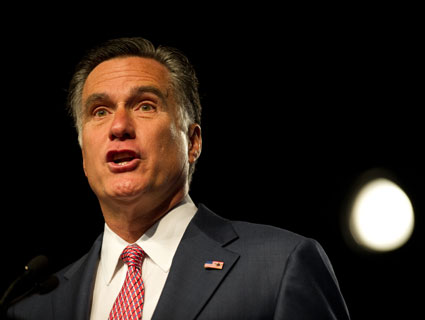

Ana Venegas/The Orange County Register/ZumaPress.com

GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney is in London for the opening ceremonies of the 2012 summer games—part of a three-country world tour designed to build his foreign policy resume and shake down overseas donors. The Romney campaign will run television ads during the games touting the candidate’s experience as CEO of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, where he was widely credited with turning around the scandal-plagued organizing effort.

What Romney doesn’t talk about is how he succeeded in Utah with government help—lots of it—and how millions in assistance that he pried out of the feds ended up bankrolling subsidies, sweetheart deals, and giveaways for land developers and other well-connected Utahns.

As Romney chastises the president for pointing out that successful business ventures benefit from a larger social compact and accuses critics of pining for “free stuff,” Romney is simultaneously touting an Olympic effort that, more than any other in American history, succeeded thanks to public investment—some of it sunk into questionable projects of marginal value to the Salt Lake games. “The $1.5 billion in taxpayer dollars that Congress is pouring into Utah is 1.5 times the amount spent by lawmakers to support all seven Olympic Games held in the U.S. since 1904—combined,” Donald Barlett and James Steele reported for Sports Illustrated in 2001. Those numbers were adjusted for inflation.

How the Salt Lake Games came to receive more money than any games in American history isn’t much of a mystery. The organizers, including Romney, asked for it. In his 2004 book, Turnaround, Romney acknowledges the central role of the federal government in making the Olympics possible. “No matter how well we did cutting costs and raising revenue, we couldn’t have Games without the support of the federal government,” he wrote.

Romney emphasized cost-cutting at every step of the process, moving the Salt Lake Organizing Committee’s DC office from a swank building next door to the White House, to a cheaper, comparatively Spartan flat next to a burrito shop. But the flow of federal cash continued unabated.

In 2000, with the opening ceremonies still more than a year away, Arizona Sen. John McCain called the Salt Lake price tag “a disgrace,” and partnered with Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.) to demand a Government Accountability Office investigation into how the games could cost so much. Romney’s response was muted. As he explained in a letter to the GAO: “Recognizing that our government spends billions of dollars to maintain wartime capability, it is entirely appropriate to invest several hundred millions to promote peace.”

In Turnaround, Romney explained that the Salt Lake Olympics would cost more in large part because winter Olympics tend to cost more, by virtue of the fact that they mostly take place on mountains. “We had to construct access roads, widen highways and overpasses, and build a network of massive park-and-ride lots,” he wrote. Besides, he explained, Atlanta had already upgraded its infrastructure prior to receiving the Olympic bid; Salt Lake City, on the other hand, was still in the process of improving its roads and transit.

But even some of the more maligned projects, like a new light rail system to be built in Salt Lake City, received Romney’s endorsement. Although Romney spends several pages in Turnaround blasting the $326 million project as unnecessary and an example of wasteful “truth stretching” from local governing bodies, he eventually signed on to the Mayor of Salt Lake City’s letter to Congress asking for money to build it.

The most damning aspect of the Salt Lake tab wasn’t the final amount, but how it was being spent. In their exhaustively researched Sports Illustrated accounting, Barlett and Steele explain how many Olympics projects amounted to little more than slush funds for wealthy donors to the games. Wealthy Utahns used the games as an excuse to receive exemptions for projects that would otherwise never meet environmental standards, or to receive generous subsidies for improvements of questionable value to the games—but with serious value to future real estate developments. In one example, a wealthy developer received $3 million to build a three-mile stretch of road through his resort. Where’d he get the money? Federal funds that had been deposited in the Utah Permanent Community Impact Fund. Per the piece:

The U.S. Treasury collects royalties from mining and petroleum companies that prospect and drill on federal lands, and from individuals and businesses that buy and sell the related leases. The Treasury returns half the payments to the states where the lands are located. States generally distribute the money as grants or loans to those communities that have been socially or economically affected by prospecting or drilling. In Utah this money traditionally has gone to struggling counties to help with public needs, like purchasing a fire truck.

Now the state was going to give $2 million in federal royalties to Summit County—by far the state’s richest county, and one in which a majority of the mines closed years ago—and the money would be in the form of an outright grant rather than a loan, even though the fund’s rules state that grants can be made “only when the other financing mechanisms cannot be utilized, where no reasonable method of repayment can be identified, or in emergency situations regarding public health and/or safety.” On top of that the grant was earmarked for construction of a road that would benefit a private developer.

The $3 million resort road wasn’t unique. Snowbasin, the site of the downhill skiing championships in 2002, was one of the more notorious examples of a well-connected Utahn getting a sweetheart deal in the name of the Olympics. Earl Holding, a billionaire oil baron, pressured the Forest Service into giving him title to valuable land in Park Valley in exchange for land of “approximate equal value” elsewhere in the state. But Holding drove a hard bargain; he got Congress to foot the bill for a new—and arguably unnecessary—access road (cost: $15 million), and received more than 10 times the 100 acres that were necessary for the Games. That would allow him to turn what was once protected federal land into a massive, and lucrative, mountain resort.

The government was so instrumental in making the Olympic games happen that Romney created a special award, the “Order of Excellence,” to honor public servants who had helped them pull it off. Among the recipients: John Hoagland, the US Forest Service official responsible for the land transfer of the Snowbasin downhill skiing site.

The government largesse, however, has done little to deter Romney from using the 2002 Olympics as an example of cost-cutting purity. “While I was fighting to save the Olympics, you were fighting to save the Bridge to Nowhere,” Romney told Rick Santorum at a debate in February.

Maybe they weren’t so different after all.