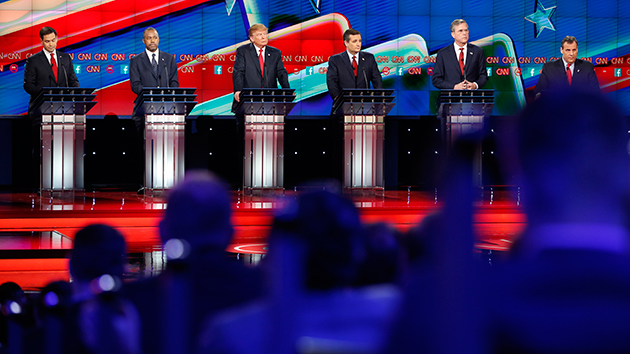

John Locher/AP

For decades—that is, for the entire modern political era—anyone with a dash or two of sense could usually make a reasonable guess about who would win the Republican presidential nomination. It wasn’t tough to pick the winner. The conventional choice—the expected choice—tended to triumph. And it was easy to foresee each cycle how that would transpire. But as the 2016 race enters the pre-voting homestretch, the Republicans have lost their obviousness. History seems to offer no guideline for what is to come. The party of predictability has flown off the rails. The model is broken.

With hindsight, past events often do seem to have a certain inevitability. Yet since World War II and the rise of modern-day, television-shaped politics, the quadrennial GOP contest has often been a rather easy-to-foretell affair. There’s been a series of nomination battles in which the odds-on establishment favorites have won, while the Democrats have endured unpredictable fracases. John Kennedy (1960), George McGovern (1972), Jimmy Carter (1976), Michael Dukakis (1988), Bill Clinton (1992), and Barack Obama (2008)—none of these ultimate big-D winners were the likely victor at the start. In fact, at the outset, they were largely dismissed or disregarded by the party’s pooh-bahs. Democratic insiders of the time, for instance, assumed the Catholic Kennedy could not connect with non-Catholic voters. Each of these Democratic champs was a surprise.

There have been few surprises on the Republican side since Dwight Eisenhower won the GOP nomination in a quasi-brokered convention in 1952. Almost every four years, the obvious candidate or the next-in-line candidate triumphs. Let’s run through the history. In 1960, the next time the prize was up for grabs, Richard Nixon, the sitting vice president (which automatically conveyed upon him next-in-line status), coasted through the primaries with virtually no opposition and snagged the nomination. He then lost a squeaker to Kennedy.

The following presidential election in 1964 was one of the few wild rides for modern-day Republicans. With Nixon on the sidelines, there was a long list of possible GOP contenders, including Govs. Nelson Rockefeller, William Scranton, and George Romney and Sens. Margaret Chase Smith and Barry Goldwater. This led to plenty of pre-primaries scrambling. Rockefeller took a hit when he remarried after having divorced his wife a year earlier. Conservatives rallied around Goldwater; moderate Republicans, then a true power base in the party, feared an electoral wipeout should Goldwater become the nominee. Many of them backed Rockefeller or former Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge. The first primary, held in New Hampshire, was won by Lodge. Goldwater placed second, with Rockefeller close behind. Yet Lodge did a quick fade, and that year, when only 16 states held primaries, Goldwater went on to win far more votes than Rockefeller (38 percent to 22 percent). After a roller-coaster race, the right-wingers had their man, and he went on to be clobbered by Lyndon Johnson, the sitting president.

In 1968, with the GOP in tatters, the guy closest to being next-in-line was the fellow who last had been on a winning national ticket: Nixon. He was back, and the front-runner in the race. He had to brave challenges from Rockefeller, Romney, and a few others. Yet none of his rivals had staying power. Midway through the primaries, Gov. Ronald Reagan of California emerged as Nixon’s most serious challenger. But Nixon rolled past him as well. The safe, establishment-friendly pick was nominated with an overwhelming number of delegates. In the general election, he beat Democrat Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president, who won the unpredictable Democratic contest only after Johnson dropped out and Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Eight years later, in 1976, President Jerry Ford, who replaced the Watergate-scarred Nixon, was the GOP establishment’s choice. But he was not a fully entitled incumbent, having not been elected to the position. And Reagan was back. Still, Ford was the favorite, and Reagan made him sweat. By the time the pair reached the convention, Ford had an edge in delegates but not the majority he needed. Still, due to a last-minute Reagan blunder or two, Ford won on the first ballot. There was no Reagan revolution, but the Gipper had one of the strongest second-place finishes in years. Ford had bested him by only 117 delegates.

After Ford lost to Carter, Reagan held the next-in-line spot. And given that he had nearly toppled an incumbent in 1976, he was clearly the guy to bet on in the 1980 Republican race. There was a field of prominent alternatives: George H.W. Bush, Howard Baker, John Connally, John Anderson, Bob Dole, and others. Yet Reagan trounced his foes in most of the primaries. Bush won a handful of contests—including the Iowa caucuses at the start—but no other candidate claimed any wins. Reagan locked up the nomination long before the primaries were done. Once more, the obvious candidate had conquered.

In subsequent elections, the Republicans stuck to the familiar pattern: The candidate most expected to be the nominee placed first. Bush, after serving as Reagan’s veep, was the 1988 nominee and won the White House. In 1996, Bob Dole, who had come in second in 1988, became the party’s flag carrier against President Bill Clinton. (The last GOP vice president, Dan Quayle, was not really an option—for the obvious reasons—and he opted not to run for president.) In 2000—with no heir apparent remaining from the 1992 and 1996 nomination contests (when commentator Pat Buchanan had each time mounted a fiery insurgent campaign that temporarily interrupted the coronation)—the GOP establishment turned to the next best thing: the son of a former heir apparent. That was George W. Bush, then the governor of Texas.

The Republican power elite showered Bush II with money and support. Though several candidates jumped into the fray, the race turned into a cage match between Bush and Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who was running as a maverick GOPer. It was a dirty campaign. That is, the well-financed Bush forces threw a lot of muck at McCain. (He had been brainwashed as a POW in Vietnam!) McCain depicted himself as a Jedi fighter up against the Death Star. But this was real life, not a movie. The Death Star—the establishment—won. McCain was crushed.

But now he was next in line—which, given the party’s history, was a great spot to be. As the Bush years ended, McCain, once the scourge of the GOP power brokers, made his amends with both party insiders and the conservative wing he had decried during the 2000 race. As the 2008 race began, McCain had the best claim to front-runner status. He did face a handful of competitive challengers: Mitt Romney, Mike Huckabee, Fred Thompson, and Rudy Giuliani. But McCain, after some rough patches, smacked them down, winning 31 states and bagging over 1,500 delegates. Romney and Huckabee essentially tied for second, but far behind, with about 270 delegates each. And we all know what happened four years later in 2012. The 2008 second-place finisher who returned for another shot at it—Romney—also happened to be the establishment favorite, and he ended up smashing a field of extreme and erratic candidates, including Newt Gingrich, Herman Cain, Michelle Bachmann, Rick Perry, and Rick Santorum.

So by and large, over the past 50 years, if you were gaming out the GOP race, you’d identify who was the establishment-approved understudy waiting in the wings (or the closest to that) and—presto!—you’d know who would be the nominee. On the Republican side, this conventional bet has almost always paid off. Goldwater was the only shocker.

Yet as the 2016 campaign approaches the first voting, this model seems to be broken. And it’s not because there are no candidates to play the usual roles. Rick Santorum, the No. 2 in 2012, is trying again, but he has yet to make the adult’s table debate. And for Jeb Bush, the closest thing to an heir apparent surrogate, legacy has so far been a curse. Being a crown prince is not what it used to be.

The GOP’s system is kaput. The Sheep Theory—Republican voters do what the folks in charge want—is no longer operational. According to the polls, the party’s base is entranced by a tycoon outsider who hurls invective and hate. The money and establishment backing that’s undergirding Bush has yet had no impact. And grassroots Republicans, even the conservatives, have forgotten Santorum, as if he were a one-night stand from eons ago. For an observer attempting to plot out what will happen in the months ahead, there is no foundation upon which to render a prediction. Perhaps Jeb(!) will mount a historic comeback and prove that his party remains the party of the hand-picked. But at this stage, you wouldn’t want to bet on that. As for the rest of the field, there is no cause, based on previous experience, to claim that this or that candidate will prevail. The Republicans are in unchartered and roiling waters. All guesses are equal.

The reason for the chaos, though, is obvious. The party elite has become unmoored from the party’s base—and that base has veered further into extreme territory. After years of being fed Obama hatred—death panels, gun-grabs, and secret socialism imported from Kenya by a terrorist-loving covert Muslim!—many die-hard GOP voters are alienated from elected Republicans who haven’t been able to repeal Obamacare, impeach the president, or, better yet, lock him in shackles. Consequently, the wise men of the party can no longer easily direct its voters toward a preferred candidate. At least, not when self-financing, say-anything Donald Trump is in the race, brazenly exploiting the anger and frustration the party’s leaders had previously fueled for their own purposes. So the GOP is in for weeks, if not months, of disorder, in what will likely be a historic break from its usually orderly past. For a party that has encouraged fear and loathing, this is what democracy looks like.