When copies of Ambassador Karl Eikenberry’s classified cables showed up on the web site of the New York Times Monday night, the timing of the leak surely seemed suspicious. The controversial memos appeared just as two high-profile events were set to take place later in the week—one a conference in London to discuss Afghanistan’s future, and the second President Obama’s first State of the Union address where the US mission in Afghanistan is sure to figure in.

The memos, sent to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as the administration formulated its Afghanistan strategy, were first described by the Times in general terms last November. Back then, the disclosure of Eikenberry’s dissent was just the latest leak from administration factions that were apparently competing for influence in the Afghanistan debate. According to the latest Times story, the complete memos were ultimately provided by an “American official” who believed Eikenberry’s grim assessment “was important for the historical record.”

That explanation, said Alexander Thier, the director of the US Institute of Peace’s Afghanistan and Pakistan program, doesn’t wash. “They want it to be part of the public record because of what motivation?” The leaker, he said, certainly wasn’t doing Eikenberry any favors. “There’s no question that whatever the motivation of the leaker or leakers they would have had to understand that this would have a damaging impact on Eikenberry’s ability to affectively fulfill his duties.”

Writing on Foreign Policy‘s web site today, Peter Feaver, a former National Security Council staffer during the Bush administration, said the leak indicated that the “the internal debate over Afghanistan is ongoing” and pointed to “serious problems within” Obama’s “national security team.”

Marvin Weinbaum, a scholar at the Middle East Institute and a former Afghanistan and Pakistan analyst in the State Department’s intelligence division, told me the disclosure of Eikenberry’s cables comes at a particularly “unfortunate” time for the Obama administration and provides more ammo to critics of his war strategy. “Right now we sort of thought we got past that debate and that we were on to the question of could we implement what we set out to do,” he said. “This just reopens the wounds from back in October and November when this debate was being had within the White House.”

Eikenberry’s memos expressed grave misgivings with components of the strategy Obama has now implemented. Among his chief concerns was that a large infusion of US troops would only make the Afghans dependent on American assistance. Outlining his case against a surge for Clinton, he said he feared this move would “deepen the military involvement in a mission that most agree cannot be won solely by military means” and “run counter to our strategic purposes of Afghanizing and civilianizing government functions here.” The troop escalation, he wrote, would result in making “it difficult, if not impossible, to bring our people home on a reasonable timetable.” The Obama administration, he added, had overestimated the ability of Afghanistan’s security forces to take the lead in securing their country by 2013. (In a hearing after Obama unveiled his strategy, Eikenberry said his reservations had been resolved and he was “100 percent” on board with the plan.)

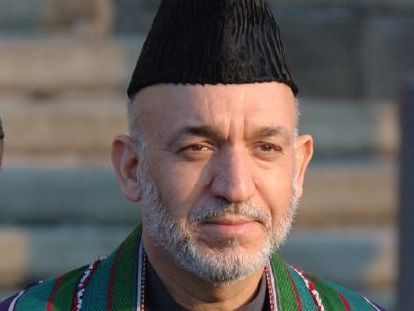

The ambassador was blunt about the main impediment to achieving the administration’s objectives: “President Karzai is not an adequate strategic partner.”

The proposed counterinsurgency strategy assumes an Afghan political leadership that is both able to take responsibility and to exert sovereignty in the furtherance of our goal) a secure, peaceful, minimally self-sufficient Afghanistan hardened against transnational terrorist groups. Yet Karzai continues to shun responsibility for any sovereign burden, whether defense, governance or development. He and much of his circle do not want the U.S. to leave and are only too happy to see us invest further. They assume we covet their territory for a never-ending ‘war on terror’ and for military bases to use against surrounding powers.

In Eikenberry’s judgement, “sending more combat forces will only strengthen his misconceptions about why we are here. Before any troop announcement, we should first have a high-level dialogue with Karzai and his new government to explain our goals and obtain agreement on what we expect from them. Even with such an understanding, it strains credulity to expect Karzai to change fundamentally this late in his life and in our relationship.”

Weinbaum said he was unclear on the purpose the leak was intended to serve, but believed it was damaging both to the Obama administration’s agenda and to the fragile relationship between Eikenberry and Karzai. “Just from the substance of his concerns, it says that the reason for our being there can be held hostage to the mal-administration, the venality, if you will, of the Karzai government.” He added, “Given Karzai’s personality, where he thinks that everybody is working against him, this is just so much meat for that… In no way can this be conceived as being constructive.”

Thier said: “The impact is damaging for Ambassador Eikenberry and his relationship to President Karzai and overall, possibly more broadly for US-Afghan relations depending on how these comments are seen.”

Speaking to reporters in Istanbul on Tuesday, Karzai responded, albeit obliquely, to Eikenberry’s criticisms. “If partnership means submission to the American will, then, of course, it’s not going to be the case,” he said. “But if partnership means cooperation between two sovereign countries, one of course very poor and the other very rich… then we are partners.”

Follow Daniel Schulman on Twitter.