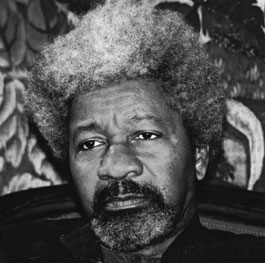

Sexism, sadly, is what comes through most strongly in Carlos Moore’s Fela: This Bitch of a Life, the newly rereleased 1982 authorized biography of Africa’s greatest musician, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Well, sexism and police brutality. The book, translated from the French, is essentially a well-organized and very long interview of Fela at his peak. For die-hard fans of the original Black President this may be a enticing read, but the average yuppie with an eclectic taste in music is probably better off checking out the Fela Project.

Fela is an natural topic for Moore, a scholar of race who’s led a very interesting life in his own right. Fela’s anticolonial message is a powerful one and there’s a lot to like about his politics and worldview (see video).

This is the Fela who was sold to me as a teenager into Bob Dylan, jam bands, and reggae. The Fela who created his own republic inside of Nigeria as an act of defiance, who relentlessly criticized the corrupt military regimes, who sang a song (“Zombie”) that actually triggered riots, who went to court more than 200 times and was unjustly in and out of prison his entire adult life. That’s all there, of course—and just how many times Fela and his crew were beaten, tortured, and imprisoned by the Nigerian authorities is a staggering reality that leaps out of Moore’s book.

But chances are you know about all that if you’re picking up Fela: This Bitch of a Life. What you probably didn’t know, but will learn in Chapter 20, is that “the law that says: ‘Don’t fuck until you’re sixteen,’ turns men into homosexuals and women into lesbians” or that “pollution, religion, and food… are the causes of homosexuality.” When it comes to women, the quotes are laughable: “Men and women are on two different levels,” and “Equality between male and female? No! Never! Impossible!” and, the topper, “Do I see man as being naturally superior to women? Naturally.”

A 65-page segment in the middle of the book consists of the same short interview conducted with each of the 15 wives, or queens, he had at the time (down from 27 at his mass marriage.) In nearly all the interviews the women admit that Fela had, on multiple occasions, slapped them, but that yes, they liked living with him.

A short paragraph describing the personal history and physical appearance of each wife reads like the plaque in front of an animal at a petting zoo (“Of average height and plumply slender, her broad, round face is studded with large, sensitive eyes and an expression of alert awareness.”) Moore isn’t doing much to empower the women or critique the hyperpatriarchy, and at one point asks a queen if she likes Fela’s penis. In this case, giving a voice to the voiceless doesn’t amount to anything and these pages are a bitch of a read.

How Fela became such a profound sexist is actually quite interesting because, unlike most people, he wasn’t born that way. Fela’s mother was a pioneering feminist activist, an incredible woman who in her capacity as president of the Women’s International Democratic Federation traveled the world, met with Mao personally, and was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1960. Fela’s own attitudes towards women emerged later, when, after living as an outsider in the racist London of the early 1960s and befriending Black Power advocates in the United States, he rediscovered his Africanness. Thus began a lifelong and entirely uncritical embrace of traditional African values, among them a very low opinion of women, formal education, and the threat of AIDS, of which he would die in 1997. A Mother Jones interview of Nobel Prize-winning Nigerian author Wole Soykinka mentions this specifically:

MJ: You write about your cousin, musician Fela Kuti, and how you think his own politics were kind of naive…

WS: Not think, were! He was a passionate Africanist. But his definition and embrace of Africanism did not discriminate: Anything that was African was positive. You would never hear a word against Idi Amin, against the monsters. He always accused me of being a CIA agent when I was campaigning against Idi Amin. He’d say, “Boss”—he called me “Boss”—“Boss Wole, don’t be influenced by the CIA people.” I said, “Shut up, you don’t know anything about it!”

To his credit, Moore has added a fabulous epilogue chronicling the decline and fall of Fela, contextualizing many of the performer’s views within a life that was puntuated by violence, incarceration, and illness. He also sets Fela alongside James Brown and Bob Marley as “the only 20th century musicians to have electrified the world with explicitly anti-establishment and unapologetically ghetto-inspired black music.”

Unlike Marley, Fela was an angry political organizer in open conflict with the state. You’ve got to give Fela props for not selling out. He could have acquiesced to the demands of western record companies, moved to Europe or the US, made millions selling a vague African revolution, and have his poster hanging in every college dorm room in the world, right between Che and Marley. Instead he decided to set up a massive commune in the middle of one of the poorest parts of Lagos, loudly and specifically criticize Nigeria’s military regimes, and give away all his money to friends, hangers on, and the poor. He died broke and crazy, of AIDS, and 1 million people filed by his glass casket, where he was laid to rest with a joint in his hand. “No one will force me out of this country,” he once said. “If it is not fit to live in, then our job is to make it fit.”

Ultimately, Fela’s story is a tragic one, a fact too easily forgotten while listening to his often mirthful, raucous albums. Reading Moore’s book restores an emotional weight to a music that was forged in protest, under duress, suffering from grief. The mournful ballad “Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake Am,” will leave your soul aching. This is Fela, he of the bitch of a life.