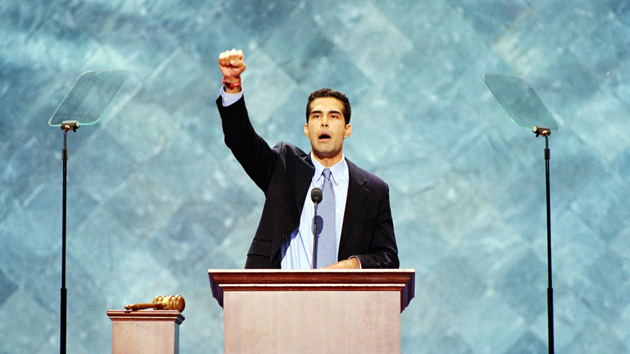

George P. Bush speaks at the 2000 Republican National Convention. Globe Photos/Zuma

George Prescott Bush was campaigning before he knew why. In January, the Fort Worth resident, investor, politico, Navy reservist, and grandson of the 41st president and nephew of the 43rd, announced he was forming an exploratory committee to run for office in Texas. For which office? He didn’t say. Weeks went by, and then finally, in the spring, he tweeted a housekeeping update: He would aim to become the state’s next land commissioner.

But Bushes aren’t groomed from birth to run the General Land Office, even though it is a deceptively powerful agency. Responsible for managing 13 million acres of public land and administering mineral leases, its cachet comes from the fact that almost all of Texas’ public lands are controlled by the state, not the federal government. As such, it provides a natural platform for ambitious politicians. And Bush is ambitious. Already, he is being courted by 2016 presidential candidates, traveling out of state for big speeches, and holding court on the Sunday shows. In a state where Democrats haven’t won a single statewide race since 1994, George P. is a safe bet on next Tuesday’s Election Day.

But what about the many Election Days to come? Bush’s widely expected attempts to follow in the family footsteps (and not just his uncle’s and grandfather’s, but also those of his father, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush) could be derailed by the harsh reality that Texas Republicans have shifted further and further to the right in the 14 years since his uncle ran as a self-described “compassionate conservative.” Two years after replacing Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison with Ted Cruz, Texans are poised to elect a lieutenant governor who believes God speaks to the world through Duck Dynasty and that migrants are sneaking “third-world diseases”—and ISIS—across the border.

George P., a youthful, more moderate voice on the environment and immigration, has endorsed aspects of his relatives’ agendas that are at least as out of favor with the party base as the family brand. He now faces a challenge similar to the one confronting his father as he weighs his own run for president: Can a guy named Bush still make it in Republican politics?

Dynasties have a way of prematurely aging their successive generations, who are thrust into the political process at such a young age. For George P., the rumblings started during his uncle’s first presidential campaign, when he, a 24-year-old teacher, burst on the scene with a primetime address at the 2000 Republican National Convention.

As a campaign surrogate his job was to make his uncle more appealing to young voters and Latinos—George P.’s mother, Columba, was born in Mexico—and not embarrass anyone in the process. Reading contemporary accounts of his work on that campaign feels like unearthing a time capsule from the year the national political press discovered Latinos. Bush was described as “salsa-sexy” (Salon); “a cross between Ricky Martin and John Kennedy Jr.” (USA Today); “a handsome young political warrior with a la vida loca commitment” (Houston Press); “Ricky Martin, except better looking” (a Bush aide granted anonymity by the New York Times); “Rico suave” (ditto); and “the thinking woman’s Ricky Martin” (the Times again).

With no body of work to parse, critics hyperanalyzed his record as an undergraduate at Rice, seizing on a lack of participation in Latino-oriented student organizations as evidence that Bush wasn’t really Hispanic enough. A more substantive criticism was that he didn’t have a lot to say: “Bush sticks to his carefully scripted message and says little else,” reported the Austin Chronicle in August of 2000.

He was only 24, after all. But much of the Texas press would say little has changed since then. Last March, the Dallas Morning News‘ Wayne Slater quipped that the younger Bush was following the “question-avoidance strategy used by his uncle.” In February, the Austin American-Statesman‘s generally liberal editorial board took the unusual step of endorsing Bush’s more conservative primary rival after the Bush campaign failed to respond to nine emails and phone calls requesting an interview. “Bush has a bright future,” wrote Texas Monthly‘s Paul Burka, the dean of Texas political columnists, after the Statesman issued its ruling. “But one has to be skeptical about someone who so far has traded on the family name. Is this all there is?” (The Statesman has endorsed Bush in the general election.)

When he has spoken out, he’s sometimes been cryptic. Take his rhetoric around climate change: Bush accepts that Earth is warming, has called for Texas to take action against Gulf Coast erosion, and has even spoken of wanting to reduce CO2 emissions (though he’s punted on whether CO2 has any impact on climate change). He has also said the United States should move away from coal, while worrying that it would hurt “the Adirondacks.”

But he’s been cautious about the blowback that would come from the base if he fully accepted scientific fact. In August, when a quote published by the Texas Tribune appeared to some to capture Bush as having said that climate change “keeps me up at night,” his campaign pushed back furiously, explaining that climate change doesn’t keep him up at night—hurricanes do. (And, so apparently, does being perceived as a moderate.)

Bush does believe Texas should have a plan for rising sea levels, but he hasn’t said why they’re rising. “There has been changes over the course of time,” he explained in an hourlong public conversation with the Tribune‘s Evan Smith in September, where Bush offered up the fullest available probing of what he actually stands for. “There’s debate over whether or not it’s anthropogenic,” he told Smith. “It’s not my place as an aspiring public servant because I am by no means a scientist or an engineer.”

And on immigration, Bush, who went to Mexico during the 2004 campaign to rally expatriate American voters, has gone out on a limb that Republican candidates rarely return from. He’s called for his party to “return to George W.” and embrace giving legal status to certain undocumented residents while providing in-state college tuition for undocumented alumni of Texas high schools.

That’s a stark contrast to recently elected Texas Republicans like Cruz (who is also considering a run for the White House) and Dan Patrick, the likely incoming lieutenant governor, who considers migration an “invasion.” Attorney General Greg Abbott, who is expected to be the state’s next governor, compared heavily Latino South Texas to a “third-world country” and claimed that undocumented residents had killed 3,000 Texans. The Texas Republican party’s official platform calls for the law granting in-state tuition regardless of graduates’ immigration status to be repealed.

The platform also stipulates that homosexuality is “contrary to the fundamental unchanging truths that have been ordained by God in the Bible” and endorses “reparative therapy” in an attempt to wean gay people away from said lifestyle. On gay rights, and other issues, Bush has struggled to strike a moderate tone. He’s opposed to same-sex marriage “personally,” but seems to recognize the inevitability of it. “[O]n the legal recognition side, we can recognize that as Texans,” he said at the Tribune forum. He’s opposed to the Affordable Care Act, but when asked by Smith about county officials who support Medicaid expansion, he took the fifth: “It’s not a core function of the [General Land Office].” (Neither is abortion, which Bush affirms his opposition to.)

In his interview with Smith, George P.’s most common response when presented with an inconvenient question—on, say, his aunt Laura’s support for marriage equality, or his party’s support for shipping undocumented kids back to Central America, or the alarmingly high number of Latino Texans without health insurance—was to laugh at the awkwardness of being asked about hot-button issues. But at some point, something has to give. George P. Bush can’t laugh away his state’s intraparty divide forever.