A Doctors Without Borders employee inside the charred remains of the organization's hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, after it was hit by a US airstrikeNajim Rahim/AP

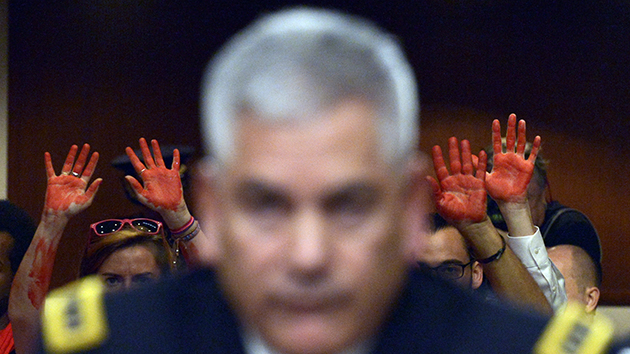

While a United States AC-130 gunship blasted a Médecins Sans Frontières? hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, with howitzer and incendiary rounds early on the morning of October 3, 2015, MSF staff phoned and texted American and Afghan authorities more than a dozen times trying desperately to stop the attack. Medical staff and patients were shot as they fled the building. Others burned to death as they lay in their beds. By the time the half-hour airstrike was over, 42 people—including doctors, nurses, and patients—were dead. The Pentagon later carried out an investigation and determined that while errors were made, no one will face criminal charges.

Though it was horrific, the Kunduz hospital attack was not unusual. It was one of hundreds of assaults on health care workers and hospitals in conflict zones around the globe since 2015, as cataloged in a detailed new report from Johns Hopkins University. The consequences of these attacks have been devastating: In Syria, nearly 30 percent of the health care workers killed in 2015 were executed, shot, or tortured to death. In a single year of war in Yemen, 600 health care facilities, representing a quarter of the country’s health care capacity, were shuttered because of damage or a lack of staff or supplies. Due to what the report describes as the “scorched-earth war” in Sudan, the country’s Upper Nile region is left with only a single hospital to care for 1 million people.

“What really jumped out at me with this report was the sheer geographical scope and pervasiveness of the attacks. It’s so enormous,” says Leonard Rubenstein, who coordinated and edited the report, which also highlights the wider impact of these attacks. “Most of the foreign nurses have left Libya,” says, Rubenstein, a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights and the Berman Institute of Bioethics. “More than 40 percent of the medical staff have left Iraq—just since 2014. It’s not like we’re going back to 2003.”

Attacks on health care workers and medical infrastructure were recorded in 19 countries in just over a year of warfare. The attacks were as varied as they were widespread. In Syria, Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq, and Yemen, hospitals have been struck by aerial bombs. In Democratic Republic of the Congo, seven patients and a nurse were murdered inside a clinic for seemingly no reason at all. In Sudan, when security forces looted a town in West Darfur, civilians were told to take shelter in the local hospital, only to be detained for weeks, during which time the security forces executed at least three people and raped 60 or more women. “ISIL has its own kind of brutality,” says Rubenstein, “expelling patients so that they can have the hospital for their own fighters,” and forcing doctors to treat their wounded under the threat of murder.

As thousands of health care workers have fled conflict zones, few remain with the skills needed to provide basic medical care for the victims of war, not to mention patients suffering from routine yet life-threatening ailments. In just the six most affected conflict areas, the report estimates, more than 40 million people are now left without adequate access to medical care.

There have been virtually no consequences for the perpetrators of these attacks. Regardless of who is committing these atrocities, Rubenstein says, “the law and the norms are being cast aside.” For more than 150 years, international law has deemed these attacks on medical personnel and infrastructure illegal. The Geneva Conventions provide strict rules for warring parties: Attacks must differentiate between military targets and civilian objects, hospitals can’t be taken over for military purposes, and health professionals cannot be punished for providing health care. “A deliberate attack on a health facility is a war crime—it’s true under the Geneva Conventions and the International Criminal Court,” says Rubenstein. When it comes to crimes against health professionals, he says, “There haven’t been prosecutions, and there should be.”