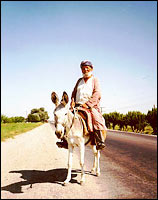

Image: Ted Rall

TASHKENT, Uzbekistan —Mikhail (not his real name) was dropping off a passenger from his deathtrap Lada taxi when the first bomb went off.

“I thought my life was ended,” Mikhail remembered. “Two buildings disintegrated a few hundred meters ahead of me. Things — pieces of the buildings, pieces of cars — were falling around me for at least a minute. Everything was on fire.”

Then the second bomb — actually a set of bombs — exploded in rapid-fire sequence. “One of the ministries fell into the street. I saw the militsia [the Uzbek military police] coming. I had a beard; not a long beard but still a beard, so I ran away.”

Mikhail wasn’t the only Uzbek who narrowly escaped the February 1999 bombing: so did President Islam Karimov, the hard-line, pro-Western, anti-fundamentalist leader of this former Soviet republic, who was a mere 200 meters away from the blast center when the government offices were destroyed. Those bombings in this capital city, largely considered to have been an attempt on Karimov’s life, were the start of the country’s counter-jihad that has cost hundreds of lives and led to countless border wars, and that threatens to topple a laughably fragile balance of power in this, perhaps the world’s most volatile region.

Uzbeks share a Central Asian brand of manifest destiny, believing that their country alone is equipped psychologically and militarily to act as Central Asia’s policemen. “Why do you want to go to Turkmenistan?” the Uzbek consul to New York asked me when I applied for my first visas to visit Central Asia, in 1997. “It’s nothing but desert. Kyrgyzstan is nice with the mountains, sure, but you see the mountains and then what? Kazakhstan is nothing more than an old nuclear-testing ground. Now Uzbekistan, we have 2,500 years of history, all the best cities, the best food. You should really just visit Uzbekistan.”

At first glance, Uzbekistan does have the most to offer the few Western tourists who make it past its arcane visa application forms, corrupt policemen and customs officials, and ocean of chickenshit bureaucracy (in town for more than a few hours? Don’t forget to register with OVIR — it used to be called the KGB.) The stunning Silk Road cities of Khiva, Bukhara, and Samarkand offer 13th century architecture to rival anything in Europe.

Tashkent, a bleak Soviet sprawl (everything and everyone was destroyed in a massive 1966 earthquake) that’s home to more than two million souls, is the primary transportation link to the outside world — the local cybercafé doesn’t actually have a computer, but you can get there by the world’s most architecturally majestic subway system. The land of 12-cent Cokes and 18-cent beers can be pretty pleasant, once you figure out the bizarro currency: The black market exchange rate between the US dollar and the Uzbek sum is three times higher than the official rate posted at banks, but banks actually exchange at the black market rate, which is perfectly legal but only temporarily.

As for the food, suffice it to say that a starving wild dog issued a yelp before racing away after I threw it my leftover shashlyk (mutton kabob).

But on this, my third trip to this gerrymandered-by-Stalin conglomeration of Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, and Kazakhs straddling the vast wastes of the Kyzylkym Desert to the west and the great Asian steppe to the east, it’s become painfully clear that Uzbek microimperialism has had dire consequences — mainly for the Uzbeks.

A year and a half after a still-anonymous would-be assassin attempted to kill Karimov, fighting raged 30 kilometers east of Tashkent between government troops and, well, nobody’s sure whom. The Termiz border crossing to Taliban-held sectors of Afghanistan has been shut since 1998 because local militants have taken to sniping at Uzbek troop transports.

|

The Uzbek-Tajik border, as my 23 fellow travelers and I were to discover a week later, was the scene of ferocious high-altitude fighting between the Kyrgyz Army and — well, nobody really knows whom for certain, but Karimov blames an outfit called the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which may or may not be the same group of guerillas numbering anywhere from 300 to 1,200 (nobody knows for sure) that held four Japanese oil company geologists and four mountain villages hostage for months late last year.

To add to the magnificent lack of reliable information, the IMU is said to comprise Tajik-based Uzbek Islamic fanatics, Taliban-trained Tajiks, or a secular coalition of Taliban, Tajiks, and Uzbeks. Their goal is to overthrow Karimov and establish Taliban-style rule in Uzbekistan and then in the other Stans, or to keep heroin supply lines open between Afghanistan and Turkey, or neither — again, depending on who’s doing the reporting.

Karimov clamped down on the Uzbek media, turning local newspapers into hilariously inane party organs (“Karimov announces all things better,” one daily blared upon my arrival at the brand-new Sheraton Tashkent.) More disturbingly, Karimov is so pissed off at nearly having been killed in the February 1999 bombings that he’s not letting his own lack of information stand in the way of state-ordered repression, especially targeting men who are or appear to be Muslim in order to stamp out what he suspects is radical Islamic violence.

As 1999 wore on, scores of suspects were rounded up and hung, some of them charged with no more than membership in militant Islamic organizations or mosques — often on evidence no more compelling than a long beard. Male residents of Tashkent have recently turned to a crisp, clean-cut look as a result. The executed have included men with disparate, and according to international observers, occasionally nonexistent ties to the Chechen resistance, Iranian-backed Hezbollah, and Central Asia’s favorite bogeymen, the Taliban.

During last year’s Kyrgyz hostage crisis, Karimov decided to take unilateral action against the Uzbek militants holed up along the A372 highway from Sary Tash to Dushanbe by asking the Kyrgyz to bomb the IMU-held villages. The Japanese government threatened to pull its fiscal aid if its four geologists stationed there were further endangered by bombing, so the Kyrgyz decided to try to starve the hostage-takers out. Ultimately, Karimov took bold and decisive action and called out an Uzbek air strike anyway against his neighbor’s territory.

Unfortunately, the Uzbek air force bombed the wrong villages, killing anywhere from a few dozen to hundreds of people — not even the Kyrgyz know for sure because the region is so remote, even by local standards. The Kyrgyz reacted by closing the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border and severing diplomatic ties. On their second sortie, the intrepid Uzbek pilots bombed the wrong towns again — this time on the Tajik side of the border. Fortunately for the Uzbeks, Tajikistan doesn’t have enough of an actual government to have a Tashkent embassy to close in the first place. In the end, the IMU fighters left of their own accord after the Kyrgyz promised them safe passage back to their bases in anarchic Tajikistan.

As might be expected from a man facing three simultaneous invasions by surrealistically anonymous ground forces, countless alleged assassination plots and his own narrow escape from Central Asia’s answer to the Oklahoma City bombing, Karimov sees himself as a man both personally and politically under siege. The Uzbek government sees an Afghanistan to the south full of training camps for young jihad fanatics who want to spread the Taliban’s brand of purist Islam (no music, no movies, no chicks). Tajikistan has no government worth mentioning, and its border with Uzbekistan is a constant battleground. Uzbekistan considers its other neighbors weak (Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan) or untrustworthy (Russia).

Needless to say (but let’s anyway), everyone else finds the Uzbeks presumptuous and annoying.

When there’s an unpleasant job to do, you’d best do it yourself, so Karimov says Uzbekistan will chase down and “crush and kill” radical Muslims wherever they go — without worrying about minor details like borders. In June, Russia’s Vladimir Putin accused Afghanistan of training and supplying the Chechen resistance; Uzbekistan not only offered safe passage to Russian bombers but asked for permission to send in its own ground troops. (The saber-rattling ended without comment in late July.)

It’s an old historical lesson, but the oppression of fringe movements often radicalizes people who would otherwise consider themselves moderate. A bus ride from Bukhara to Tashkent — normally a two-day ordeal of dusty, cramped seats, blaring Thai kickboxing movie soundtracks, and caged birds at the doors of death — can take four or five days thanks to an endless series of police checkpoints. AK47-toting kids in berets toss bags, demand bribes, and arrest anyone who kinda sorta looks Muslim — which is roughly a third of the populace.

Ugly allegations have surfaced about the fates of the arrested, thousands of whom have disappeared without a trace.

“Someday they’ll find the bodies,” an elderly woman moneychanger whispered to me in Samarkand’s bazaar at the foot of the majestic Registan mosque as a $50 bill bought sheaves of notes thicker than the Manhattan phone directories, white and yellow combined. “Everyone knows they kill them out in the desert.”

|

Checkpoints take anywhere from 15 minutes to three hours to clear, and they occur roughly every 30 miles. At first, my fellow travelers dealt with each new checkpoint with customary American good cheer, shouting out “Checkpoint!” to get everyone to sit down and assume the traditional Central Asian posture of glum fear the police expect from their subjects while they’re gleefully shaking them down. But suffering through that ritual dozens of times eventually made the glumness real. Uzbekistan has become a huge pain in the ass, even for the militantly anti-Muslim.

The vast majority of Uzbekistan’s Muslims want what people in Central Asia have always wanted: to be left the hell alone, to work and pray as they see fit. But faith has been politically polarized, and you’re either on one team or the other — and both sides have very, very big guns.