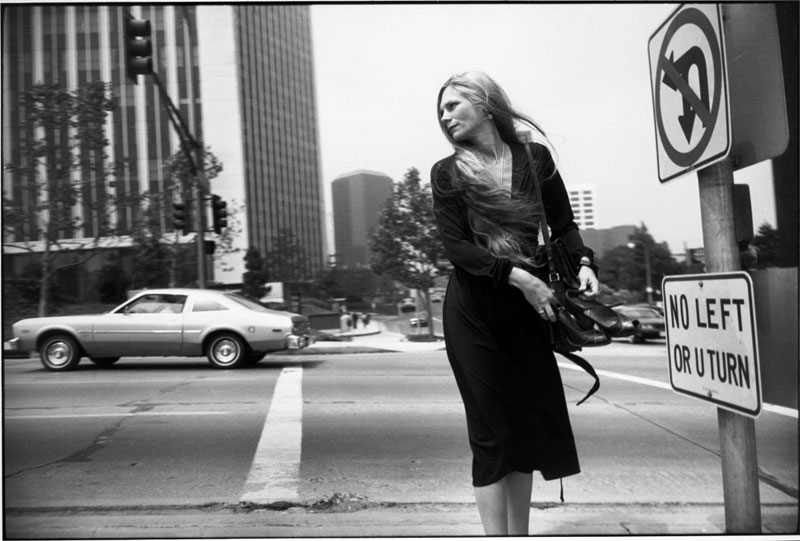

Garry Winogrand, on the prowl in Los Angeles.Ted Pushinsky

The GarryWinogrand retrospective is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York June 27 – September 21. From there it travels to the Jeu de Paume, Paris (October 14, 2014 through January 25, 2015); and the Fundacion MAPFRE, Madrid (March 3 through May 10, 2015).

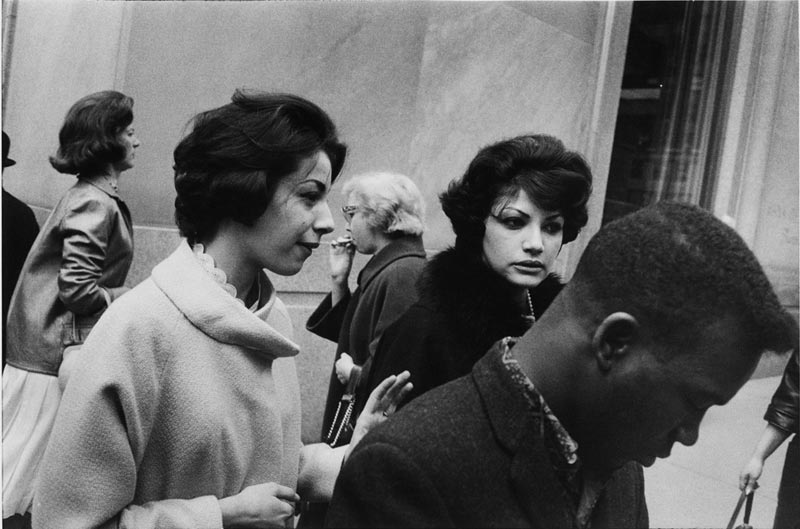

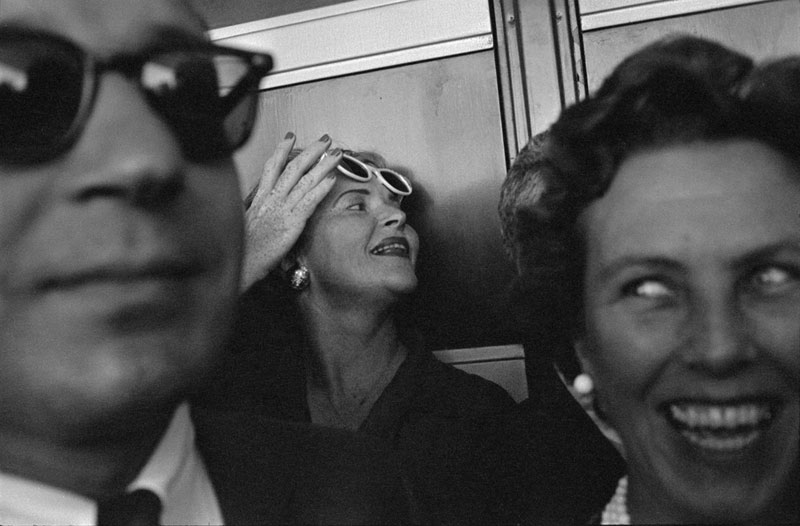

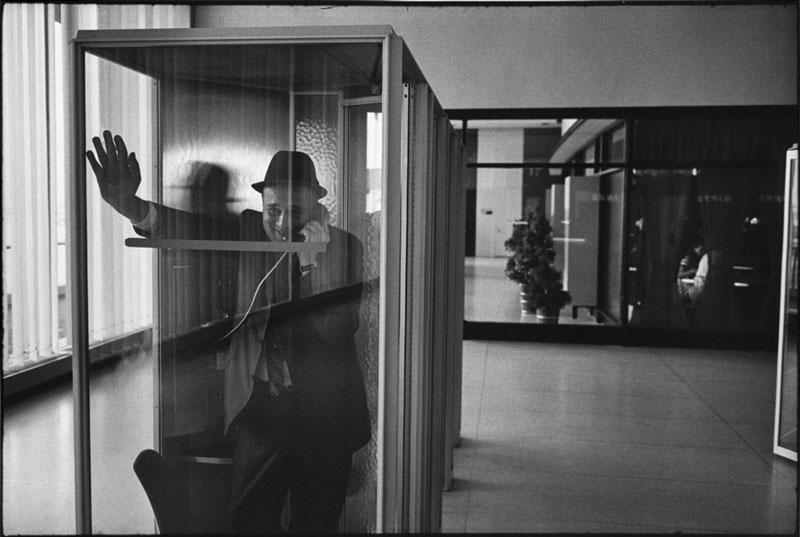

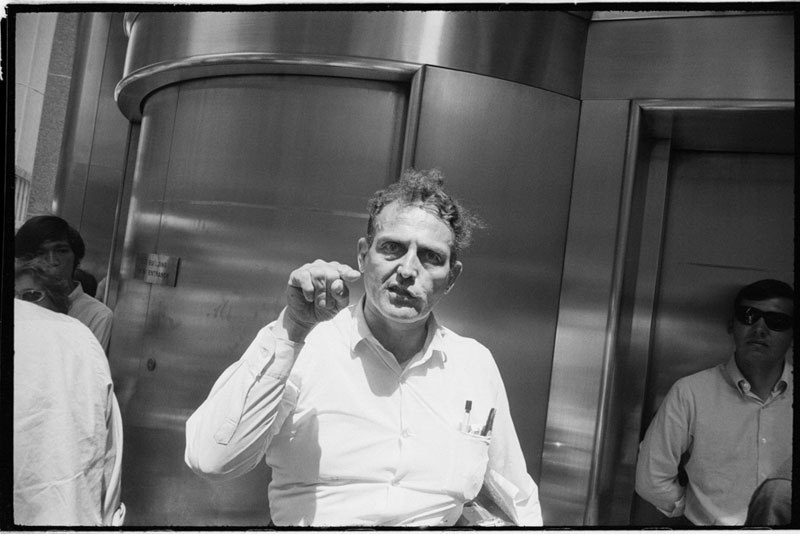

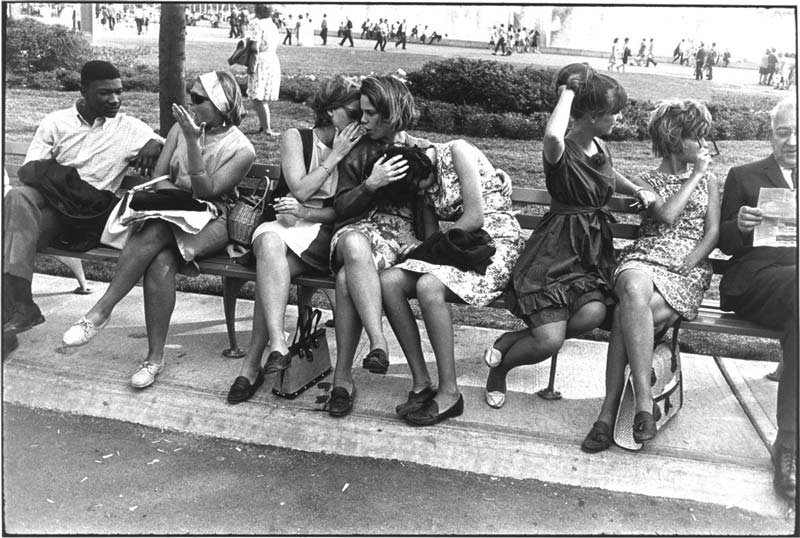

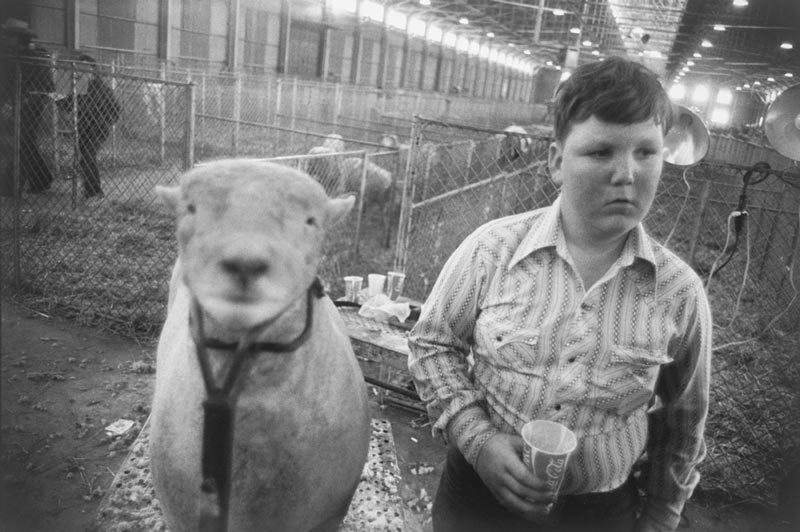

When Garry Winogrand died in 1984, the celebrated street photographer left behind close to 6,500 rolls of undeveloped film. Now his old friend and student Leo Rubinfien, along with Erin O’Toole, a curator at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, and Sarah Greenough, senior curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, have mined this trove to produce the first major Winogrand retrospective in almost three decades. The touring exhibit—which kicked off at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in March 2013—and accompanying catalog consist of more than 400 images derived largely from Winogrand’s later days roaming the streets of Los Angeles with his Leicas. While he may be best known for his New York City scenes, these photos prove that Winogrand’s wry eye could unpack the social complexities of Cold War America no matter where he prowled.

I went to check out the exhibit with San Francisco street photography legend Ted Pushinsky, who had casually mentioned he knew Winogrand toward the end of his life. (He shot the photo up above.) And as we took it all in, Pushinsky told me about their hangouts down in LA. It was a lot to take in. The massive exhibit borders on overwhelming, which is fitting given how prolific Winogrand was. It traces his career in something of a linear fashion, in three sections: Down From the Bronx (earlier work shot primarily while he was living in New York), A Student of America (his work from the mid-’60s through the ’70s, from all over America), and finally Boom and Bust (mostly shot in Southern California, and much of which has never been viewed). Hanging on the walls, intermingled with his photos, are Winogrand’s original contact sheets, pieces of this three Guggenheim Fellowship applications, letters to his daughters, and other personal artifacts. The phone book-size catalog gives photography fiends even more to chew on.

Ted Pushinsky: I met Garry at the San Francisco Art Institute around 1980. He was giving a lecture, speaking about his work, giving a slideshow. Definitely speaking off the cuff. I went up to introduce myself. I wasn’t necessarily an admirer of his work, but there was a photo in The Family of Man that meant a lot to me. I knew he took it. We had a mutual friend, so that was a basis for him saying, “Next time you’re in LA, come visit.” At the time I was writing screenplays, so I was back and forth in LA.

Mother Jones: You mention that you weren’t necessarily an admirer. So what prompted you to contact him in Los Angeles?

TP: Garry was a photographer of some stature whose work I got to know. Having the opportunity to spend some time with him, I was hoping some of what he knew would rub off on me. Going down to LA, I had the opportunity to walk the streets with him and see what drove him.

MJ: At this point in his life, in the early ’80s, just a few years before he died, Garry was well known for having people drive him around LA while he shot out the passenger window. I imagine you drove him a bit?

TP: I did the driving, yeah. I was staying in Santa Monica. I’d meet Garry at the Farmer’s Market, have some breakfast, get in my car and drive to Venice. We’d walk the streets of Venice, sometimes Hollywood. As Garry told me, “I don’t go on the freeways, I hang out the window and shoot.” I respected that. No big deal for me.

MJ: So do you feel like anything rubbed off on you?

TP: Perhaps a work ethic. Not anything in the way of teaching a way of seeing. I feel like I developed that myself. But Garry worked hard. He got up and started shooting. I get up and maybe read the newspaper. He shot an awful lot. It made me think, maybe I’m missing out if I’m not shooting.

MJ: Was there anything in the exhibit you recognized from when you were shooting with him?

TP: No, but what was great was seeing that picture from The Family of Man. It’s a couple in the surf at Coney Island. That was part of the basis of me wanting to meet Garry. Because my parents had met in Coney Island and there’s this photo of a couple shot from behind. I used to fantasize that it was my parents and it was shot by this guy named Garry Winogrand. And it turned out Garry went to the same high school as my father. Seeing that photograph was really great, in the Back to the Bronx section of the show.

MJ: You mentioned feeling a bit overwhelmed by the exhibit. I shared that feeling. Do you think there was too much?

TP: No. It was a great exhibit, like the [Diane] Arbus and [Robert] Frank exhibits. It requires two or three trips to the museum—to spend two or three hours in two rooms and come back to spend some more time.

MJ: Is Winogrand’s work worthy of a massive retrospective like this?

TP: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. He had a way of seeing unlike anybody else. The retrospective gives us the opportunity to see things that nobody had ever seen before. It was great.

MJ: And what about his later work? John Szarkowski, the former director of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art who put together the last large Winogrand exhibit in the late ’80s, was quite dismissive of it, and that’s partially what led Leo Rubinfien to revisit it in this exhibit. Does the later work hold up to his earlier work that he’s better known for?

TP: Absolutely. I was impressed by it. It was funny hearing Leo Rubinfien talking about Szarkowski not liking the work. I was surprised by that. I was was wondering what I would see. I though it was just as strong.

MJ: Do you think that’s because, as Leo mentioned, with the later work it might take going through 25 or 50 contact sheets to get one image that held up to the older work?

TP: Not at all. It wasn’t Garry that went through those 50 contact sheets. Garry might have found nothing worth printing at all. He might have found 30 worth putting up on the wall. It only had to do with Garry because he shot it. They did a great job though. Every picture was strong. There could have been more.

MJ: I’ve read criticism of people going back over his work, picking photos that he didn’t see. And they noted that in the exhibit—they mentioned which images Garry had marked on the contact sheets and which ones he hadn’t marked as selections to print.

TP: I saw that. I don’t think there’s a problem with that, unless he specified in his will as some artists do, “Throw away everything. Burn it all!” Then you hate the fact that maybe they burnt the Kafka manuscript that you didn’t get a chance to read. We were privileged to get to have someone do that for us.

MJ: When you would hang out with Garry, would you just drive him, or were you shooting alongside him?

TP: Oh, no. We would drive to a destination, usually the boardwalk in Venice or the Santa Monica pier. We would walk along together. I have some photographs of him shooting. I would try not to shoot what he’s shooting, but he’s shooting everything, so it’s hard not to.

Also not to be missed: The amazing photos of Vivian Maier, with an essay by author Alex Kotlowitz.