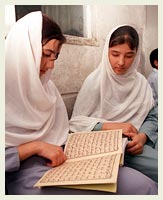

Image: Usman Kalizai

ISLAMABAD — For the students and teachers at the Malalay Afghan refugee school here, the US offensive in Afghanistan is simply one more link in a familiar chain of violence.

Some 700 boys and girls are enrolled in the school, all of them members of Afghan families that have sought safety in this sprawling Pakistani capital some 125 miles from the Afghan border. Some have been in Pakistan for a decade or more. Others arrived only recently.

But the students, aged 5 to 19, share a common experience: they all became intimately acquainted with the brutality of war long before the United States began its bombing campaign. Some have seen rockets flatten their homes. Some have seen loved ones killed.

Now, as refugees, they are no longer dodging bullets. But the violence in their homeland continues to color their daily lives.

At one of Malalay’s two locations, in the city’s predominantly Afghan Karachi Company neighborhood, a rust-colored cloth separates the street from an apartment whose five rooms have been converted into classrooms, each equipped with timeworn blackboards and about a dozen wooden chairs.

Neelab Hanifi, a 19 year old senior, comes to school despite the fact that she’s fighting malaria. Her family came to Pakistan from Kabul five years ago, fleeing the internal fighting that followed the collapse of Afghanistan’s communist government.

“When I think about the rockets falling now, I have flashbacks to when I was in Kabul hiding from them,” she says. “People are so worried. But we have no choice but to be here right now.”

Male students report being harassed by militant Pakistanis and Afghans, who pressure them to join the war against the United States. In the Peshawar More and Karachi Company neighborhoods, from which the school draws most of its students, children say they fear the return of Taliban recruiters, who three years ago scoured shops and streets in search of fighters. On a recent Friday many students and teachers stayed home, fearing violence associated with expected demonstrations by Taliban supporters.

The school itself has become a target for Taliban supporters because of the simple fact that it enrolls boys and girls together.

“They want us to shut it down or separate boys and girls,” says Malalay’s principal, Nooria Maroofi. “We have persevered to keep it the way it is so far.”

Maroofi says Taliban officials in Kabul sent her a letter in which they demanded that she “stop her activities” and threatened her life and her family. The letter, she says, was slipped under her office door. Taliban representatives in Islamabad declined to comment on the letter or the school.

Malalay was established in 1992 by Afghans whose refugee status meant their children were unable to enroll in Pakistani schools. Pakistan currently hosts some two million Afghan refugees. Malalay is one of some 50 schools that have sprung up to serve this swelling population.

The school employs 35 teachers, who make from $11 to $33 a month. About 30 percent of the students attend for free. The parents of the remaining students pay a nominal tuition fee, from $1 to $2.45 per month. Maroofi says the school has received individual donations of as much as $500, but has never received any support from relief organizations or the Pakistani government.

The result is a school that is unusually independent, answering only to the parents of the enrolled students. While giving them permission to operate, Pakistan does not recognize any of the Afghan refugee schools. A degree from one of the schools means little in Pakistan, so most of the students graduate with no opportunities for higher education.

“The only hope we have is that our children are being educated and the level of education is good, the same as it was in Kabul,” says Mohammed Arif Zarifi, a former engineer with three children enrolled at Malalay. “The problem is that they are (our) future, but in Pakistan, they have no future.” Zarifi says his eldest daughter hopes to go abroad to pursue her education, but the family cannot afford either the travel costs or the visa.

Maroofi says she is committed to keeping the school open despite the obstacles. But she echoed her students’ sentiment that the war has made life more difficult than it already was in Pakistan. Maroofi says the school’s neighbors are pressuring her to move because they fear an attack by pro-Taliban groups.

The Pakistani police offer little protection, students claim. Instead, they say police routinely press their parents for bribes over passport and visa issues — pressure they say has increased as the US campaign intensifies.

“In Pakistan, police harass us. We can’t leave our homes,” says Ajmal Wahadi, 15. “We’re afraid that they will take us to jail or send us to Afghanistan to fight.”

Ahmad Siar Mahboob, 11, recounts a typical tale. The boy says a Pakistani police officer stopped his father, an ice-cream vendor, demanding his passport. When Ahmad’s father showed the officer a 30-year-old passport, the boy says, the officer demanded a bribe. Ahmad says his father refused to give the officer money, and the officer responded by beating the middle-aged man with the butt of a rifle.

Having fled the regime, Maroofi says her students and their parents abhor the Taliban and what it has done to their country. But she draws no solace from the US campaign against the Taliban. For Malalay’s war-weary students and their families, she says, the only relief will come from a lasting peace.

“There are other alternatives that have not been explored. Let’s find those options and stop war,” Maroofi says. “Twenty-two years of war, for God’s sake, is enough.”