Nothing marked Bill Clinton as a new kind of Democrat more than his campaign

pledge to “end welfare as we know it.” Both blunt and

vague, the promise resonated with a view that the social safety net had become a web that ensnared

the underclass, particularly African Americans, in a gloomy pathology of dependency. Too many

of the poor, Clinton said, couldn’t even dream the American Dream.

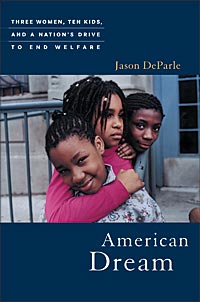

American Dream is the melancholy title Jason DeParle of the New York Times

chose for his richly researched, beautifully written chronicle of the era that fulfilled Clinton’s

pledge. Political abstractions are juxtaposed against the personal dramas of three emblematic

unwed mothers. By the book’s end, the women have 10 children between them, and one, at age 35,

is already a grandmother. At first glance, Angie, Jewell, and Opal seem to justify all the criticisms

of the welfare system: Each new birth ensures a larger welfare check; they move from Chicago to Milwaukee

for higher benefits and cheaper rent; they take jobs without telling the welfare office. Fathers

tend to be out of the picture—two are in prison for murder.

But DeParle’s intimate reporting reveals that welfare dependence

was a symptom, not a cause, of the chaotic happenstance of their lives. On a wrenching day when Angie,

in the stirrups preparing to end an unwanted pregnancy, abruptly halts the procedure, it is clear

that the prospect of a larger check is the last thing on her mind. These women are survi- vors, scuffling

by. When Washington moves to reform welfare, they shrug it off: They’ll manage. Two do so,

marginally improving their lots. The third, with no net to catch her, finds a bleaker fate.

Welfare reform is recalled as a triumph for Clinton, whose policy benefited

from a robust economy. DeParle’s judgment: The root cause of troubles in the African American

underclass was never welfare. But nobody has figured out how to legislate fatherhood.