<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/home_of_chaos/328141245/sizes/z/in/photolist-uZNXF-uZTsq-87Nub8-ucupp-xJBuk-66ACGo-udjqr-8QpmMc-uddyQ-7wwaH7-5xFuTb-ucdTQ-5xB7KT-uhpHn-aYmvUk-aYmuW8-uZNV5-uZTv2-uZTnv-ucSxi-ucWV1-ucYNR-ucWUM-fN6j6Z-ubagx-udbFz-udjoV-udkYD-uddyS-uddyZ-ucWUQ-ucYNX-ucUfe-ucUfd-ucSxy-ucSxp-uddyU-ucWUX-ud8Cg-ucUfb-ucWUU-ucYNP-uddyX-ucSxu-ucWUW-ucYNQ-ubvjk-ubu7R-uburq-ubv3s-ubvSf/">Abode of Chaos</a>/Flickr

On September 21, 1973, a 24-year-old US citizen named Frank Teruggi Jr. was executed in the National Stadium in Santiago, Chile, one of the first of thousands of victims of General Augusto Pinochet’s murderous 17-year military dictatorship. In the wake of the US-backed coup that cost Frank, and so many others, their lives, I lost my older brother. Forty years after his death, my family is still seeking a modicum of truth and justice for his murder.

The story of Frank’s experience in Chile is not well-known. He was an anti-Vietnam war activist from Chicago—as a student at CalTech, he started an SDS chapter there—who enrolled in the University of Chile in early 1972, drawn by the promise of Salvador Allende’s “peaceful road to socialism.” Along with a group of North American expats that included Charles Horman, the other US citizen killed in the stadium, Frank worked at a small newsletter called FIN (Fuente de Informacion Norteamericano) translating and distributing articles on the activities of the U.S. government and corporations in Chile.

During the last 20 months of his life, he sent letters home every two weeks keeping us up-to-date on his activities, as well as the increasingly dangerous political situation. When some of his letters didn’t arrive, he wrote, presciently: “Perhaps the FBI is intercepting my mail.” In another letter he cautioned, “When you get calls from people wanting my address, tell them you don’t have it. This is just a reasonable precaution in case some agency starts checking up on people in Chile. From what we read in papers down here about Watergate, Nixon’s not above doing anything or spying on anyone.”

Frank actually planned on returning home in the early summer of 1973. But a failed coup attempt in late June set off public demonstrations in support of Allende. During one march, Frank suffered a bullet wound to his ankle that required time for healing. He then decided to stay in Santiago a little longer to help establish an anti-imperialism research center at the University of Chile.

In August, his final letters arrived describing the escalating political instability in Chile. “If we all woke up tomorrow to another attempted coup, few people would be surprised. You get used to the tension, but it makes it very hard to plan my return,” he explained. “It depends on events totally beyond my control (and perhaps imagination).”

But he expressed confidence that being a US citizen would somehow protect him. As he wrote in one of his last letters: “My personal position here is one of relative safety…as a foreigner, I should have little trouble leaving the country if the situation should ever get so bad that it be necessary.”

** ** **

On September 20, nine days after a military junta had seized power, police raided Frank’s group house on Hernan Cortes street and detained him and his American roommate, David Hathaway. They were then taken to the stadium, which Pinochet’s military had transformed into a massive detention, torture, and death camp.

For reasons that remain unclear, David was released the next day; Frank was not. Two days later my brother’s body was delivered to the city morgue bearing signs of torture and gunshot wounds. Among hundreds of other bloodied bodies, he lay there for two weeks while my family frantically contacted the US Embassy to find out where he was and what had happened to him. On October 2, we received the terrible news in a phone call from a friend of Frank’s who had identified his body at the morgue.

Since that day, a 40-year-long pursuit of truth and justice for Frank has taken a dogged route. My father, Frank Sr., then a retired typesetter, was thrust into a role that he was not prepared for, but humbly embraced: to discover the truth about his son’s death. He kept Frank’s cause alive in the press, and, until his own death in 1995, pursued a 22-year-long letter writing campaign seeking answers and accountability.

In February 1974, my father flew to Santiago to find out why his son had been murdered and who had murdered him. He was accompanied by 11 prominent citizens from the Chicago area—including church leaders, politicians, union officials and lawyers. We had hoped his mission to Santiago would bring some clarity, but neither US nor Chilean officials showed any interest in advancing the truth, let alone holding anyone accountable.

“In all honesty I cannot be very optimistic about getting a fuller story at this date and after this lapse of time,” the US Ambassador, David Popper, told the delegation. My father noted that the U.S. government did not seem to be making any major effort to find the truth about Frank: “It is difficult for my family to understand how the US Government can be helping the Government of Chile when they don’t even answer our questions” about a murdered American.

Without any help from the Embassy, at the end of his stay in Chile my father did obtain signed testimony from a fellow prisoner that Frank had been badly tortured and killed at the National Stadium. A Belgian man imprisoned at the stadium, Andre Van Lancker, subsequently came forward to tell us that Frank had been executed by a Chilean officer who used the codename “Alfa-1 or Sigma-1” and that the military had sought to cover up Frank’s presence at the Stadium so as not to have “troubles with the government of the U.S.A.”

The Pinochet regime need not have worried. Although Ambassador Popper promised my father that they would try to “determine the facts” in Frank’s death, the Embassy soon advised the State Department, according to a declassified memorandum, that “they believe further pressure in this regard will be of no avail and merely further exacerbate bilateral relations for no benefit.”

In the name of good relations with the Pinochet regime, the US government assisted a coverup of the circumstances of my brother’s death. A Chilean diplomatic note claimed, falsely, that Frank had been detained for curfew violations on September 20 and released for “lack of merit” the next day. A Chilean intelligence officer informed one US official that he believed “Teruggi was picked up by his [leftist] friends and ultimately disposed of.” The Chilean military officially transmitted to the US government their conclusion that Frank had been associated with “extreme leftist movements” in Chile and involved with some unidentified “organization” that had carried out “a campaign to discredit the Junta del Gobierno.”

My family always wondered how the Chilean military had arrived at this conclusion. Even US State Department officials later asserted that this statement “may have been based on information provided by US intelligence.”

The issue of what role, if any, US intelligence officials who collaborated in the coup might have played in both Frank and Charles Horman’s death remains the key mystery of this tragedy. The Academy Award-winning 1982 movie Missing postulated that Charles had been killed because he had stumbled across information of a covert US role in the coup. Among thousands of US documents on Chile declassified by the Clinton administration in 1999 there is an August 1976 State Department document stating that there was “circumstantial evidence to suggest US intelligence may have played an unfortunate part in Horman’s death”—a conclusion that pertained to Frank’s case as well.

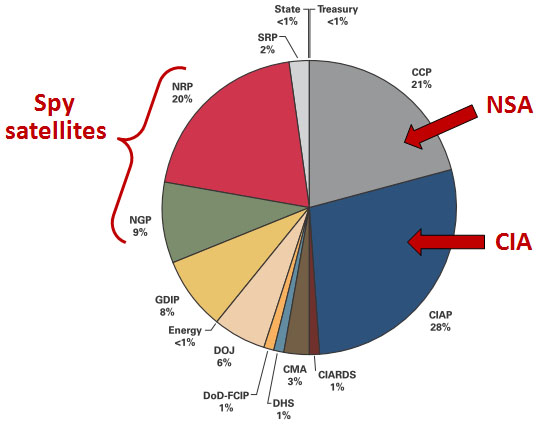

The Clinton administration also declassified a series of FBI reports which revealed that, in fact, the US intelligence community had been monitoring Frank’s mail, and, as he feared, had obtained his address in Chile. In 1972, West German intelligence agents intercepted a letter Frank had sent from Chile to an anti-war dissident living in Heidelberg who was under surveillance; the Germans passed the letter and Frank’s address to the CIA and to a US Army intelligence unit in Munich. The CIA subsequently provided Frank’s address in Santiago to the FBI. The FBI opened a file with documents titled, “Frank Teruggi—Subversive,” on my brother and ordered its Chicago office to begin investigating him. Whether the information they gathered was ever passed to U.S. officials in Chile, and from them to the Chilean military, remains the outstanding question in my brother’s case.

The answer to that question may conceivably be found in the legal investigation conducted in Chile into the murders of Frank and Charles. In December 2000, Joyce Horman initiated a case in the Chilean courts to pursue justice for her murdered husband; our family subsequently joined the case. In November 2011, after more than a decade of investigation, a Chilean judge indicted Col. Pedro Espinoza, a Chilean intelligence officer, along with Capt. Ray E. Davis, the head of US military operations in Chile at the time of the coup.

The indictment, along with the October 2012 authorization of the Chilean Supreme Court to petition the United States for the extradition of Captain Davis, states that he conducted a “secret intelligence-gathering investigation” on US citizens in Chile, and provided the Chilean military with information depicting Frank and Charles as “extremists” and “subversives.” The Chilean Supreme Court’s 500-page extradition request for Ray Davis was only recently delivered to the US consulate in Santiago. There are reports that Davis has Alzheimer’s Disease or may have even passed away recently. We are still awaiting an official US response.

Even if Captain Davis will never answer questions about my brother’s death, the evidence compiled by the judge in Chile may finally provide us with answers surrounding Frank’s murder. My family has waited for four long decades to learn how and why he was killed in the days following the coup. Our ability to accept the unacceptable, and find some semblance of closure, depends on finally knowing.