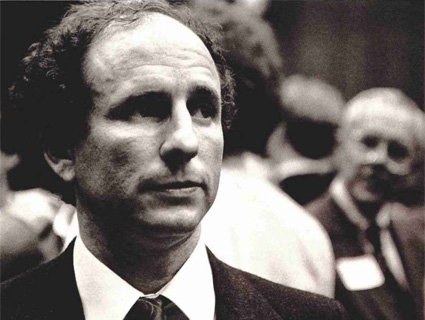

Photo: Terry Gydesen

It’s difficult now to recall the giddy sense of possibility that greeted Paul Wellstone’s 1990 election to the US Senate. Running against Minnesota Republican Rudy Boschwitz, a popular and seldom controversial incumbent with a $7 million war chest, he was widely considered the burnt offering of a state Democratic Party that had never really wanted him in the first place. Only weeks before Election Day, polls showed him running 16 points behind. Wellstone eventually triumphed by running a low-budget campaign that was risky, inventive, populist in tone, and unabashedly left-liberal. In so doing, he became the only candidate to unseat a Senate incumbent that year. If popular disgust for Beltway elites has become a matter of conventional wisdom in the decade since, it is easy to forget that Wellstone’s improbable win was among the first portents compelling the discomfited hordes of Washington pundits and party leaders to admit there was trouble in the air.

Wellstone quickly made a name for himself—first by openly denouncing the racist politics of Jesse Helms and his kind, and soon thereafter by emerging as one of the most vociferous critics of the war in the Persian Gulf. In the latter capacity, he made the rounds of TV talk shows and staged a controversial, emotionally charged press conference in front of the Vietnam War memorial. He was the “Senator from the Left,” exulted The Nation’s David Corn. Mother Jones held him up as “the first 1960s radical elected to the US Senate.” George Bush offered a more withering assessment: “Who is this chickenshit?” he muttered after being grilled by Wellstone at a reception for new members of Congress.

At the time, these seemed merely the first of what promised to be a long series of dust-ups between Wellstone and the Washington establishment. He was already on record committing himself to the pursuit of two measures absolutely anathema to the Beltway gang, namely the public financing of political campaigns and a government-financed single-payer health care system. To get anywhere at all with such an agenda, Wellstone realized, he would have to work with citizens’ groups and organizers across the country to rally public pressure. His chief role as senator, he said in those first months, was to begin working “with a lot of people around the country—progressive grassroots people, social-action activists—to extend the limits of what’s considered politically realistic. I have always been a community organizer, and I can do that here.”

Wellstone, in fact, was uniquely well qualified among members of Congress to take on such a task. During his years at Carleton College, the small, elite liberal arts school where he was a professor of political science, he organized and directed protest groups (supporting farmers who faced foreclosures and opposing South African investment, among other things); he also traveled the state building grassroots coalitions—most notably in the late 1970s, when he helped organize rural Minnesotans in a battle against a high-voltage power line.

Yet 10 years after he took his Senate seat, Wellstone has disappeared from the national consciousness. He never emerged as the left’s national spokesman for reforms in health care, campaign finance, or anything else. Apart from his abortive 1998 exploration of a 2000 presidential run—highlighted by a little-noted reenactment of Bobby Kennedy’s 1967 “poverty tour”—he has kept a generally low public profile.

When I spoke to him in the midst of his 1996 reelection campaign, we talked about what he deemed the greatest achievements of his first term. He first cited a largely symbolic ban on lobbyist gifts worth more than $100. He also told the story of uncovering and defeating an obscure provision that would have extended the patent on an arthritis drug called Lodine; had the measure passed, it would have meant another five years of inflated manufacturer profits. In each case, tellingly, Wellstone’s victories were mainly the product of masterful parliamentary maneuvers—laudable actions, no doubt, but hardly the stuff one expects of the “Senator from the Left.” He had fashioned himself into a formidable inside player; meanwhile, the grassroots organizing work he had once called his top priority never came to pass.

During his 1996 reelection campaign, I asked Wellstone why. He responded by describing the rigors of life in the Senate and concluding, “It’s taken a lot of time and energy to deal with that process, and I find it hard to do both. It’s very hard in terms of time.” In other words, his priorities had changed. It was not so much a disavowal of his political principles as a tactical decision about what it meant to be “senatorial.”

If it’s painfully clear that Wellstone sold out his best impulses along the way, the matter of how and why still bears examination. On that subject, Barry Casper—a longtime friend and fellow Carleton professor who accompanied Wellstone to DC in 1991 for a stint as a policy adviser—offers some firsthand insight. In his new book, Lost in Washington: Finding the Way Back to Democracy in America, Casper points to a few key moments in the fledgling senator’s seduction: the early embrace of then Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, who took Wellstone under his wing and saw to it that he received two plum committee assignments (Labor and Human Resources, Energy and Natural Resources), and the personal beseechings of Hillary Clinton, who cannily targeted the outspoken single-payer advocate as a potential adversary in promoting her managed care scheme. Hillary spent a good deal of time soliciting Wellstone and bending his ear; when the senator finally confided to Casper that he was thinking of supporting the Clinton plan, it became clear that her time had been well spent.

In a broader sense, though, it is the culture of Capitol Hill as a whole that conspires to change the Paul Wellstones of the world. To begin with, the sheer complexity of the social and procedural rules governing affairs on the Hill is an inducement to buy into the worldview: You can’t play the game if you don’t know the rules, and learning the game is in itself a job that commands one’s full attention and commitment. Once so committed, the newcomer is helpless to resist the DC establishment’s almost mystical powers, foremost among them the capacity to define what’s “politically realistic” and to suppress all else.

As Casper points out, the taming of members of Congress begins in their own offices. Wellstone’s initial staff was composed almost entirely of activists like Casper, but over time the balance shifted toward Hill professionals—just as DC veterans had assured Casper it would. The livelihoods of professional legislative staffers depend entirely on their bosses’ “viability” and reelection; there is little question about where they stand on playing it safe versus playing the pariah.

On the floor, the comity and respect of one’s colleagues are bought at a price that precludes hanging on to serious left-liberal aspirations. (Wellstone began to play the vote-trading game early on, most auspiciously when he voted against government aid for the postwar rebuilding of Iraq.) The result is a kind of betrayal that typically goes unremarked: American liberals harbor a traditional weakness for the rhetoric of “working within the system,” no matter how absurd. This tends to obscure the fact that, for a person of Wellstone’s professed goals, the decision to work within the system as presently constituted bears unflattering resemblance to a compulsive gambler’s decision to slink off to the casino for one more go at beating the house.

The inevitable question is, what else could he have done? Simple: He could have done what he set out to do, which was to concentrate on mobilizing and building ties between left-liberal citizens and activists across the country. Doing so would have antagonized most of Wellstone’s colleagues and committed him to using his position as a bully pulpit. And, given the negative reaction back home to his early prominence in opposing the Gulf War, it might well have meant he’d serve only one term. But there’s every reason to think it would have been a more honorable and productive course than the one Wellstone chose. If he had kept to plan, he might have forged something lasting, a legacy he and others could have continued building when his Washington days were through.

As it is, political observers now speculate that Wellstone may run for a third term in 2002, in express violation of a pledge he made in 1990 and again in 1996. If he does run, and if the Republican opposing him is even marginally more inspiring than the soporific Boschwitz, he may very well lose. And he’ll lose owing to the public perception that, contrary to his two-terms-and-out promise and all that it implied, he went to Washington and became just another career politician.