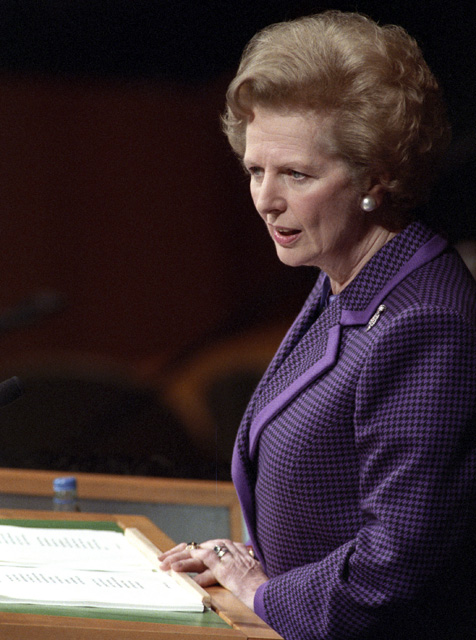

The year: 1990. The venue: Palais des Nations, Geneva. The star: Margaret Thatcher, conservative icon in the final month of her prime ministership. The topic: global warming.

Thatcher went to the Second World Climate Conference to heap praise on the then-infant Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and to sound, again, the alarm over global warming. Not only that, her speech laid out a simple conservative argument for taking environmental action: “It may be cheaper or more cost-effective to take action now,” she said, “than to wait and find we have to pay much more later.” Global warming was, she argued, “real enough for us to make changes and sacrifices, so that we do not live at the expense of future generations.”

The Iron Lady’s speech makes for fascinating reading in the context of 2013’s climate acrimony, drenched as it is in party politics. In the speech, she questioned the very meaning of human progress: booming industrial advances since the Age of Enlightenment could no longer be sustained in the context of environmental damage. We must, she argued, redress the imbalance with nature wrought by development.

“Remember our duty to nature before it is too late,” she warned. “That duty is constant. It is never completed. It lives on as we breathe.”

On climate change, Margaret Thatcher, who died on Monday aged 87, was characteristically steadfast, eloquent, and divisive. “The right always forget this part of her legacy,” Lord Deben, a member of the House of Lords and Chairman of the United Kingdom’s independent Committee on Climate Change, told Climate Desk on Monday. Lord Deben served in the Thatcher government and said she was crucial in raising the profile of climate negotiations around the world, even when it was deeply unpopular amongst her colleagues. “She was determined to take this high-profile position,” he said. “She believed it was her duty as a scientist.” (Thatcher studied science while at Oxford University). Barring a few members, “the rest of the cabinet were not convinced,” he said.

Thatcher also played an instrumental role in bringing the topic to the United States, said Lord Deben. “It was fair to say she got George [H.W.] Bush to go to Rio,” he said of Thatcher’s high-profile entreaties to convince the then-US president to attend climate talks in 1992. “She saw it as her duty to blow the trumpet.”

The Geneva appearance wasn’t her only speech about the need for strong international action. It was something of a theme across the latter years of her leadership. A year before, she shocked the UN General Assembly in New York by issuing a challenge: “The evidence is there. The damage is being done. What do we, the international community, do about it?” The news story in the New York Times ran with the headline: “Thatcher Urges Pact On Climate.” She called for the United Nations to ratify a treaty by…1992.

She also had a domestic plan. Thatcher told British parliament that her government would cut carbon emissions back to 1990 levels by the year 2005. This was met by skepticism by the opposition at the time (female politicians of all eras might be familiar with one such quip from the opposition benches: “The Prime Minister may talk green—she may even dress green—but there are the same old blue policies underneath.”) Lord Deben painted a picture to Climate Desk of cabinet discord over one of Thatcher’s decisions to allow for funds to protect military operations from rising sea levels. “She didn’t convince her Chancellor,” he said.

Thatcher even took denialists to task, telling a Royal Society dinner in March 1990 that the evidence is “undisputed.”

I think that most of us accept this diagnosis yet hardly had I got back when I found that there are researchers who argue—and some were quoted in our newspapers last week—that temperature changes over the last hundred years have less to do with man-made greenhouse effect than with changes in solar activity, something over which we have no control at all.

She thoroughly repudiated this, positing instead a sophisticated understanding of the greenhouse gas effect and the role of CO2 emissions.

But then in 2003, Thatcher, perhaps seeing the conservative tide turning against her climate legacy, watered down the statements she made two decades earlier, calling climate action a “marvelous excuse for supranational socialism,” and accusing Al Gore—who gained worldwide recognition for similar calls for global cooperation—of “apocalyptic hyperbole.” She wrote in her 2003 book Statecraft that “a new dogma about climate change has swept through the left-of-center governing classes.” She praised President George W. Bush for rejecting the Kyoto Protocol, despite her earlier rallying cry for environmental diplomacy. Bob Ward of the Guardian points out that Thatcher’s latter day revisionism is peppered with information from free-market think tanks from the US, “such as the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation.”

Even so, Thatcher is invoked time and time again as someone who used her position to speak passionately about the need for action from the conservative classes. Lord Deben said American politicians should imitate Thatcher’s classic conservative approach to climate change: “You hand on something better to your children than you received yourself. And she was committed to that.”

He warned of the “pure populism” of the American brand of climate denial. “It’s a sort of hillbilly approach to the world,” he said, “[that] I’m afraid is attractive to quite a large portion of the American population.”