Greg Nash/WDCPIX.COM. Slider image via aagreverse.com.

For six years, former presidential hopeful Fred Thompson played Arthur Branch, the gruff, straight-shooting district attorney in the television series Law and Order. Thompson’s character had an unflinching commitment to the letter of the law. The same can’t be said for a firm that Thompson has been pitching for lately in TV ads: a mortgage company that’s landed in hot water in a half-dozen states for allegedly preying on elderly Americans and, in some cases, violating state law.

This spring, Thompson, a jowly ex-GOP senator from Tennessee, signed on to serve as the national spokesman for American Advisors Group (AAG). In an ad for the company, Thompson stands in front of a charming white house with an American flag flying out front and sings the praises of a lesser-known mortgage product called a reverse mortgage: “Join hundreds of thousands of other Americans who have used a reverse mortgage as a safe, effective financial tool,” he implores viewers.

Thompson’s new employer, however, has a troubled track record. Regulators in Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Virginia, and Washington State have cracked down on the firm for deceptive marketing and consumer fraud. In February, for instance, the Illinois attorney general, Lisa Madigan, sued AAG and its president for direct-mail solicitations that Madigan described as “extremely misleading.” That same month, the state of Massachusetts temporarily banned the company from doing business in the state.

A questionable company enlisting a popular public figure like Thompson to peddle its wares is nothing new. As Mother Jones recently reported, a company called Goldline International uses TV and radio host Glenn Beck to lure unwitting customers into dubious gold-buying deals. (AAG has also advertised on Beck’s Fox TV show.) Last month, JD Hayworth, a former Republican congressman who’s angling for Arizona senator John McCain’s seat, suffered a major embarrassment when an old infomercial resurfaced showing the conservative plugging $1,000 seminars on how to tap “free” government money.

In AAG’s case, putting a celebrity face on its mortgage products is at the core of the company’s marketing strategy. Before hiring Thompson, the company used the late veteran actor Peter Graves as its spokesman. And in August 2009, AAG president and CEO Reza Jahangiri explained that a large part of the company’s national marketing campaign would revolve around a “celebrity spokesperson” who “adds that credibility and gets borrowers a little more comfortable with the company.”

Reverse Mortgages: The New Subprime?

In AAG’s line of work, you need all the credibility you can get. The company peddles reverse mortgages, a variety of loan available to homeowners 62 or older, letting them tap the equity in their houses. Here’s how they work: In a typical mortgage, the lender advances the loan’s principal amount up front to finance the borrower’s purchase of a home, and then the borrower repays the lender in monthly installments. In a reverse mortgage, a lender like AAG pays a homeowner—either in monthly payments, a lump sum, or a line of credit—the amount of equity in the home. Then, as fees and interest accumulate over time on the loan, the borrower’s balance increases. That sum must be paid off when the borrower moves out, sells the home, or dies, at which point whoever inherits the house must pay off the loan.

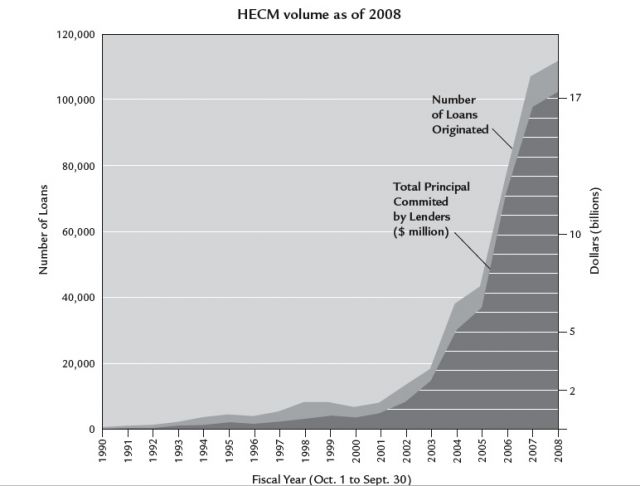

More than 90 percent of reverse mortgages are federally insured. Conceived in the early 1980s, they were envisioned as a way for the elderly to pull money out of their homes to pay for medical costs or supplement diminished incomes. In recent years, as the aging boomer generation swells the ranks of elderly Americans, the market for reverse mortgages has skyrocketed. The total principal committed in federally backed reverse mortgages increased seventeen-fold between 2001 and 2008, from $1 billion to $17 billion. Heavyweight banks like Wells Fargo and Bank of America, as well as lesser-known lenders like Financial Freedom, are all major players in the industry. And, like subprime mortgages, reverse mortgages have been securitized and traded, a practice that began for this lesser known industry in 1999.

Source: National Consumer Law Center, Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentAs the reverse mortgage industry grows, so, too, do the cases of fraud and predatory practices. In fact, the reverse mortgage industry today looks a lot like the subprime mortgage industry five or six years ago. According to a report by the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC), senior citizens are often pushed into reverse mortgages they don’t want or need by overzealous brokers, some of whom worked as subprime mortgage brokers before that market imploded. The Senate Special Committee on Aging has held two hearings, in December 2007 and June 2009, on the risks of reverse mortgages. At a June 2009 banking conference, John Dugan, the Comptroller of the Currency, warned (PDF), “While reverse mortgages can provide real benefits, they also have some of the same characteristics as the riskiest types of subprime mortgages—and that should set off alarm bells.”

Source: National Consumer Law Center, Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentAs the reverse mortgage industry grows, so, too, do the cases of fraud and predatory practices. In fact, the reverse mortgage industry today looks a lot like the subprime mortgage industry five or six years ago. According to a report by the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC), senior citizens are often pushed into reverse mortgages they don’t want or need by overzealous brokers, some of whom worked as subprime mortgage brokers before that market imploded. The Senate Special Committee on Aging has held two hearings, in December 2007 and June 2009, on the risks of reverse mortgages. At a June 2009 banking conference, John Dugan, the Comptroller of the Currency, warned (PDF), “While reverse mortgages can provide real benefits, they also have some of the same characteristics as the riskiest types of subprime mortgages—and that should set off alarm bells.”

Lenders target seniors by advertising on TV, via the Internet, and through direct mail; in some cases, they disingenuously describe reverse mortgages as “free money,” and ply seniors with images of shopping sprees and dream vacations. In AAG’s case, the company’s marketing materials are at the heart of its run-ins with state regulators.

In September 2008, regulators with Massachusetts’ Division of Banks ordered AAG to stop sending “false or misleading” direct mailers to consumers, which strongly resembled official government mailings. The company agreed. Seven months later, though, state regulators again caught AAG using misleading mailers that suggested the company’s reverse mortgages were related to the Obama administration’s economic stimulus plan—which wasn’t true. Massachusetts regulators also said that the fine print on AAG’s offer was printed in a smaller font and a lighter color so that it was especially hard to read. In February 2010, the state banished AAG from doing business in Massachusetts for nearly two years.

AAG has had similar run-ins with regulators in Washington, Illinois, Virginia, Florida, and Maryland. Washington regulators found that AAG sent the deceptive mailers to approximately 72,000 state residents, violating state law. In Virginia, AAG settled with the state and paid a $7,500 as a result of its deceptive marketing materials, though the company admitted no wrongdoing. And in Wisconsin, the state’s banking division cited AAG for failing to fully disclose its conflicts with Massachusetts and Washington regulators while applying for a mortgage banking license, for which the company paid Wisconsin $2,000.

AAG says its deceptive mailers were the work of a third-party marketing company and not the company directly. Since running into trouble with state regulators, the company “realized the need to be in control of our marketing and the need to be very conservative in our approach,” CEO Jahangiri told ReverseMortgageDaily.com. The company has also pursued settlements and other compromises with state regulators in response to issues arising from its mailers, state regulatory records show. Jahangiri didn’t respond to questions submitted in writing by Mother Jones for this story.

Fred’s Spotty Spokesman Record

AAG announced Thompson’s new role as pitchman this spring, amidst the crackdown by state regulators. (Thompson, through the public speaking agency that represents him, did not respond to a request for comment.) Now, his face is plastered all over AAG’s website and marketing materials. His signature even adorns the company’s front page. “Find out how much cash you may qualify for,” Thompson says in his AAG ad. “Call AAG today.”

This isn’t the first time Thompson has lent his name to a questionable company. He is among conservative luminaries like Glenn Beck, conservative radio host Laura Ingraham, and former presidential candidate Mike Huckabee who’ve worked as paid spokespeople for Goldline, the gold company that’s been accused of scamming its customers.

In 2007, Thompson, then mulling his presidential run, appeared in radio ads for a fraud prevention company named LifeLock. That company’s owner, the Los Angeles Times reported, had previously been accused by the Federal Trade Commission of deceptive advertising and stealing money from customers’ bank accounts. (The owner, Robert Maynard Jr., settled both accusations without admitting wrongdoing, but was banned by the FTC from selling “credit-improvement services.”) A Thompson spokesman said at the time that Thompson hadn’t researched the company beforehand, and that the voice-over was part of Thompson’s contract as an ABC Radio commentator. “You can’t expect the individual on-air personality to do research on every company,” the spokesman, Mark Corallo, said.

*****

Read the State of Illinois Attorney General’s complaint against AAG: