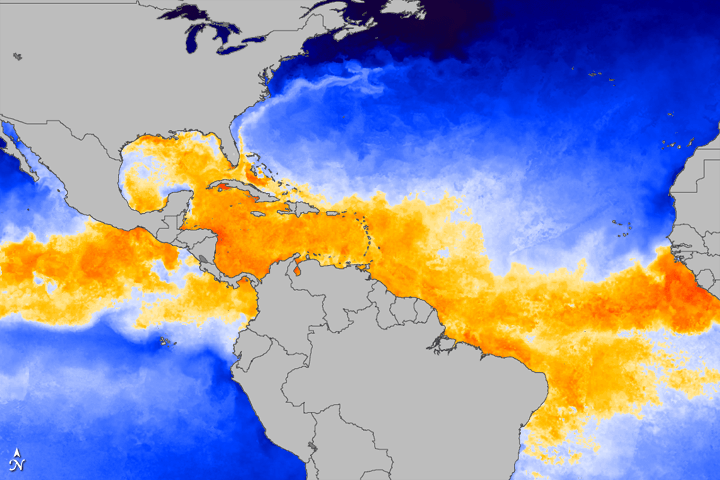

Image courtesy NASA Earth Observatory

NASA just released this graphic of current sea surface temperatures at the beginning of what looks to be an extremely active huricane season. The yellow and red colors denote waters already warm enough to foster hurricane formation. In the normal gestational cycle, the storms fuel up in the waters off Africa, where it’s already piping hot, then typically travel the warm water highway across the mid-Atlantic. As you can see, the waters of the Gulf of Mexico are primed with plenty of heat right now.

Here are a few salient points related to hurricanes and the BP oil spill, via NOAA’s Oil Spill response (pdf):

- The oil is not expected to appreciably affect either the intensity or the track of a fully developed tropical storm or hurricane.

- The oil slick would have little effect on the storm surge or near-shore wave heights.

- The high winds may distribute oil over a wider area, but it is difficult to model exactly where the oil may be transported.

- Storms’ surges may carry oil into the coastline and inland as far as the surge reaches. Debris resulting from the hurricane may be contaminated by oil from the Deepwater Horizon incident, as well as from other oil releases that may occur during the storm.

- The oil slick is not likely to have a significant impact on the development of a hurricane.

- Near the leaking well, where concentrations are heavy, a hurricane may pull deep-water oil to the surface, though probably not farther from the well head where oil concentrations in the water are lower.

- The experience from hurricanes Katrina and Rita (2005) was that oil released during the storms became very widely dispersed by the hurricanes.

- There will not likely be oil in the rain related to a hurricane since hurricanes draw water vapor from a large area, much larger than the area covered by oil, and rain is produced in clouds circulating the hurricane.