Thanks to the Obama administration’s sanctions regime, Iran’s currency is collapsing:

While the value of the rial has eroded for the past few years as Iran’s economic isolation has deepened, the severity of the drop worsened with surprising speed in recent days as Iranians rushed to sell rials for dollars. By the end of the day on Monday, it cost about 34,800 rials to buy $1 in Tehran. The rate had been 24,600 rials as of last Monday.

“It’s sort of in a full-blown stampede mode today,” said Cliff Kupchan, a Washington-based analyst at the Eurasia Group, a political risk consulting firm. “There’s very little confidence among many Iranians in the government’s ability to adroitly manage economic policy.”

Hey, it turns out that the sanctions against Iran really are crippling — so much so that even Mahmoud Admadinejad is admitting it and Benjamin Netanyahu now has sanctions fever. Based on my own sanctions model, I’d predict that the sanctions are now becoming so costly that Iran will in fact be willing to compromise on its nuclear program — but any concessions will seem tiny compared to how devastating the sanctions have been.

Regardless of what you think about Iran’s nuclear program (and the sanctions regime itself), there’s a lesson here: foreign policy isn’t always — or even often — about who can bluster the hardest. Nor is it about “red lines” and toughness. It’s messy. No one just sails from success to success. But Obama has pursued a sensible and persistent course against Iran’s nuclear program: first getting the world on his side by demonstrating a genuine willingness to engage with Iran’s leaders; pushing relentlessly for sanctions when that didn’t work; declining to back down when Iran tried to split the coalition he’d built; consistently turning down policy options that might have turned Iran’s people against him; and keeping military threats visible but always in the background.

Will it work? Anyone who claims to know for sure is a fool. It’s just too nonlinear. But if the Bolton/Cheney crowd could see beyond the ends of their own eyelashes, they’d realize that although Obama may be quieter than they are, he’s stuck to a pretty effective policy for years without blinking. And so far it looks like it’s working. For those of us who think that bombing foreign countries is a sign of failure, not a first best option, Obama deserves a pretty solid grade for how he’s handled things.

Michael Hiltzik writes today about who’s really the

Michael Hiltzik writes today about who’s really the

off the table. Today, Paul Ryan answered exactly that question after a woman at a town hall event told him she was

off the table. Today, Paul Ryan answered exactly that question after a woman at a town hall event told him she was  readers into thinking that multipage design is how the Web has always been, and how it should be.

readers into thinking that multipage design is how the Web has always been, and how it should be.

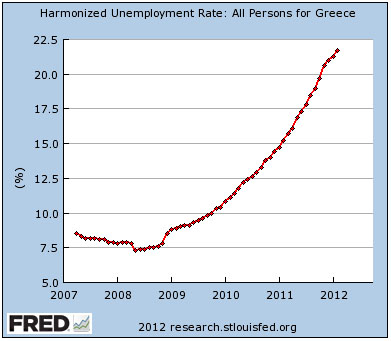

Fund — before it can be submitted for a parliamentary vote. The troika is insisting on further cuts in the public sector — including laying off public servants, a political third rail in Greece and other European countries — while the coalition government has been pushing back.

Fund — before it can be submitted for a parliamentary vote. The troika is insisting on further cuts in the public sector — including laying off public servants, a political third rail in Greece and other European countries — while the coalition government has been pushing back.