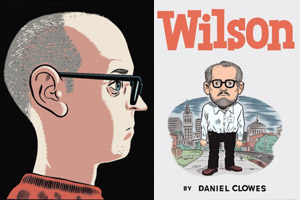

Adrian Tomine is not Ben Tanaka.

There. I’ve cleared up the confusion once and for all. Adrian Tomine is a cartoonist and illustrator, and Ben Tanaka is the protagonist of Tomine’s acclaimed comic book series, Optic Nerve. Now don’t get me wrong—the two have a few things in common: Tanaka and Tomine are in their 30s (Tanaka is 30, and Tomine is 33, to be precise), and they’re both Japanese American men. Tanaka and his friends live in Berkeley; Tomine lived in there for 15 years before moving to New York last year. But that’s pretty much where the similarities end. While Tanaka is cantankerous, Tomine comes off as upbeat and friendly. Tanaka suffers from major career inertia, but Tomine—with 11 issues of Optic Nerve, three other collections, a recently published graphic novel called Shortcomings, and a good number of New Yorker covers and illustrations under his belt—is ambitious and prolific, to say the least.

Yet some fans still have a hard time distinguishing fact from fiction. “There’s this whole notion of people wanting me to be a lifelong depressive loner or something,” says Tomine. The probable cause for their confusion: The world he’s created in Shortcomings (which is actually issues 8-11 of Optic Nerve) just seems so real. And in many cases, that’s because it is: The restaurants, bars, and cafés where the action takes place are mostly based on real places. And the characters—confused Ben Tanaka, his identity-politics-obsessed girlfriend Miko Hayashi, and his sassy best friend Alice Kim—seem like people you know, too. Tomine works hard to make it that way. “I think there are a lot of things that if my neighbors had any interest in peering into my studio window they would be shocked to see,” he says. “I’m just sitting here alone all day, but my lips are moving because I’m saying dialogue out loud, and I’m making poses and expressions in mirrors and stuff to get those things worked out.”

I talked to Tomine about the pros and cons of drawing super-realistic comics, his confused fans, and the real-life inspiration for a recent New Yorker cover.

Mother Jones: How are you liking New York?

Adrian Tomine: I like it. I was in the same area of Berkeley for about 15 years, so I was sort of happy to have some change in my life for sure. I feel like an outsider here, and I’m always pointing things out to native New Yorkers that I think are weird about this place and their culture and all that. But I feel like my friends and family from California feel like I’ve totally “become a New Yorker.”

MJ: I think there are some real cultural differences between New York and California.

AT: The West Coast seems so much more sensitive and politically correct. Not in a bad way, just attuned to that kind of thing. These words are so dangerous, but I see ignorance out here. I don’t mean that they’re morons, but they just don’t realize certain words are offensive to people.

MJ: Like what?

AT: In California, you would get into a lot of trouble if you referred to a person as Oriental.

MJ: Have you really heard that in New York?

AT: Oh yeah.

MJ: What about your work? Optic Nerve is pretty deeply rooted in Berkeley. Can we expect to see more New York? Or are you going to have to take research trips back to Berkeley?

AT: I’m not exactly sure. There’s a part of me that feels like it gets really frustrating to keep working in the manner that I made the book Shortcomings, where everything is pretty accurate to the real world. It gets kind of obsessive, and there’s a part of me that’s like, gosh, it must be really fun for these guys who just draw wizards and trolls running around forests, where it’s all made up and nothing matters.

MJ: The locations aren’t the only thing that seems super-realistic about Optic Nerve. The dialogue does, too. I wondered whether you take it from real life—whether it’s part of conversations you’ve had with your friends.

AT: In my earlier work, which was a lot more autobiographical, it was a lot easier for me to do that. I could just build a story around transcribing an actual dialogue or experience. With this book, which is a lot more fictional, I didn’t have that luxury, to sort of fall back on all real conversations and experiences. But I still have to be able to hear it or envision it in a real setting.

MJ: A lot of people have said that Optic Nerve is about racial and ethnic identity, but it seems to me that it’s more about identity politics, specifically the fact that identity politics are interesting and important to some people and totally annoying to others.

AT: I think you’re onto something there. There’s a lot of Asian stuff and the convergence between white and Asian cultures, but that specificity comes from my own experience, and I could have plugged different details into the story had I come from a different background, and I think it still would have worked. It has more to do with identity in general, and also not the specific ethnicities or the politics, but the ways in which people tend to confuse those with their more base desires or their own selfish needs, and how sometimes you can dress them up in fancier political terms to justify it.

MJ: It also seems to be about how people connect with each other and what sorts of issues people connect on. Ben Tanaka has a really tough time with that. He’s not the only comic book hero who’s that way—isolationist protagonists who have a hard time connecting are sort of a tradition. Why do you think that is?

AT: There’s a pretty common character trait, and it’s really well documented in the documentary Crumb, of using the act of drawing as a shield against the real world and a substitution for social interaction. I’m not quite as bitten by that bug as some of these other guys are because I am actually gripped even more by self-consciousness than by the need to draw or the fear of interacting with people. I look at some of these people’s sketchbooks like R. Crumb or Chris Ware, and these guys are in a different world from me. I draw kind of more as a means to an end, whereas R. Crumb has thousands of pages of place-mat drawings. He goes out to restaurants and draws on place mats, while I’m just focused on the food.

MJ: The comics world has definitely shifted toward graphic novels. Why do you think that is?

AT: A lot of it has to do with the physical mechanics of getting this material into people’s hands. There was a long time when comic book publishers, including my own, were trying to set up racks for comic books, but it just was not going to happen. I think that even if it’s taking a bunch of issues of a superhero comic and reprinting them with a spine, you’re going to sell a lot more copies. That sort of clicked in the minds of the public. The weird made-up marketing term of “graphic novel” suddenly seemed to make more sense, like, “Oh, they’re like books, but they’re in comic form.” As a result, that way of selling comics packaged as books has really taken off, and the old way, selling them as saddle-stitched magazines, has taken a hit. I can’t complain too much because I’ve definitely benefited from that change, so overall it was a positive thing, but I do feel bad for comic book shop owners, and it’s sad to see that old format pretty much disappear.

MJ: You started out just doing comics, but recently I’ve seen more and more of your stuff in The New Yorker. Was it hard to go from comics to illustrations?

AT: Initially I got into the whole world of illustration more out of financial need than anything else. I was always very torn when there was a lot of money being offered to promote something like a band or a movie that I didn’t care for. I felt like for most people, they don’t pay illustrations any mind, but if there’s just one fan of my comic who sees it and thinks, “Oh, well he must really like this band,” and then sees that it’s horrible, it’s sort of embarrassing. I’ve been able to cut out the horribly mercenary jobs and focus on things that are enjoyable to me. I’m an unabashed fan of The New Yorker. I do feel proud when I see my artwork in there.

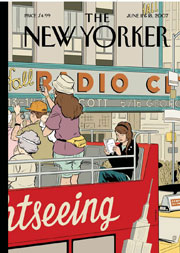

MJ: You did a cover for The New Yorker where a girl is reading what is obviously a J.D. Salinger book. Is Salinger an influence?

AT: There were a lot of personal elements that were tied into that image that don’t really mean anything for someone to enjoy it. At the time, my wife was working at Little, Brown and Company, who publishes those Salinger books, those white-covered books. Her office was right where you’d be standing if you saw that view that’s on the cover of that New Yorker. The girl in that image is modeled on my wife’s young sister. So there were a lot of things that were thrown into that one image that don’t mean anything to anyone else. So I think it wasn’t so much that I was saying, “I want the world to know I’m a big Salinger fan!” When you’re doing these covers you’re working in symbols and archetypes. I had to sort of quickly telegraph the idea that she might be a little hipper than her tourist parents.

MJ: I told some of my friends that I was going to interview you and asked them whether they had any questions for you. One said, “Yeah, will he marry me?” So do you find that there’s kind of a disconnect between your lonely and isolated characters and your status as an indie heartthrob?

AT: I didn’t know I had ever attained that status! The natural answer to all that is that I did get married a few months ago, and it’s been a source of curiosity for a lot of people. There’s also this whole notion of people wanting me to be a lifelong depressive loner or something. And I always feel like if that’s something that’s going to turn someone off to my work then my happiness is more important than theirs, to me at least. I went out on this promotional tour for the book right after I got married, and I tried not to talk about getting married that much, but somehow word got out and there were a lot of awkward interactions with readers at book signings. People would say, “Is your wife here?” She wasn’t with me; she didn’t go on the tour. So then they’d say, “Is she…white? Or Asian?” There’s this certain level of intimacy that some of my readers seem to feel comfortable with. I think there’s just something about the nature of the medium. It creates this illusion of intimacy just because it’s a work that’s created completely by one person, and it’s digested or read in isolation. It’s not like sitting in a movie theater with a hundred other people and all laughing at the same moments.