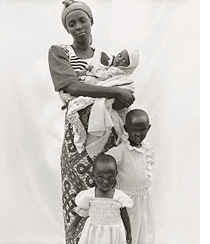

Image: Kimberlee Acquaro

On April 7, 1994, when the genocide was in its second day, Joseline Mujawamariya, then 17, huddled with her twin sister and younger brother in the tall grass on the outskirts of her village, Butamwe, in central Rwanda. They hid for three days as Hutu men and boys they had grown up with, armed with machetes, began a rampage of butchery and rape, burning homes and hunting down their Tutsi friends and neighbors. Then the Hutus set fire to the fields.

Joseline waited until nightfall, and as black smoke blotted the last light from the sky, she and the children fled. They joined a group of refugees that moved under the cover of night, living for more than two months on food scavenged from corpse-littered gardens and rainwater collected in cupped hands. Worse than the starvation and fatigue was the terror, Joseline says. “The Hutus would stop you to look at your fingers, your nose and ears to see if you were Tutsi.” In late June, the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front, invading from neighboring Uganda and Burundi, began to sweep through the country, driving out the Hutus. Ragged groups of refugees began to trek home, Joseline among them. When Joseline reached Butamwe, she found a ghost town. “There was no one left,” she says.

One morning last fall, Joseline stood on a hilltop overlooking Butamwe, her five-month-old son tied to her back. Before her stretched an undulating sea of banana groves and valleys creeping with hanging lakes of mist. Columns of smoke from cooking fires and controlled burns seemed to dangle groundward from the sky. A hundred Tutsi survivors were building a road over the mountainside to the capital, Kigali. Machetes arched through the high grass. Women with infants sleeping on their backs chopped through the rocky ground with hoes.

Joseline was their leader. Now 25 and a mother of three, with only a primary school education, she was elected in 1999 as the area’s head of development, after twice campaigning for other positions. “I didn’t know what I was supposed to do when I was first elected,” she said. “I thought I was supposed to buy a cow for the village.” What she now does is supervise the reconstruction of Butamwe’s shattered infrastructure, as well as its health services and systems of justice, education, culture, and economy. She is rebuilding her neighbors’ lives while struggling to rebuild her own. From the hill, Joseline pointed to the ruins of a mud structure crumbling in an overgrown field. “That was my home,” she said quietly, “where my parents and my brothers and sisters were all killed.”

The 1994 genocide, one of the worst mass slaughters in recorded history, was triggered by the assassination of Rwanda’s Hutu president, after a lengthy civil war between the Hutu-led government and the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front. It was a deliberate effort to eliminate the country’s Tutsi “problem”; books about Hitler and the Holocaust, and lists of potential victims, were later discovered in the offices of top government officials. In all, at least 1 million Tutsis and moderate Hutus died.

But it isn’t just numbers that set the genocide apart from other horrors of the late 20th century. The ferocity and concentration of the killing were unprecedented, as was its intimate methodology. The murderers were neighbors, relatives, teachers, doctors, even nuns and priests, and they killed not with machine guns or gas chambers, but with machetes, clubs, knives, and their bare hands. So many men were killed that Rwanda was left overwhelmingly female and became a nation of traumatized widows, orphans, and mothers of murdered children. Even today, the population remains 60 percent female.

Among the most nefarious tools of the genocide was a planned mass sexual assault on Tutsi women, with Hutu officials encouraging HIV-positive soldiers to take part in gang rapes. The United Nations has estimated that at least 250,000 women were raped, most of them repeatedly and over the course of weeks or months. (Some women we met remember being raped up to five times every day for 10 weeks.) Most of those women were killed afterward, but others were purposely kept alive to give birth to a population of fatherless “un-Tutsi.” According to one study by AVEGA, an association of genocide widows, 70 percent of women who survived the rapes — and many of their children — now have AIDS.

The genocide lasted three months, from April to June of 1994. It left Rwanda in physical ruins, completely destroying the country’s political, economic, and social structures. In a culture that historically prohibited its female population from performing the most rudimentary chores — from climbing on roofs to milking cows — women were now forced to take on tasks that had previously been out of reach. The result has been an unplanned — if not inadvertent — movement of female empowerment driven by national necessity. Traveling in Rwanda for three months last year, we found women heading households and businesses, serving as mayors and assuming cabinet positions. Rwanda’s Parliament is now 25 percent female, by far the highest proportion of women in national leadership in the world outside Scandinavia and nearly double the share of women in the U.S. Congress. “Men think this is a revolution,” says Angelique Kanyange, a student leader at Rwanda’s national university. “It’s not a revolution; it’s a development strategy.”

After the genocide ended, about 800,000 Tutsi refugees returned to Rwanda, swelling a rebounding flood of 2 million Hutus who had fled in fear of Tutsi retribution. Waiting for them was a population of “living dead,” dazed and grief-stricken survivors. In a country of only 7 million, national reconstruction required more than replacing murdered leaders and rebuilding razed homes. It was “a process of deconstruction as much as reconstruction — deconstructing ethnic perceptions, deconstructing gender stereotypes,” says Jack Hjelt, the former chief of the United States’ post-genocide humanitarian and development program in Rwanda. “From the destruction comes a unique opportunity to rebuild from the ground up.”

Before the genocide, women in positions of power had been rare, though not unheard of. (Rwanda’s prime minister at the time, a moderate Hutu who opposed the mass killing of Tutsis, was a woman; she was murdered and sexually mutilated in the first hours of the slaughter.) Now 18 percent of all top government jobs are held by women. Four women hold cabinet posts, including Angelina Muganza, who has been appointed to head the newly created Ministry for Women in Development.

“There is a history of division and misinformation particularly for illiterate, undereducated women in our country,” Muganza told us. Before the genocide, 55 percent of Rwanda’s women were illiterate (48 percent of the men couldn’t read), and many became easy prey to a relentless propaganda campaign dominated by newspaper cartoons portraying Tutsi women as salacious harlots set on seducing Hutu men and subverting Hutu families. With their wives’ misinformed consent, Hutu men were encouraged to rape and kill Tutsi women for the sake of Hutu “unity.”

Joseph Nzabirinda, a benevolent-looking 48-year-old former school bus driver, told us that he’d killed so many Tutsis he’d lost count. Joseph wore pink shorts and matching pink shirt, the universal prisoner’s uniform in Rwanda. He was awaiting sentencing by the local courts. Sitting straight-backed on his chair, his palms resting on his knees, he told us about his youngest victim, a one-year- old girl. “I had a boy the same age,” he said, struggling to compose himself. “I stood at the edge of a latrine and I remember dropping the baby down the hole and throwing stones on top of her. She was alive. When I threw her, I could hear she was still screaming.

“My wife knew I was killing Tutsis,” he said. “She told me, ‘If you don’t go, they’ll come here and kill me.’ She told me to go kill. Go so they don’t come.”

In some cases, women more directly participated in, even orchestrated, the slaughter. Last year, two Rwandan nuns, Gertrude Mukangango and Maria Kisito Mukabutera, were tried in Belgium and convicted of murder for their roles in the massacre of 7,000 Tutsis who had taken shelter in their convent. Rwanda’s minister for family and women’s affairs at the time the genocide began, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, is currently on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in Arusha, Tanzania. She is alleged to have personally directed squads of Hutu men to torture and butcher Tutsi men, and to rape and mutilate Tutsi women.

Today, Rwanda’s women and girls have one of the highest literacy rates in Africa — 61 percent. Boys and girls attend school at about the same rate, nearly 70 percent; before the genocide, boys outnumbered girls 9 to 1. Nearly half of university graduates are women, compared to 6 percent just 10 years ago. And for the first time, women have the right to own property; in the past, they could not keep their homes, or even their children, when their husbands or male relatives died.

Delphine Umutesi was 10 when she watched her father butchered by Hutus in her home. She was the eldest of five children, the youngest less than a year old. After the genocide, the children were housed in an orphanage. When it closed, Delphine, barely 14, found herself one of Rwanda’s 65,000 underage heads of household, a child taking care of other children. “I asked myself, ‘How will we live?'”

She moved her siblings back into their family’s mud home in rural Kigali. Technically she was a squatter there; then, in 1999, Parliament passed a law allowing women to inherit land, and she now owns the property. She has no time to go to school herself, but each morning she sends the others off to class and walks several miles to work. She feeds her family by making greeting cards from banana leaves — a micro-business that looks modest on the surface, but would have been impossible before the genocide, when women were not allowed to earn money independently. “I try to help them with their homework,” she says. “But soon they’ll know more than I learned in school.”

After Josephina Mukahkusi’s husband, five daughters, and two sons were slaughtered with machetes before her eyes, their Hutu killers beat her, then dumped her with her girls into a pit latrine, leaving her for dead. Eventually, she was rescued and lifted to the surface drenched in her daughters’ blood. Now 45, Josephina can’t recall if she lay there for hours or days. What she does remember is the desolation of being left alive, childless and alone. “The Hutu women looted after their husbands killed,” she told us. “Many of those women were my friends. We were godmothers to each other’s children.”

After the genocide, afraid to return home alone, Josephina moved into a shelter where she met and adopted a young Hutu orphan named Jane. Josephina and Jane have since returned to her village, where they live among people who took part in the killings. “We are raising their children,” she told us. “Jane’s mother was Hutu, but Jane is innocent.” Her hope, she said, is that Jane will grow up thinking of herself as Rwandan rather than Hutu or Tutsi.

Severa Mukakinani was forced to watch her seven children butchered, then was gang-raped repeatedly by their murderers. “The raping went on for a long time — I don’t know how long,” Severa, now 43, told us. “When they tired of me, they cut and beat me and threw me in the river.” She was left for dead, but survived to find that she was pregnant from the rapes. “I wanted to remove the baby. I decided to keep it, because I believe the child is innocent.” She named her daughter Akimana, which means “child of God.”

“Rwanda is like no other situation in the world,” says Barbara Ferris, founder and president of the International Women’s Democracy Center, which trains women to participate in politics in emerging democracies. Rwandan women have come this far, she says, in part by legally redefining women’s roles. “It’s logical that women move into formal leadership roles,” Ferris says. “Informally, women already are leaders. They want what every other woman wants for her children: a better life than they had, access to education, food on the table, and a roof over their head. If they have to enter politics to do it, that’s what they will do.”

At the State House in Kigali last June, Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame became animated when we asked him about the role of women. “Now we want to encourage women’s responsibility, not to just look to men,” he said. “We know in our conscience that there are women who can go to high levels of leadership, whereas before, women didn’t even know they should be playing leadership roles. So their consciousness is developing.”

He believes, he said, that women’s empowerment is a national imperative. Rwanda’s new constitution, now being drafted, will include passages that specifically address women’s rights.

Of Rwanda’s 106 mayors, five are now women. (There were none before the genocide.) One of them, Specioze Mukandutiye, spoke to us in her office in Save, in southern Rwanda. She bears a particular responsibility to rebuild the country, she said soberly, because she is a Hutu. Her Tutsi husband was murdered, though her four children survived. “Many times the Hutus tried to kill us,” she said, “because I was a moderate and any Hutu who didn’t follow them was killed.”

After the genocide, Specioze started a support group for genocide widows; she was the only Hutu member. She was appointed mayor by the government in 1995, then elected in 2001 by a mostly Tutsi constituency. In her years in office, Specioze told us, her ethnicity has been less of a barrier than her gender — though once exposed to women in leadership positions, she added, “the men began to understand that women are as able as men.”

Still, she noted with a mixture of sadness and irony, she would have gone nowhere politically had her husband survived. “I would have had to follow his instruction.” It’s difficult to balance her work and family, she told us, but she was determined to do it because “now is the moment for Rwandan women to demonstrate they can do the same jobs as men, and have the same value.”

Odette Mukakabera is one of the 200 women in Rwanda’s new 5,000-member national police force (the second-highest police official, the assistant commissioner, is also a woman). A teacher for 10 years before the civil war, Odette answered a recruitment call for female officers in 2000. Since joining the force, she has also gone public about the fact that she has AIDS, a rare step for women in Africa. Her husband died of AIDS shortly after the genocide, leaving her to raise four children alone while attending law school full time. “I am writing my dissertation on the rights of people living with HIV,” she told us in her office in police headquarters in Kigali. “I speak publicly about my condition to raise awareness. It is difficult to do all this-to be a mother and policewoman and student. But I am trying as long as I am still strong.”

Odette has not experienced discrimination within the force, she said, but out on the beat people often seem surprised to see a female officer. To most Rwandans, Deputy Police Commissioner Dennis Karera told us, women in uniform are still a novelty: “It’s a transformation process that everyone is going through.” But female officers are often more effective than men at solving crimes, he added. Rape and domestic violence are now reported more often than ever.

“At first, women asked us, ‘How will we do this?’ We answered, ‘You don’t need muscles to do investigations.'”

Whatever their position, says Minister for Women Muganza, women throughout Rwanda are learning to use their new authority to improve their, and their children’s, lives. “Rwanda’s women work together despite their differences,” she says. “Their attitude is, ‘What has happened has happened, but let’s make the future different.'”

Severa Mukakinani told us that she knows her daughter will have a better life, even though the present is a struggle. “I had seven children before, but I had a husband to feed them,” she said. “Now I only have one, but I can barely put breakfast on the table.” Many of the women we spoke to echoed the same sentiment. History, they said, has handed them both an extraordinary burden and an unprecedented opportunity. “Rwanda’s future,” Severa said, “is on our backs.”