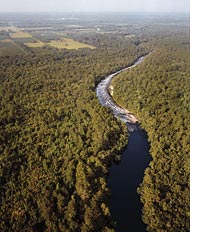

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/officiallouisiana/4716171712/">Louisiana Travel</a>/Flickr

You’ve probably heard of old-growth forests and their importance, but old-growth wetlands? A new study suggests that older wetlands, like ancient redwood groves, are more biodiverse and better at storing carbon than ones that have been restored. In a meta-analysis of 124 other studies examining 621 areas around the world, an international team of researchers found that restored wetlands contain about 23% less carbon than their predecessors and about 26% less variety in native plant life—even after 50 to 100 years of restoration. “Once you degrade a wetland, it doesn’t recover its normal assemblage of plants or its rich stores of organic soil carbon,” said study co-author Daniel Moreno-Mateos, a postdoctoral fellow at UC-Berkeley. This depletion, he added, will “affect natural cycles of water and nutrients, for many years.”

Although an estimated (PDF) half of the wetlands present in North America at the time of European settlement have been destroyed, more recent trends suggested a reason for optimism: the pace of wetlands loss has seemingly slowed drastically in the United States, dropping from a rate of nearly 500,000 acres a year from the 1950s to the 1970s to around 60,000 acres per year from 1986 to 1997. Some data even suggests there’s been a net gain since the late ’90s.

But this study could call cast a shadow on those strides: US policy is based on the principle of “no net loss,” which allows for development that destroys existing wetlands as long as its restoration or substitution is sufficient to leave total acreage unchanged. While this principle theoretically takes quality as well as quantity into account, in practice, there’s been little effort to track (PDF) wetlands function.

This new research suggests that counting acres isn’t enough, and that we’ll have to look more seriously at wetlands’ condition and function if we want to reap the many benefits they provide, including carbon storage, reduced flood risk, and improved water quality. Restoring already-degraded wetlands is still better than not restoring them, but not destroying the ecosystems in the first place looks like the best option of all. Says Moreno-Mateos, “preserve the wetland, don’t degrade the wetland.”