My neighboring city of Costa Mesa may be thousands of miles from New York and much, much smaller (population: 112,000), but they have something in common: police unions that don’t seem to know  when to quit. Check this out:

when to quit. Check this out:

An Orange County Superior Court judge on Wednesday ordered a private investigator to stay away from two Costa Mesa councilmen he allegedly helped surveil in the run-up to local 2012 elections.

….The false-imprisonment charge relates to the filing of a police report that caused Councilman Jim Righeimer to be detained briefly when an officer responded to his home to perform a sobriety test, according to prosecutors….[Scott Impola ‘s firm] was retained by the Costa Mesa Police Assn. to surveil and research local councilmen who were trying to cut pension costs and reduce jobs at City Hall, according to the Orange County district attorney’s office.

As part of their work, Impola and private investigator Chris Lanzillo allegedly put a GPS tracker on Councilman Steve Mensinger’s car and later called in a false DUI report on Righeimer as he was leaving Skosh Monahan’s, a restaurant owned by fellow Councilman Gary Monahan.

….Prosecutors say they have no evidence that the police union knew of any illegal activity beforehand.

Well, yeah. No evidence. But there is this:

Costa Mesa police officers mocked members of the City Council and suggested ways to catch them in compromising positions in the run-up to the 2012 municipal election, according to emails contained in court documents reviewed Monday by the Daily Pilot.

…. In one message, the association’s then-treasurer, Mitch Johnson, suggested telling the union’s lawyer about two of the councilmen’s upcoming city-sponsored trip to Las Vegas….”I’m sure they will be dealing with other ‘developer’ friends, maybe a Brown Act [violation] or two, and I think [Steve Mensinger is] a doper and has moral issues,” Johnson wrote in an email from a private account. “I could totally see him sniffing coke [off] a prostitute. Just a thought.“

Yes. “Just a thought.” I have a feeling that maybe the GPS and DUI revelations didn’t come as a big shock or anything when the union was confronted with them. There’s also this:

The association’s president at the time, Jason Chamness, told the grand jury that he asked the law firm to dig up dirt on certain City Council members because he believed they were corrupt. Shortly after the DUI report involving Righeimer, the union fired the law firm, although the affidavit notes the union continued to pay a retainer until as recently as January 2013.

During his testimony, Chamness also said he deleted emails from his private account, which he used to contact the law firm about union business.

And why did the police union hire these two goons? Because the city councilmen in question were trying to cut pension costs and reduce jobs at City Hall. How dare they?

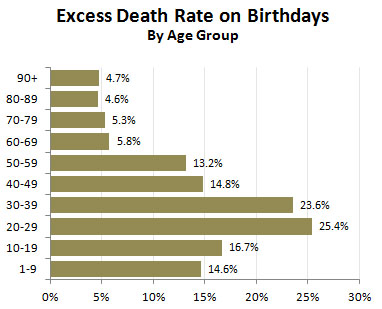

percent more likely to die on your birthday than on any other day. On weekends this rises to 48 percent.

percent more likely to die on your birthday than on any other day. On weekends this rises to 48 percent.

Medicaid recipients, 46 million food-stamp recipients — and many more.

Medicaid recipients, 46 million food-stamp recipients — and many more. but that is probably my own snobbery and cultural elitism coming in more than anything else. I don’t quite understand how explosion and bang wow movies are still big among a good chunk of the over-30 set.

but that is probably my own snobbery and cultural elitism coming in more than anything else. I don’t quite understand how explosion and bang wow movies are still big among a good chunk of the over-30 set. recommended Saturday by a panel they had created earlier this year.

recommended Saturday by a panel they had created earlier this year. when to quit.

when to quit.

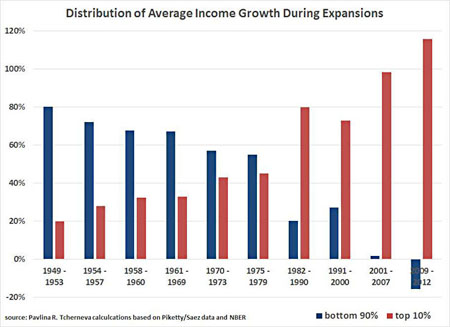

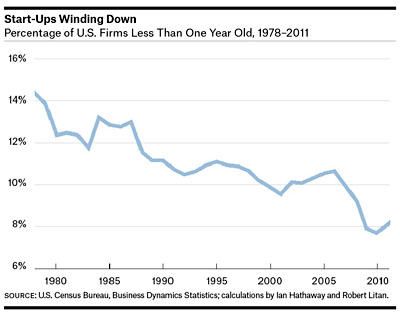

hardly big engines of economic growth—but I’m still willing to accept that some of it is probably real and deserves attention. The problem is what to do about it. James Pethokoukis, addressing skeptics like me,

hardly big engines of economic growth—but I’m still willing to accept that some of it is probably real and deserves attention. The problem is what to do about it. James Pethokoukis, addressing skeptics like me,  study 1, green-shirt or blue-shirt in study 2). And it turns that motivated reasoning happens way earlier and is

study 1, green-shirt or blue-shirt in study 2). And it turns that motivated reasoning happens way earlier and is