Photos: Matt Nager

[Editor’s Note: See a related photo essay here.]

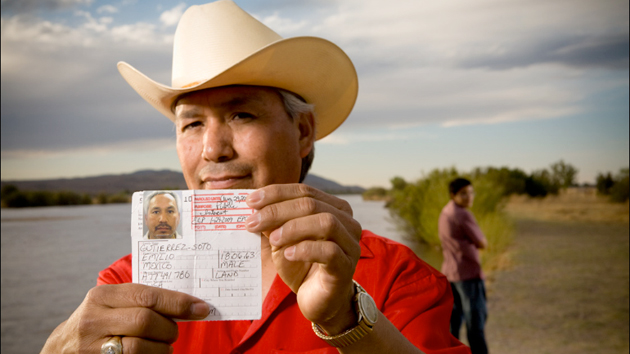

AGENT GUERRERO’S radio scratches to life: Are you at the bodies yet? In local Border Patrol lingo, the word for border crossers is the same whether they’re living or dead.

Yep, we’ve got four of them, he radios back.

We’re crawling along a dusty desert road in Guerrero’s Chevy Tahoe, 65 miles southwest of Tucson and miles from anything with a roof and a door. From the sky we must look like a toy army truck, dwarfed by our rust-tinted surroundings—rocks and clay, cacti and mesquite. Guerrero is explaining how easy it is to die out here. “People don’t understand how grateful people are to be caught. Depending on where the group crosses, it’s almost impossible to carry the amount of water they’re going to need,” he says. “And during the summer months, there’s absolutely no shade.”

We find these bodies in a valley in the San Luis Mountains, 11 miles north of the border. We know their names because we asked them: José Luis Aquino Garcia, 26; Lorena Márquez Ramirez, 25; Eduardo Cardoso Delgado, 34; and Jhoana Stephany Hernandez Márquez, 8. It’s harder to find names for the other kind of bodies.

As many as 700 corpses of migrants are found in the deserts and mountains of US border counties each year. Roughly half are anonymous. Undocumented border crossers travel light, sometimes leaving nothing to identify them if they die. It doesn’t help that their bodies are often unrecognizable; by the time they’re found, hungry javelinas and coyotes have carried away their organs. Sometimes their skin, and with it fingerprints and birthmarks, is long gone. Often their bones are bleached white from the 100-degree sun.

A dead body without a name can’t be buried, not in good conscience, at least, until efforts to identify it seem completely hopeless. And each person who deals with border bodies has a different definition of hopeless. That’s the Juan Doe problem.

A popular migrant crossing area near the Pima County border.

A popular migrant crossing area near the Pima County border.

THE PIMA COUNTY Office of the Medical Examiner is a small, poorly marked cinderblock building in a suburban stretch south of Tucson. It could be mistaken for a dentist’s office if not for the ominous fleet of white vans parked in the rear.

Inside, chief medical examiner Dr. Bruce Parks sits behind a U-shaped wooden desk, empty but for some Post-it notes, a microscope under a plastic cover, a Dell computer, and a few photographs of his kids. He’s tall and plainly dressed, with a kind face, a receding crown of gray hair, and a paternal awkwardness that probably comes from talking about unpleasant stuff all day. He seems tired and a little sad.

At 9,186 square miles with 126 miles along the border, Pima County has a high rate of crosser fatalities. But Pima’s failure rate in identification is lower than others, largely because its examiners have had a lot of practice.

Parks pivots his office chair toward me and tries to pinpoint the moment when death in the desert became his life.

“The whole thing started in 2001, the year those 14 died,” he says. “Twenty-eight people had been crossing in a group, and they got lost; basically, they were led astray, and 14 of them died. All 14 came here.”

He is referring to the Yuma 14, a case immortalized in Luis Alberto Urrea‘s book The Devil’s Highway. Urrea visited Pima County, where he saw photos of the bodies:

A shrine near Arivaca, Arizona, honors dead crossers.

A shrine near Arivaca, Arizona, honors dead crossers.

The dead have open mouths and white teeth. They are stretched in angular poses, caught in last gasps or shouts, their eyes burned an eerie red by the sun. Many of them are naked. Some of them have dirt in their mouths. When the corpses are those of women, their breasts have shrunk and withered and cracked open under the sun…For many of them, these are the first portraits for which they have posed.

“It was a big shock to the office,” Parks continues. “I think it was then we realized we might be in the midst of something.”

Dozens of bodies soon became the norm. In 2005, the Pima County ME received 69 in one month, forcing the office to rent a refrigerated 16-wheeler for $900 a week to house the remains until they could be identified and released for burial.

Parks turns to face his computer screen. He’s offered to show me a PowerPoint presentation he gave at a recent conference. It will include some photographs of the dead: a man wearing gray slacks and one sock, lying under a mesquite tree; a mummified corpse missing skin on its lower back; a roasted-looking body on an autopsy table.

“Hopefully these images won’t bother you too much,” Parks says soberly, glancing over to see if I object. “If you don’t like what you’re looking at, just look away.”

Next door is the building that houses the examination room—cool metal surfaces, and a white wall with several huge rectangular dry-erase boards, on which a tic-tac-toe grid of numbers is outlined variously in black, blue, and red ink.

“These boards reflect the bins, the spots, the spaces that each person occupies,” Parks says, referring to the way the morgue is organized into rows of metal drawers. “So for every number you see within a grid, that’s a person.”

There are hundreds of boxes in the grid, some of the numbers filled in thickly in black, others smudged in places, perhaps nudged by a clumsy finger. Seventy-eight of the numbers represent border crossers.

Some boxes contain more than one set of numbers. Those remains are skeletonized, Parks explains, which means more than one person can fit in each drawer.

Next, Parks leads me to the windowless “property room,” where the valuables of the dead are stored in filing cabinets. He slides open a John Doe drawer and removes a pile of clear plastic envelopes. He begins a litany of the contents.

“Earrings, prayer cards—that’s pretty common—wallet. Yeah, it’s pretty sad. Some American coins. A radio. You can see their things are discolored because the body’s decomposed, and it probably doesn’t smell too good.”

My eyes gravitate to a black cotton scrunchie, flattened within its plastic enclosure, still wearing a few bits of desert debris and one long black hair. It’s such a simple domestic artifact, ubiquitous in women’s bathroom drawers. I imagine a young woman who tied her hair back the day she left for the desert with some strange coyote. If her case was typical, she wasn’t told it would be an arduous several-day trek, but maybe a two-hour walk, no big deal. She may have worn her Sunday clothes.

After walking for five days with little water, this crosser was unconscious when a ranch hand found him near Green Valley, Arizona.

After walking for five days with little water, this crosser was unconscious when a ranch hand found him near Green Valley, Arizona.

Parks waits as I take a quick photograph. Then he closes the drawer.

THE JUAN DOE problem first came to my attention through Chelsey Juarez, a graduate student in physical anthropology at the University of California-Santa Cruz, who has agreed to let me shadow her at the lab.

Today, she wears a white lab coat and tight blue surgical gloves, a long braid hanging over her left shoulder. She’s wide-eyed and pale-skinned, her face lit by dangly earrings, a rare splash of color in this stark white room.

She sits down in a ratty desk chair and scoots it toward the drill she’ll be using to separate the dentin from the enamel of an anonymous human tooth.

“Some days I spend 12 hours straight staring into this thing,” she says, leaning forward so her eyes are obscured by the rubber viewfinder. “We call it the death chair.”

Under the microscope, the cross-sectioned molar appears inside a circle of light, like a corn kernel drained of its color. Juarez points out the dull, porous inside area of the tooth. “That’s the dentin,” she says. Extracting the dentin is the first step, but what Juarez is ultimately looking for exists on an even smaller scale: the element strontium.

Strontium is key in solving archaeological puzzles because it is one of the most geographically traceable elements: It originates in bedrock, and each type of regional rock contains a unique ratio of strontium isotopes. That isotopic ratio acts as the rock’s signature—it gets passed on to the soil above and ultimately into the plants that are grown there. When people eat those plants, their bodies incorporate that same ratio into their bones and teeth. While strontium in bones can fluctuate throughout people’s lives, its levels in molars are fixed in childhood, so our teeth can serve as a sort of treasure map, leading to where our food was grown when we were young.

For most Americans, that doesn’t mean much: We grew up eating apples from New York, lettuce from California, and corn from the Midwest. But in the regions of Mexico responsible for the highest numbers of migrants—Guanajuato, Oaxaca, Sonora, Chiapas, and Michoacán—most people still raise their own chickens and shop at the regional produce market. Which means their teeth might be able to tell us where they’re from.

With two hands, Juarez positions the tooth below a long, thin metal drill bit and rotates it to the front. Applying slight pressure to a foot pedal, she starts the drill, and it burrows in, stirring miniscule bits of dentin into the air like leaves in a mini-whirlwind. The bits float slowly down onto a thin white tissue below, which Juarez folds, and tips into a tiny transparent vial.

Juarez is creating a map of isotopic signatures throughout Mexico. To do this, she needs to gather tooth samples from all over the country, which has proven more difficult than she initially thought.

A Tucson funeral-home worker prepares an unidentified body for burial.

A Tucson funeral-home worker prepares an unidentified body for burial.

At first, Juarez tried getting teeth from dental clinics in Mexico. But only wealthy Mexicans get dental care. And wealthy Mexicans eat like Americans; their teeth would simply say: supermarket. She had better luck once she began visiting US dental clinics that cater to immigrants. These patients, she figured, had crossed the border at some point and survived. Perhaps the teeth of the living could bring dignity to the dead.

The tooth Juarez just finished drilling arrived in a tiny plastic bag from a dental clinic in nearby Half Moon Bay, where immigrant patients having teeth pulled can contribute their teeth to Juarez’s project. A label on the bag reads:

Hometown: Jalisco, MX

Did you move as a child?

_Yes _xNo

Sex: _F _xM

Once the tooth’s enamel has gone through all the steps of analysis—from an acid cleaning process to drying, crushing, “digesting,” freeze-drying, and then hurtling at high speeds through a mass spectrometer—Juarez will plot its isotopic signature on a map of Mexico. Once the map is complete, Juarez hopes that labs will be able to compare isotopic signatures in unidentified border crossers’ teeth to those on the map to find out where the crosser grew up. Imagine those new points, then, as an overlay: the topography of poverty, the landscape of leaving home.

Juarez’s father was an immigrant. He entered the country when he was 15, along with his grandmother, sister, and brother. Juarez has always been interested in border politics, but in college she realized she wanted to be a scientist. The challenge was to do work that felt relevant to the Latino community.

“I believe in doing science for the people—breaking out of academia and doing work that’s useful,” she says. “And even if you don’t think undocumented people should be here, you can agree that dying in a strange country, and losing touch with your family, that’s a tragedy.”

Juarez and I relocate to the Earth and Marine Sciences building, home of the Neptune, a hunk of stainless steel and white painted metal that looks like a high-tech copy machine turned inside out. Juarez will insert the processed tooth samples into the Neptune, and it’ll spit out the isotopic ratios.

Over the roar of the ventilation, I ask Juarez what her colleagues working in border forensics think of her work. They were wary at first, she explains. In 2004, Juarez attended a forensic symposium in Dallas, which focused on migrant death. There she met some of the primary people working on the issue of border death, including Parks and his colleague, Bruce Anderson, a forensic anthropologist.

“They weren’t exactly like, ‘Let me take you under my wing,'” she says. “But you know, they’ve been burned.”

Juarez is referring to an incident from several years ago: The office of the Pima County ME was threatened with a lawsuit by the son of a deceased woman whose body was buried without the brain, which was still soaking in formaldehyde. Parks has learned to be particularly protective of all the human materials under his care.

Chelsey Juarez in the lab where she’s been tracing the origins of migrants’ teeth since 2005.

Chelsey Juarez in the lab where she’s been tracing the origins of migrants’ teeth since 2005.

When I asked Parks about his initial reluctance to work with Juarez, he replied that his loyalty is to the families of the deceased.

“If a technique is helpful, then we’ll do all we can to help,” he said. “But I can’t just be giving body parts to people for research. We have to remember that even if these [bodies] are unidentified, they’re still people—they still have families.” Of late, however, the Pima County crew has become more receptive to Juarez’s work; they have also worked with a molecular anthropologist at Baylor University on a DNA database that tries to match unidentified remains with family members searching for loved ones.

The spectrometer is churning out paper now, each white sheet printed with line after line of numbers extending to the umpteenth decimal point. All of these isotopic ratios will go on her map of Mexico. For it to be truly complete, she’ll need many more teeth than she’s analyzed so far—especially from regions where her data is still thin.

“I will probably be working on this for the rest of my life,” she says. “It’s a lifelong project, a life’s work.” She pauses, considers what she’s just said, and adds, “Sheesh.”

THE OFFICE of the Pima County ME has a reputation for taking great pains to identify bodies—and in 70 percent of cases, it succeeds. But sometimes pursuing long-shot leads takes years and still it comes up short. Then the dilemma is transferred to Raymond Rodriguez, who handles “indigent burials” for the county, which means he buries prostitutes, bums, and anyone else whose family doesn’t know they are dead, or who left no one willing or able to pay for their burial. In their home countries, few border crossers would fall into this category—most have migrated precisely to support the many people they’ve left behind.

Rodriguez has a thick head of gray hair and dresses like a high school principal: crisp collared plaid shirt, pleated navy-blue pants. I’ve asked him to accompany me to Evergreen Cemetery, a small out-of-the-way portion of which is reserved for the burial of indigents. We meet in downtown Tucson and drive north until the mattress superstores and taco joints of the exurbs begin to melt back into desert.

To get to the potter’s field, we pass through the private burial areas within the cemetery, where scrubby green trees cast shade over sturdy engraved headstones. Those areas are lush compared to the indigent section, a wide-open stretch of bare soil, naked to the midday sun. Here, the headstones lie flat—some are plastic, some stone—a few of them crowded with tacky silk flowers and portraits of the Virgin Mary.

Body bags, many holding unidentified bodies found in the desert, sit in a cooler at the Pima County ME office.

Body bags, many holding unidentified bodies found in the desert, sit in a cooler at the Pima County ME office.

Rodriguez clasps his hands at the small of his back, a few strides behind me, as we begin to pace the rows. He explains that the funeral home they contract with has to use concrete liners for the graves, because the desert soil shifts with the winter’s flash floods. Right then I notice a sinkhole where a headstone should be—the grave marker has sunk nearly a foot below ground.

“Rainy season in Arizona is pretty much mid-June through mid-September, and it really sinks the ground,” he says. “But this is tax dollars, and if you don’t have enough tax dollars you can’t keep up with the private cemeteries.”

There aren’t many Juan Doe graves here more recent than 2004—that’s the year Arizona amended a law to allow Pima County to begin cremating anonymous remains.

Rodriguez is proud to show me a better-groomed part of the indigent section—the columbarium, where cremains are stored. Rodriguez’s boss pushed hard for the funds to build it, and the dust of construction has barely settled. Simple stone plaques mark the openings where urns will be placed—about a dozen per slot, Rodriguez says.

As we gaze at the rows of plaques, I ask Rodriguez whether a sense of tragedy ever overwhelms him.

He glances back toward the older part of the cemetery, where rows of gravestones, like tree rings, mark the passage of years. “These people are transient because of work—because of a lack of work in their country,” he says. “And if in that process someone loses their life, we still need to maintain their dignity and take care of that loved one. Because you come from somewhere. You have family somewhere. That’s what I believe down deep, and that’s what moves me to do what I do.”

Next to the engraved plaques, the rest of the stones wait expressionlessly, like faceless mannequins in a department store display. I ask Rodriguez what the unknowns’ plaques will say.

Bones of a presumed crosser discovered near Tucson by a woman on horseback.

Bones of a presumed crosser discovered near Tucson by a woman on horseback.

“We may not engrave the John Does,” he says. He shakes his head. “To me, initially, I thought—gosh, they need to be respected, but by the same token, it would save us some money not to engrave the John Does—and what for?”

BACK AT HIS Chevy Tahoe, Agent Guerrero has guided the four migrants into the backseat and handed them a jug of water. They’re thirsty, but otherwise they look pretty healthy. Luis, the 26-year-old, still smells faintly of cologne.

Guerrero asks how long they’ve been out there. Four days, they say. Guerrero smiles sympathetically, and asks, “Que pasó?” What happened?

We were part of a group, Luis explains. My wife couldn’t walk any farther, so we asked if we could rest and the coyote said no. He told us to walk for two hours in that direction, where we’d reach a road and we could flag down somebody and turn ourselves in.

But they walked for two days and saw no one, no cars, nothing. They’d filled up their water jugs from a cattle trough, he said, and slept under a mesquite tree. They’d been worried about being eaten by coyotes, the animal kind.

Guerrero says the situation is classic. When border crossers get into trouble, it’s frequently because they separated from a larger group, the coyote telling them they’ll be fine if they just walk that way for a little while. Luckily, in this case, Luis had a cell phone, so they called the Mexican equivalent of 911, which called the US Border Patrol, which dispatched Guerrero.

Some days, Guerrero is out on rescues, like the one I tagged along on today. Other days he stalks around like a crime detective, following trails of footsteps and bits of torn clothing on barbed wire fences, trying to find migrants whose compañeros had to leave them behind. The father or friend of the person will finally make it to a road, flag down an agent, explain where they left the person, and ask for help.

“Picture this,” Guerrero explains. “You finally make it to the point where the person is supposed to be. And now you see this set of footprints that’s walking away from that spot. They’ve told you everything—’The person is under a tree, we laid a blue shirt on top, they have an orange backpack’—and you confirm that this is the spot because you see the orange backpack and you see the blue shirt up on a tree and you see that the person started walking, and you’re like, okay, this isn’t good.

“You start seeing the person is going left and then a hard right, and then left, and then you see them kind of make a circle. And you know exactly what’s going on. And you keep walking and now you’ve found a belt. And you keep walking and you find a wallet and…shoes. I mean, you’re starting to picture this person—they’re, they’re…they’ve lost it. Their mind is gone. And they’re just aimlessly…just walking. And you know that when you get to them, they’re going to be dead.”

Guerrero’s gaze is still fixed on the road.

Anonymous graves for border crossers at Pima County’s Evergreen Cemetery.

Anonymous graves for border crossers at Pima County’s Evergreen Cemetery.

“And sure enough, once you find them, they have cholla [cactus] all over their mouth and hands. And they’re already on the ground, and rigor mortis has set in. They’re starting to balloon up and decompose because of the heat. And you can only imagine how much these people suffered. How much they suffered.”

Guerrero has seen a lot of dead people in the course of his work. And he’s picked up a lot of living people who don’t have long to go. He says he can tell if a person thinks they’re going to die.

“You can see the look of doom in their expression,” he says. “You know your body. And you know when you’re…almost going to go.”

I think about the four “bodies” in the backseat. They’re dazed, thirsty, disappointed, but certainly not prepared to die.

Most likely they’ll try again.