<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&autocomplete_id=&search_tracking_id=L9vRzXJ3VQ4wfHC4rOufaQ&searchterm=breast%20cancer&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=128042738">Fotos593</a>/Shutterstock

Many American women with breast cancer undergo a mastectomy to remove the affected breast, but a growing number are opting to remove the noncancerous breast, too—a surgery known as contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM). A new study in Annals of Surgery suggests that this second procedure, while risky, does nothing to improve a woman’s chances of survival.

In theory, the procedure is intended to prevent breast cancer from developing in the healthy breast—or sometimes to achieve a more symmetrical look after a mastectomy. The number of women doing it has tripled, from just under 4 percent of female breast cancer patients in 2002 to nearly 13 percent in 2012. That’s based on data from nearly 500,000 women, analyzed by researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The procedure is often unnecessary, the researchers noted: Most patients are unlikely to develop cancer in the other breast, unless they have a genetic mutation that makes them particularly susceptible, or have a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. “Our analysis highlights the sustained, sharp rise in popularity of CPM while contributing to the mounting evidence that this more extensive surgery offers no significant survival benefit to women with a first diagnosis of breast cancer,” Dr. Mehra Golshan, a senior author of the study, said in a statement. In addition to the added cost, he noted, having the second surgery prolongs recovery time, increases the risk of complications and the need for repeat surgery, and affects the patient’s “self image.”

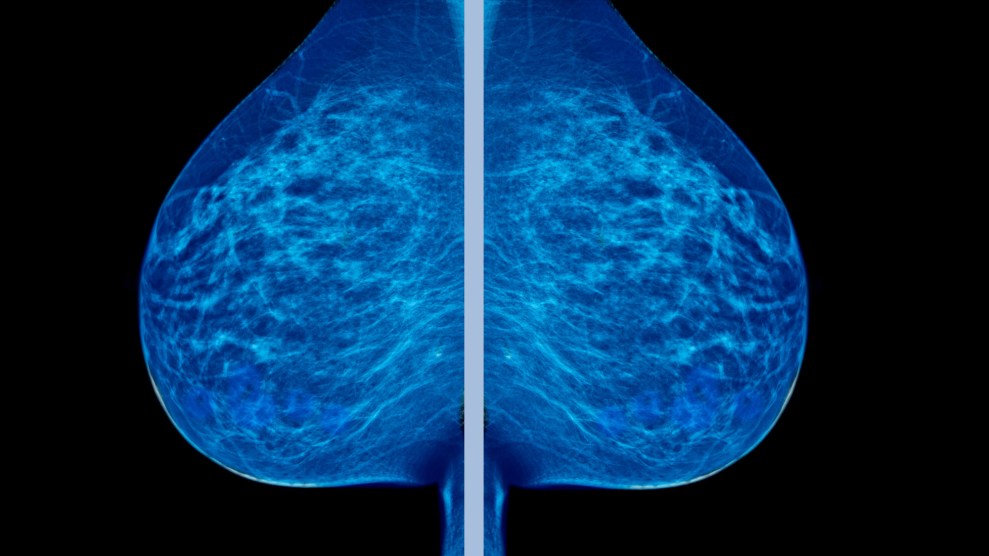

The breast cancer survivor group Susan G. Komen notes one possible cause for the spike in CPMs: MRIs that result in false positives—showing something that looks like cancer but turns out to be benign. Mammograms, too, often result in false positives and have resulted in huge numbers of women getting treatments they don’t need. As Christie Aschwanden pointed out in an investigation for Mother Jones last year:

Mammography isn’t the infallible tool we wanted it to be. Some things that look like cancer on a mammogram (or the biopsy that comes afterward) don’t act like cancer in the body—they don’t invade and proliferate in other organs. Some of the abnormalities breast screenings find will never hurt you, but we don’t yet have the tools to distinguish the harmless ones from the deadly ones. And so these medical tests provoke doctors to categorize lots of merely suspicious cells in with the most dangerous cancers, which means that while some lives are saved, even more women end up with treatments they don’t need…

Mammograms do help a small number of women avoid dying from breast cancer each year, and those lives count, but a 2012 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine calculated that over the last 30 years, mammograms have overdiagnosed 1.3 million women in the United States…Most of the 1.3 million women who were overdiagnosed received some kind of treatment—surgical procedures ranging from lumpectomies to double mastectomies, often with radiation and chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, too—for cancers never destined to bother them.

For more, check out Aschwanden’s full story here.