California Gov. Jerry Brown, now and then<a href="http://ag.ca.gov/images/ag_brown.jpg">State of California</a>; <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:JerryBrownInauguration1975.jpg">Sacramento Bee</a>

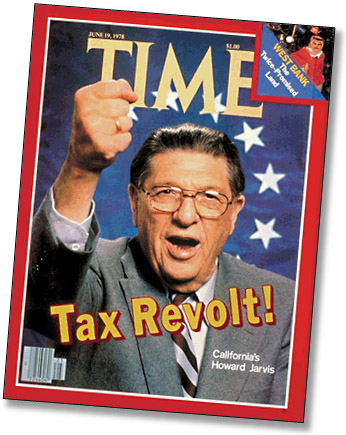

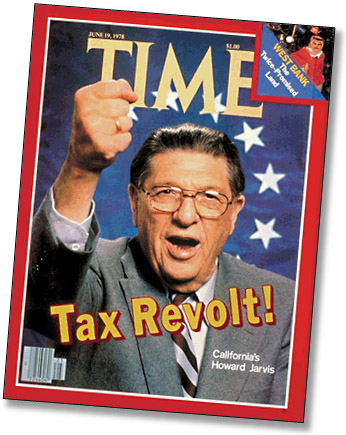

The great American tax revolt got its start in June 1978, when California voters passed Proposition 13, a ballot initiative that cut and capped property taxes and required a two-thirds vote to pass any future tax increases. Jerry Brown was governor back then, and initially he opposed Prop. 13. Once it passed, though, he became such a fervent apostle that four months later Howard Jarvis, the father of Prop. 13, was cutting campaign commercials for Brown’s reelection bid. Today, at age 74, Brown is no longer the Gov. Moonbeam that Garry Trudeau famously dubbed him back in the ’70s, but he is governor again. And guess what? In a Groundhog Day kind of way, Proposition 13 is back on the ballot again too.

Naturally, there’s a backstory here. The Golden State has had a rocky past decade, starting with over-optimistic spending during the dotcom boom; red ink as far as the eye could see during the dotcom bust; and finally, in 2003, a special election that propelled movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger into the governor’s mansion. Schwarzenegger won largely because of a second, mini-tax revolt, this time over an increase in the vehicle license fee, which he promised to roll back. He kept his promise, immediately plunging California back into deficit, and then passed a revenue bond that papered things over for a couple of years but, in the long run, just made California’s problems worse.

Still, for a couple of years toward the end of Schwarzenegger’s second term, the state budget started looking a little better. But it was just a mirage. California’s structural deficits had never really been addressed, and when the Great Recession hit in 2008 things went pear shaped fast. And while Republicans may be a fading force in California, they maintain just enough members in the Legislature to prevent any tax increases—thanks to Prop. 13’s two-thirds requirement—something which has left Sacramento with no choice but to slash the budget brutally. In current dollars, California spent $3,100 per resident out of its general fund in 2007. Today that’s down to $2,400. (Raw numbers here.)

Because of this, schools have suffered, universities have suffered, and, of course, the poor have suffered. Further cuts this year would cause even more devastation, so Brown is resorting, once again, to California’s initiative process to fix things. Ironically, though, this time he’s campaigning hard for Proposition 30, a measure that would temporarily increase  income taxes on the rich and sales taxes on everyone. The money would mostly be earmarked for K-12 schools and community colleges. If it doesn’t pass, automatic triggers in the 2013 budget will take effect, slashing $6 billion in planned spending.

income taxes on the rich and sales taxes on everyone. The money would mostly be earmarked for K-12 schools and community colleges. If it doesn’t pass, automatic triggers in the 2013 budget will take effect, slashing $6 billion in planned spending.

So here’s the question: Will California voters, who so famously started the tax revolt 34 years ago, agree to Brown’s plan to bypass the two-thirds requirement they themselves put in place and raise their own taxes? If Prop. 30 passes, it would symbolically mark an end to the tax revolt, and for this reason it’s attracted more than just the usual opposition from within California. It’s also attracted huge amounts of opposition funding from outside the state. Huge and mysterious: An Arizona outfit called Americans for Responsible Leadership has committed $11 million to the fight against Prop. 30 (as well as the fight for Prop. 32, a union-busting measure), but has steadfastly refused to disclose where the money came from. Under a court order, they finally revealed the source of the money on Monday, but they still had the last laugh: The source they revealed was just another mysterious organization, and it’s too late to force that organization to reveal the real source of the money. Andy Kroll has the whole story here.

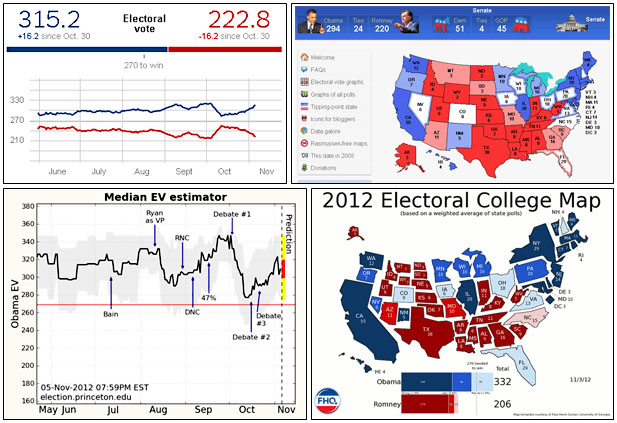

So will Prop. 30 pass? It’s on a knife edge. The most recent Field Poll, the gold standard in California polling, shows that all that outside money has had an effect. Support has dropped substantially over the past month, and now stands at 48 percent to 38 percent. A separate poll from PPP put Prop. 30’s support at 48 percent to 44 percent. That may seem like a comfortable lead, but conventional wisdom says that once an initiative drops below 50 percent, it’s in trouble. The undecided voters almost always end up voting No in large numbers.

So that’s where we stand. Today, at the behest of the same governor who came to personify the start of the tax revolt in America, Californians will decide whether they’ve had enough. After watching school funding and basic service funding atrophy for over a decade, is it finally time to call off the tax revolt? In a few hours, we’ll find out.

time encouraged people to view him in life-size terms, as a mortal figure who had done the best he could amid setbacks and disappointments.

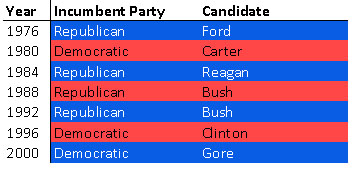

time encouraged people to view him in life-size terms, as a mortal figure who had done the best he could amid setbacks and disappointments. formula: the color of the incumbent party alternates every 4 years.

formula: the color of the incumbent party alternates every 4 years.

income taxes on the rich and sales taxes on everyone. The money would mostly be earmarked for K-12 schools and community colleges. If it doesn’t pass, automatic triggers in the 2013 budget will take effect, slashing $6 billion in planned spending.

income taxes on the rich and sales taxes on everyone. The money would mostly be earmarked for K-12 schools and community colleges. If it doesn’t pass, automatic triggers in the 2013 budget will take effect, slashing $6 billion in planned spending.

his childhood home, had received no notice that his own government prohibited him from flying.

his childhood home, had received no notice that his own government prohibited him from flying.