In his past several budget proposals, House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) has called for big cuts to the federal safety net, especially to the food stamps program. He’d like to see the food assistance program, which helps 46 million people, turned over to the states and reformed the way welfare was in the 1990s, with the imposition of stiff time limits on benefits and work requirements for recipients. But according to a new study, that focus on tying benefits to work has contributed to a major shift in federal welfare spending away from the people who need it most.

Robert Moffitt, an economics professor at Johns Hopkins University, has found that over the past 30 years federal safety net spending has increased dramatically, as Republicans often allege. But that spending hasn’t gone to help the people who need it most. Instead, the additional funding has shifted to help people who aren’t exactly wealthy, but who aren’t doing quite as badly as those at the bottom, largely because they work for some part of the year. The resulting policy shift means that in 2014, a family of four earning $11,925 a year—50 percent of the official poverty line—likely receives less aid than a similar family earning $47,700.

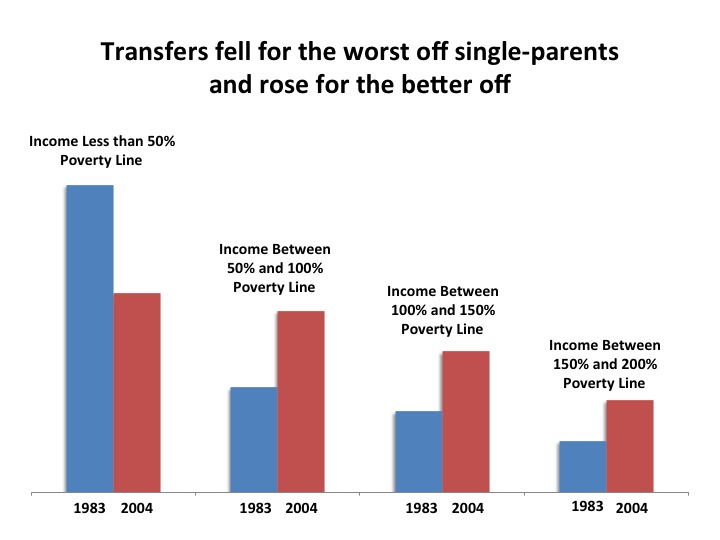

That’s a big change from 1983, when 56 percent of all safety net payments (all major social insurance programs except Medicaid and Medicare) went to families living below 200 percent of the federal poverty line. By 2004, that figure had dropped to 32 percent. Moffitt says the data indicates that even among the poor, inequality is increasing as federal funds have been redistributed from the worst-off families to those doing somewhat better. Federal safety net benefits to single parents living below 50 percent of the poverty line have plummeted 35 percent since 1983.

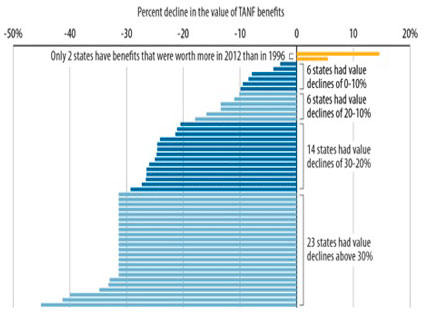

Some demographic groups have fared better than others, namely the elderly and the disabled. Moffitt notes that families headed by someone over the age of 62 have seen their benefits rise by 19 percent over the past 30 years. Meanwhile, those taking the biggest hit are single mothers, who have been disproportionately affected by changes to the welfare system in 1996 that cut off most cash aid to anyone who wasn’t working. Moffitt says the disparity is also the result of large increases in programs that benefit specific groups of low-income people, as the Earned Income Tax Credit does. While the credit lifted more than 3 million children out of poverty in 2012, it’s largest impact is on people who earn at least $10,000 a year or more.

While he doesn’t say it in his presentation, all of these trends are one reason why the number of Americans living on less than $2 a day has doubled since 1996. American politicians’ obsession with helping the “deserving poor” has meant that the people who aren’t so deserving or who are trying and not making it are getting more screwed than ever. “You would think that the government would offer the most support to those who have the lowest incomes and provide less help to those with higher incomes,” Moffitt observed. “But that is not the case.”