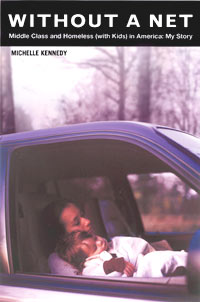

The summer she turned 25, Michelle Kennedy spent three months living in a decrepit Subaru station wagon with her three young children. They stayed in a small town on the coast of Maine, and she worked nights as a waitress. The family scraped along by eating ramen noodles, buying clothes at thrift stores, showering at a local truck stop, and sleeping in parking lots.

Many of the details about the family’s day-to-day survival are compelling, but it’s hard to muster much sympathy for Kennedy. After all, the book’s title, Without a Net, is not quite accurate. Kennedy actually does have a safety net: She has parents who care about her and who live 40 miles away. She could have picked up the phone, told them she was sleeping in her car, and asked for help, but instead–driven by a mixture of stubbornness and pride–she decided to persevere on her own.

Kennedy calls herself the “queen of bad judgment,” an assertion that’s hard to contest. She married her high school boyfriend, dropped out of American University, had three babies in quick succession, ran up her credit card debt, then followed her husband to Maine. The husband turned out to be a loser, and when she left him, her station wagon became her temporary home.

The title suggests a book packed with insights about what it means to be middle class and homeless, but Kennedy doesn’t deliver, in part because she writes narrowly about her own experiences. There’s no exploration of the myriad reasons—domestic abuse, drug addiction, a sick child and no health insurance—why educated young people can, and do, end up homeless. And while Kennedy touches briefly on the failure of the social safety net when she describes trying to qualify for Section 8—the federal program that provides housing vouchers to low-income people—she offers no context about the cuts to this program that have exacerbated the nation’s housing crisis.

Kennedy’s perseverance in saving money and finally finding a home for her family is impressive. In the end, though, Without a Net is less a meditation on homelessness than a first-person memoir about the steep cost of bad decisions.