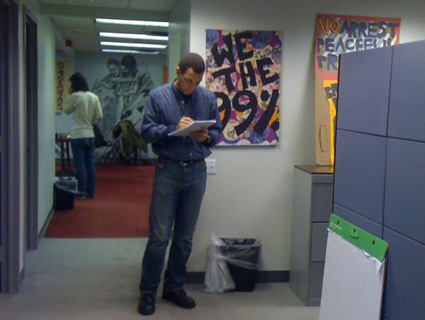

Protesters occupy a Bank of America branch in downtown San Francisco, California. See the rest of Mother Jones photo editor Mark Murrman’s photos of the incident here.

Protesters occupy a Bank of America branch in downtown San Francisco, California. See the rest of Mother Jones photo editor Mark Murrman’s photos of the incident here.

What will the evicted residents of Zuccotti Park occupy next? Will it be Duarte Plaza, a triangular patch of brick and gravel owned by Trinity Church in Tribeca? Foreclosed and abandoned buildings in Harlem and the Lower East Side? Nearby colleges or small towns? Or something less tangible?

At a 40-person meeting Saturday to discuss the issue, not everyone thought that retaking a public space would be worthwhile. “Not to sound like an asshole, but there’s a lot of energy and resources that go into sustaining an occupation and feeding and clothing people,” said Daniel Zeta, a respected former resident of the park. “If we are not careful, we are going to turn into a homeless shelter and food kitchen, and to be honest, that’s not why I came here.”

Others argued that OWS has a duty to revive the country’s first and most symbolic occupation. “Having a space that is a show of force, that is big, that is in your face is really important,” said a guy named Danny, clad in a red bandanna and plaid shirt. “And it’s something that a lot of different occupations around the country are waiting for us to do.”

Even before last week’s police raid and eviction of campers from the park, the movement’s organizers were working to set up satellite occupations around the city. On October 15, the night of a massive demonstration at Times Square, a delegation from Zuccotti held a 3,000-person rally at Washington Square Park near New York University, where they announced they would camp. But just before the park’s midnight curfew, about 100 riot police dispersed the crowd and arrested 14 holdouts.

“Washington Square is a hard case because it is a public space and there are laws that protect that space,” says Sandy Nurse, a key organizer with the OWS Direct Action Working Group. “The idea of an occupation is obviously to hold it and grow it, and it can’t help when you are constantly under threat from being evicted and beat up by the cops.”

Duarte Plaza: Ask Now, Take Later?

After Washington Square, organizers began looking for other spots in Lower Manhattan that, like Zuccotti, were privately owned public spaces not subject to New York City’s curfew laws and camping restrictions. About a week and a half ago, they began putting out feelers to Trinity Church, one of the city’s largest private landowners, about occupying the vacant lot it owns at Duarte Plaza. Trinity had already given OWS free meeting spaces in its buildings near Wall Street, but church leaders drew the line at hosting a new encampment. After talks broke down, organizers decided to move ahead with the Duarte occupation anyway.

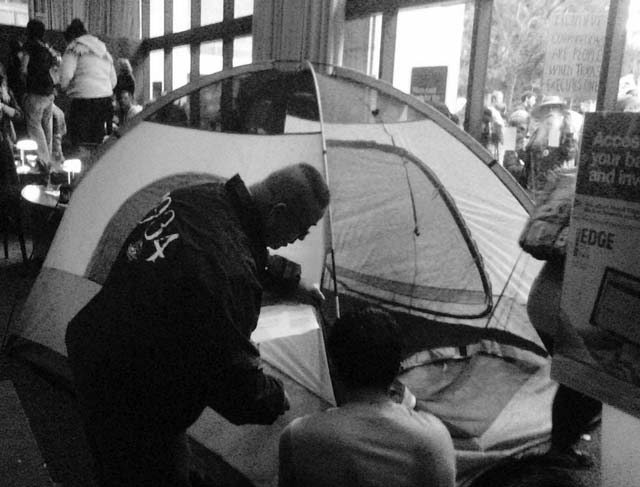

A date was set for Tuesday, November 15—the same day, it turned out, that police evicted the campers from Zuccotti. “And then it was like, ‘Okay, let’s go for it,'” Nurse recalls. A couple hundred people amassed at the plaza that afternoon along with supportive religious leaders from other churches. But Trinity wouldn’t cave to the pressure. After occupiers cut into the chain-link fence around the lot, church leaders allowed the police to disperse the crowd, arresting about 10 people.

Three days later, OWS organizers began planning a different approach. They met with religious and civil rights leaders this past Sunday at Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square, and then peacefully marched to Duarte holding candles and illuminated tents bearing slogans, including: “You can’t evict an idea whose time has come.” They softly sang old labor and civil rights songs such as “We Shall Overcome” and “This Little Light of Mine.”

“We came to declare our solidarity with this movement,” said Rev. Nelson Johnson of Greensboro, North Carolina, an elder of the civil rights movement, as he marched down 6th Avenue. “I think it represents maybe the greatest possibility that we’ve had in the past 20 years of making some changes that are so desperately needed in our financial institutions, and in just the respect for the dignity and worth of life. All of the forces and factors that have pushed against that have to get changed.”

When the march arrived at Duarte, activists covered the wall surrounding the Trinity lot with construction paper and wrote messages imploring the church to reconsider its stance on the occupation. “Trinity, please share your space with the rest of humanity,” one message read. Another added: “Please contribute what you don’t use to those who need it.”

To be sure, Trinity has reason to balk at becoming OWS’ new landlord. Zuccotti Park in its final days had become overstuffed with tents, beset by thieves and drug dealing, and overburdened by the need to clean up after itself and administer to a growing population of chronically homeless and mentally disabled. While the decision of OWS to welcome the poor was certainly Christian, it was controversial even within the movement. Many occupiers worried that OWS didn’t have the resources to deal with the problems it attracted.

But Nurse and the would-be Duarte occupiers say they’ve learned from their mistakes. If Trinity allows the occupation, it will be protected from thieves by the surrounding fence. The only tents allowed inside will be large military versions that each sleep 18 people, allowing better oversight of campers and plenty of meeting spaces for daytime use. Anyone who wishes to join the occupation will be required to sign a pledge to actively participate, not use drugs, and keep the peace; those who don’t comply will be removed. And the Duarte occupation will have its own General Assembly composed entirely of occupiers, giving it much better control of itself.

“They need to trust that this generation can do things that are meaningful,” Nurse says. “You are banking on human beings. They are going to deliver if you just put a little faith in them—which you say you are supposed to be about. I mean, historically, churches have offered political asylum, and it’s important to realize that this is political asylum. We are trying to change something here.”

So far, however, none of this has been enough to bring Trinity around. “Occupy Wall Street does not have permission to enter the closed private portion of Duarte Square,” the church told me in a prepared statement on Monday.

The lot located one block north of the mouth of the Holland tunnel is inappropriate and potentially unsafe for large-scale assemblies. It has no facilities and has been made available on a limited basis for a seasonal outdoor art installation. Trinity supports the vigorous engagement of the issues raised by Occupy Wall Street and will continue to provide indoor meeting spaces and facilities at its locations in and around Wall Street during open hours

Nurse and her comrades are unbowed. “I do believe the next attempt will be a take,” she says, “whether we are given it and it being a nice action, or taking it.”

Teaming Up With the Squatters

This past spring, several months before Occupy Wall Street launched, a group of homeless advocates, a radical law firm known as Common Law, and veterans of New York City’s ’70s-era squatters movement formed Organizing for Occupation (O4O), a squatters’ group focused on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In July, O4O held a conference that brought in squatters’ groups from around the country. “From there we started recruiting for our teams,” says Luke, a young Bronx-based homeless-shelter worker and spoken-word poet who declined to give me his last name. “And now things are in action.”

Modeled on past squatters groups, O4O has organized into teams that specialize in finding abandoned buildings (research), breaking them open (crack teams), renovating them (construction), and finding people to inhabit them (intake). Luke says O4O has identified potential squats all over the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, but he declines to give a number for fear of attracting the authorities.

The group first gained attention in August, when a tiny, soft-spoken, 82-year-old named Mary Lee Ward faced eviction from her home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. In 1995, she’d taken out subprime loan from a lender that later declared bankruptcy after being investigated for predatory practices. O4O called out 200 people to form a human wall around her door. “If I’m evicted today, that’s it for anybody who is a senior citizen,” she told the New York Times. “It would show they can break up the community and do anything to us.” The city marshal who’d come to evict her backed down.

Then, in mid-October, O4O temporarily shut down a foreclosure auction in Brooklyn by standing up and repeating a song Luke had written:

Mr. Auctioneer

All the people here

We’re asking you to hold all the sales right now

We’re going to survive but we don’t know how…

Nine people were arrested before the sales resumed.

Not surprisingly, O4O and OWS have essentially merged. Occupy Wall Street has already planned a high-profile takeover of several buildings in Harlem on December 6. O4O prefers to work more under the radar, yet the evicted campers from Zuccotti Park have swelled its ranks. Some 150 people showed up at an O4O meeting on the Lower East Side Monday night, many of them occupiers who’ve been staying in nearby churches and want to be slotted into O4O teams. At the start of the meeting they chanted O4O’s slogan: “O4O is ready to act! We see you and we got your back!”

“Our common ground is both direct action and the firm belief that we want to challenge financial institutions that are robbing people of their lives, their homes, their dignity,” Luke says. “That’s the bottom line.”

Occupy Everything?

The Zuccotti eviction has given OWS a chance to export some of its energy to the rest of the country. Nearby Occupy New Haven, which is connected with Yale students, has made a longstanding offer to house the New York occupiers. And Daniel Zeta, the one who was skeptical of launching another occupation in Manhattan, would like to see his compatriots flock to Occupy DC, funneling their efforts into national political change. Sending protestors to other cities would also take some pressure off the two churches now housing a volatile mix of homeless people who’d flocked to Zuccotti park.

Veteran OWS organizers also want to arrange road trips to small towns across the country, bringing their anti-Wall Street message to Main Street and possibly launching new encampments. Occupy protests have already sprung up at whistle-stops like Littleton, New Hampshire, population 6,000, where people held “99 percent” signs on a street corner last week. (See our video of their protest here.) The road trips might also give weary occupiers a chance to get out of the big-city pressure cooker for awhile.

And there’s always Zuccotti Park. At a meeting of the Spokes Council, OWS’ quasi-governing body, someone announced an effort to coordinate reoccupation of the park in shifts to get around the prohibition on lying down there. There’s also been talk of serving Thanksgiving dinner at the park, an act of civil disobedience that would challenge the efforts of police to limit the distribution of food at Zuccotti. The jokes are already making the rounds on Twitter. As @Cosmik_ recently tweeted: “Who is basting their turkey with pepper spray this week? It is a food product, essentially.”