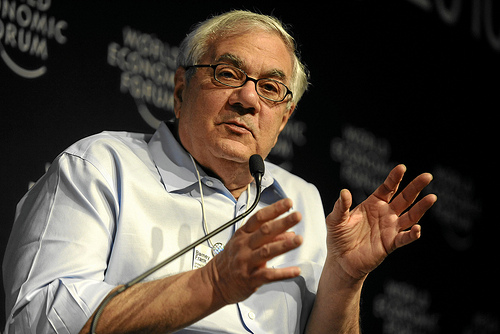

Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/thenails1/3407072012/in/photostream/">thenails</a>

The chairman’s seat on the House financial services committee ranks among the most coveted and powerful perches on Capitol Hill. Consider Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), the committee’s outgoing chief. As chairman, the smart, sharp-tongued Frank served as point man in Congress on the passage of TARP, the much-maligned bailout helped avert a second Great Depression. He also crafted and shepherded from inception to final passage this year’s financial regulatory reform bill, hence the legislation’s unofficial name: Dodd-Frank.

Already a power struggle has broken out between two GOP congressmen, Spencer Bachus of Alabama and Ed Royce of California, to claim the chairman’s gavel when the Republicans assume control of the House in January. That Royce is challenging Bachus at all shows the jostling underway to take power in the upcoming 112th Congress. Bachus, of course, is the obvious choice to become chairman, having served as the financial services committee’s ranking member. Royce, meanwhile, ranks fourth among Republicans on the committee.

While both men have downplayed the drama for winning the gavel, there’s plenty at stake here. For Bachus, dumped unceremoniously from the GOP team that took part in crucial bailout negotiations in 2008, winning the chairmanship would mark a return to the top financial seat in his party. A Royce victory, leapfrogging as he would two other Republicans on the committee, would swiftly launch him into upper rungs of House Republican leadership.

For consumer advocates and pro-reform types, there’s no favorite in the Bachus-Royce race. Both are freemarket-loving lawmakers who want to dismantle, if not wipe out altogether, the new financial regulatory reform bill before it’s even drawn first breath.

Let’s start with Bachus, the sandy-haired, 62-year-old congressman from central Alabama. A quick glance at Bachus’ campaign coffers and donors shows that he’s a Big Finance favorite. During his nine terms in Congress, the top five industries giving to Bachus all hail from the financial world: commercial banks ($1 million), insurance ($818,850), real estate ($773,651), securities and investment ($686,116), and finance/credit companies (410,508). His top contributors include JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and the National Association of Realtors.

With the passage of the Dodd-Frank bill, Bachus’ relationship with Wall Street has only tightened. In October, as Politico reported, he chided a group of 100 financial lobbyists at the Capitol Hill Club, a popular GOP haunt, for their disproportionate giving to Democrats, who lead the reform effort. As it happened, Wall Street heeded Bachus’ plea: In the 2010 midterms, the finance, insurance, and real estate, or FIRE, sector gave a higher percentage of its total donations to the GOP than in the previous two elections.

That cozy relationship in mind, it’s hardly surprising to learn that Bachus wants to roll back key parts of Dodd-Frank. For instance, the Alabama congressman said in September that he wanted to repeal federal regulators’ new power to wind down and liquidate “too big to fail” banks whose collapse could topple the financial system. (Think Citigroup, circa October 2008.) Bachus believes Dodd-Frank’s too-to-big-fail provision will only make bailouts permanent, not end them; instead, he wants to rewrite the bankruptcy laws to handle major bank failures.

Bachus also has in his crosshairs the “Volcker Rule,” which would stop banks’ “proprietary trading” (risky trading for their own benefit instead of for clients’); limit their stakes in riskier outfits like hedge and private equity funds, where regulation is lighter; and limiting how much domestic banks can expand within the US. House and Senate Democrats overwhelmingly support the provision, and former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker himself wants as broad an interpretation of the rule as possible. Yet Bachus has repeatedly attacked the provision. During the bill-writing process, he tried and failed in adding an amendment blocking the Volcker Rule’s implementation until other countries put in place their own prop trading bans. And in a recent letter (PDF) to financial regulators, Bachus said the Volcker Rule would “impose substantial costs on the American economy and market participants” with “doubtful” benefits.

On the issues, Ed Royce, who represents southern California’s Orange County, isn’t all that different from Bachus. He, too, has benefitted from Wall Street’s largesse. Three of the top five industries who’ve donated to Royce over his career come from the finance industry, including the insurance ($665,530), real estate ($561,950), and securities and investment ($430,350) sectors.

Like Bachus, Royce is no fan of Dodd-Frank, and would, as chairman, seek to chip away at the bill. For starters, he wants to give bank regulators veto power on the rule-making abilities of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. There’s just one problem with that: The consumer bureau is already subject to veto by a two-thirds vote from the Financial Stability Oversight Council, a new council of regulators tasked with preventing banks from becoming too big to fail. Elizabeth Warren, the Harvard law professor who conceived of the bureau and is now tasked with getting it off the ground, responded on Monday night to statements like Royce’s to undermine the bureau. “I’m really surprised by this move,” she told MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow. “Following the Great Depression, it took fifty years before anyone started chipping seriously away at the new reforms that had been put in place to protect us. Now, here we hope we’re coming out of another great recession, we’ve passed serious reform, and it’s just a matter of months until people are talking about how to undercut this new consumer financial protection agency.”

Royce has said he wants to rewrite the section in Dodd-Frank dealing with derivatives, the complex financial products that mirror the value of real goods (oil, corn, wheat) and, before the financial crisis, were used to make risky bets on the fluctuations in financial markets. Dodd-Frank requires most derivatives, or “swaps,” trades to be processed through a central clearinghouse, and requires both speculators and possibly “end-users”—the utility companies, farmers, airlines, and more using derivatives to legitimately hedge against risks, like fluctuations in oil prices—to post collateral in case trades go bad. While potentially increasing the cost of hedging, these reforms will beef up stability and safety in the derivatives markets. Royce, however, has suggested he would amend the derivatives part of Dodd-Frank to let non-financial companies using derivatives off the hook, even though the Congressional Research Service found that such an exemption would all but nullify the rule.

Where Royce has been especially vocal is on the fate of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two taxpayer-owned government housing corporations. Royce believes the popular Republican talking point that Fannie and Freddie are “the two institutions most responsible for the collapse of the housing market,” even though ample evidence disproves that theory. As chairman, Royce would tackle the question of either reforming the housing giants or abolishing them altogether.

The most pronounced difference between Bachus and Royce is not their financial philosophies, but their demeanors. While Bachus struggled as ranking member to match Barney Frank’s blistering rhetoric, Royce showed no hesitation to lock horns with the Massachusetts Democrat. During the reform bill’s reconciliation process, Royce repeatedly clashed with Frank on the absence of any reforms for Fannie and Freddie. Royce’s willingness to trade barbs is likely one of the main reasons his challenge to Bachus’ seat has made headway at all.

In the end, though, the House financial services committee will see a major rightward shift with either Bachus or Royce as chairman. Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), a free marketeer who said the consumer bureau “assaults the liberties of the consumer,” is poised to take over the financial institutions and consumer credit subcommittee, while libertarian Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas), who wants to abolish the Federal Reserve, will likely take over the domestic monetary policy and technology subcommittee. And if that didn’t spell trouble for Dodd-Frank, the House GOP’s pledge to defund the financial reform bill makes plenty clear where Republicans stand on financial issues.