obama quickly agreed to put him on the kill list. Even Harold Koh, the liberal conscience of the State Department, was “shaken” after he spent hours in a secure room reviewing the evidence. “Awlaki wasn’t just evil,” Koh concluded, “he was satanic.”

And so the drone strikes continue and Guantanamo continues to be open and detainees are being tried in military tribunals. Obama isn’t willing to halt U.S. attacks on al-Qaeda completely — he takes the blowback argument seriously but doesn’t consider it decisive — and drones are the most effective way of carrying them out. He’d like to close Guantanamo, but Congress won’t allow detainees to be transferred to the U.S. and other countries don’t want them. And if you can’t bring detainees to the mainland, military tribunals are your only option.

I’m not vouching for Klaidman’s reporting here, and I’m not endorsing the Obama team’s judgments. But whether you approve of Obama’s approach or not, Kill or Capture does a pretty good job of explaining how the arguments unfolded and how the policies evolved. Recommended.

The EU bailout of Spain’s banks is a mere four days old and investors have now completed the raspberry they gave it on its first day. Yields on Spanish bonds shot up not just past 6 percent, which happened within hours of markets opening on Monday, but have now touched 7 percent, closing today at 6.92 percent. Clearly, the end is near. But that’s not all! Despite today’s news,

The EU bailout of Spain’s banks is a mere four days old and investors have now completed the raspberry they gave it on its first day. Yields on Spanish bonds shot up not just past 6 percent, which happened within hours of markets opening on Monday, but have now touched 7 percent, closing today at 6.92 percent. Clearly, the end is near. But that’s not all! Despite today’s news,

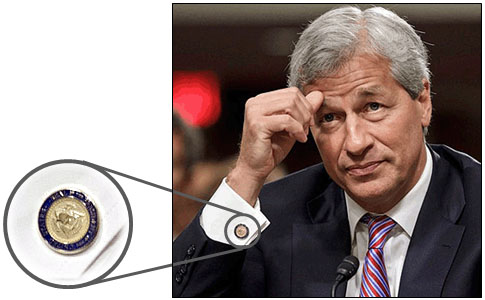

Republican senators in particular practically genuflected in his presence. No sir, nobody’s thinking about regulating you any more than you already are! Wouldn’t dream of it!

Republican senators in particular practically genuflected in his presence. No sir, nobody’s thinking about regulating you any more than you already are! Wouldn’t dream of it! never made it into the final piece. Jonathan Bernstein wonders if public complaints about this kind of behavior will

never made it into the final piece. Jonathan Bernstein wonders if public complaints about this kind of behavior will

barely four years old and largely untested. With practically no case law built up to guide lawyers, they were reluctant to take any chances. In short, despite their reputation as less restricted, in this case military tribunals were more difficult venues for prosecutors.

barely four years old and largely untested. With practically no case law built up to guide lawyers, they were reluctant to take any chances. In short, despite their reputation as less restricted, in this case military tribunals were more difficult venues for prosecutors.